Irish Trailblazers

Wayne Edmonds and Frazier Thompson paved the way for African-American student-athletes at Notre Dame.

By Pete LaFleur

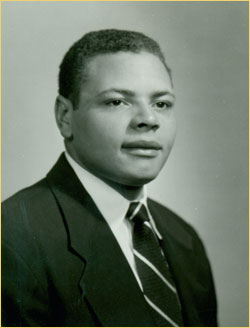

Wayne Edmonds

|

The presenters of the American Flag prior to today’s game are Wayne Edmonds and Paul Thompson. Edmonds in 1953 became one of the first two African-American football players ever to earn a varsity monogram at Notre Dame. Eight years earlier, Frazier Thompson (deceased) – the father of Paul Thompson – earned a monogram as a sprinter on the 1945 Notre Dame track-and-field team. Thompson was the first African-American to be a varsity athlete at Notre Dame, the first to earn a monogram, and the first African-American student ever to graduate from Notre Dame (in 1947)..

To many observers in football-crazed Western Pennsylvania, Wayne Edmonds appeared destined to attend the nearby University of Pittsburgh, which had featured African-American players on its roster since the mid-1940s. Such a hometown hero route for Edmonds was put on hold when he received a call from Bob McBride, then the Notre Dame offensive coordinator and currently still a resident of South Bend.

Shortly thereafter, Edmonds and high school teammate Joe Malone took a visit to Notre Dame late in the spring of 1952. The pair was housed in the modest accommodations of the campus fire house and spent time visiting with four other Pennsylvania natives, each of whom grew up within 10 miles of Edmonds.

“Those guys told us about how much they loved the university and about the hard work that went into being a football player at Notre Dame,” recalls Edmonds, now 74 and residing in Harrisburg, Pa. “Jim and I decided Notre Dame was the place for us.

“I just thought that I’d be more comfortable at Notre Dame and that it would be better for me later in life. It was the best place to showcase my skills and get a good education.”

Notre Dame’s student body in the early 1950s trended to roughly 95 percent Catholic – resulting in a low number of African-Americans on campus at the time. But Edmonds was able to see beyond that challenging ratio and headed off to South Bend, eager to succeed as both a student and athlete.

A handful of African-American players had been members of earlier Notre Dame teams, but Edmonds and running back Dick Washington became the first black players ever to appear in a game for the Irish during their sophomore season of 1953. Each ultimately was awarded a varsity monogram for their contributions to the unbeaten 1953 season (9-0-1), with Edmonds going on to earn two more monograms (including a starting left tackle role in ’55) while Washington enlisted in the Army following the ’53 campaign.

The six-foot, 210-pound Edmonds was a versatile two-way player, able to excel at the tackle, guard and end positions. A bruising blocker on offense and devastating speed rusher on defense, he evoked gushing praise from one writer for being “a veteran smoothie who specializes in smothering quarterbacks as quick as a whistle … with speed and savvy.”

Edmonds and the other African-American players on the team encountered periodic racial issues during road trips to the South, but they faced minimal hardships due to their race when it came to their everyday life as Notre Dame student-athletes.

“I actually experienced more racial issues in high school than I did at Notre Dame,” says Edmonds. “I knew that Frank Leahy had black players on his teams at Boston College. When he came to Notre Dame, he wanted to have blacks, Jews and other minorities on the team. I even roomed in Sorin Hall with a Jewish player on the team, Frank Epstein, and we used to discuss our experiences with minority issues.

“Leahy was the law of the land and nobody questioned him. I had a lot of great teammates at Notre Dame and it was not a situation where you would have to deal with any racial issues.”

Leahy’s firm anti-racial stance was clearly seen early in the 1953 season, when Notre Dame was scheduled to play at Georgia Tech. The Irish were informed that Georgia Tech could not host a team with black players on its roster, but Leahy countered that he would cancel the game if Edmonds and Washington could not play … and a compromise moved the game to Notre Dame Stadium (the Irish won 23-14, for a 4-0 start).

Edmonds spent the younger days of his childhood growing up in McDonald, Pa., before moving with his family to nearby Canonsburg, an area brimming with Polish and Italian immigrants. His father Densel Edmonds was a coal miner who worked nearly 40 years for U.S. Steel, in the Muse Mine and earlier at the McDonald Mine (made famous by Ernie Ford’s “16 Tons” song about “number-9 coal”), before later founding Edmonds Trucking. One of Wayne’s brothers, Densel, Jr., ultimately worked 25 years in the mines while an older brother, Floyd, had been a high school football player in McDonald.

Fortunately for Wayne Edmonds – and for Notre Dame – he followed the lead of his brother Floyd and then some, becoming a four-sport standout at Canonsburg High School (now known as Canon-MacMillan). A three-time letterman in three different sports (football, basketball and track), Edmonds also lettered once in baseball and could have developed into a top catching prospect. His time of 10 seconds in the 100-yard dash held up as the CHS record for nearly 50 years and he captained the football and basketball squads a senior, when he led the Gunners to the 1951 Western Pennsylvania football title.

Edmonds also followed in the footsteps of one of his heroes, Leon Hart, the former Notre Dame end and western-Pa., hero (from Turtle Creek) who won the 1949 Heisman Trophy. “When I went to Notre Dame, I even got to wear Leon Hart’s number 82,” says Edmonds. “He was a player I really looked up to, because he could do it all on offense and defense. I could run well when I caught the ball and my senior year we did not have a kicker, so they had me run in the extra-points and we always scored.”

During his years at Notre Dame, Edmonds became good friends with Joe Bertram (the school’s first African-American basketball player) and later filled a similar role as mentor to Aubrey Lewis, a talented all-around athlete from New Jersey. Lewis – often overlooked among Notre Dame’s “trailblazing” African-American athletes – ended up being a starting halfback on the football team and an All-America hurdler in track-and-field.

“Aubrey was a tremendous physical specimen and could have competed in the Olympic decathlon, if not for injury,” says Edmonds. “I was like a big brother to Aubrey and showed him the ropes, but he went on to do great things as one of the first blacks in the FBI and later a vice president for Woolworth’s.”

Edmonds became socially aware and active during his days at Notre Dame, as a regular reader of the black press. His campus speech about the Emmitt Till case once helped encourage some white Notre Dame students to make donations to the NAACP. Several years after graduating with a degree in sociology, Edmonds was summoned back to Notre Dame – at the request of executive vice president, Rev. Edmund P. Joyce, C.S.C. – to assist in establishing a Black Studies program at his alma mater.

Virtually all of Edmonds’ life after Notre Dame has been geared to helping others. He received his graduate degree from the University of Pittsburgh in the late 1950s before spending five years as a social worker for the Veterans Administration at University Hospital. He was dean of students at Pittsburgh’s School of Social Work, from 1967-71 and then spent several years helping oversee the United Mine Workers healthcare programs in the Midwest. Most recently – for 15 years, prior to his retirement in 1992 – Edmonds worked for the state of Pennsylvania as a public health executive, helping to pattern the state’s programs after the President’s Council for Physical Fitness and Sports.

“My experiences at Notre Dame reinforced things I grew up with – that with hard work and good relationships, you can go a long way,” says Edmonds, whose nephew, Sydney Ribeau, recently was named president of Howard University and considers his uncle Wayne among his most treasured role models.

“Notre Dame gave me an opportunity to see where I had something to give to others.”

Edmonds and his wife Dorothy, who is set to join him in today’s presentation, have four daughters, 11 grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

While the story of Wayne Edmonds has been well-chronicled over the years, Frazier Thompson’s historical significance has been obscured far too long. Such a mysterious story likely is due to a number of factors: Thompson was at Notre Dame in the chaotic late-World War II era; he did not enroll through the conventional process (but rather after being on-campus for a time as a V-12 Navy trainee); he competed in a sport (track) that received minimal publicity or attention; and, later in life, he had limited contact with his two sons after a divorce from their mother when the boys were young.

“My father’s life really is a mystery,” says Paul Thompson, now 58 and two years younger than his brother Frazier, Jr. “We did not have a lot of contact with my father after my parents divorced, so many details of his life still are unknown to us. He would see some of our sport events and things like that, but there’s a lot we don’t know about him.”

The Thompson boys, Paul and Frazier, Jr., lost their mother Clementine in 1983, when her sons still were relatively young men (aged 33 and 35) – thus furthering the absence of details about their father’s life.

“One thing I do know is that my dad loved Notre Dame and cherished his time there,” says Paul. “Notre Dame is the place where he developed his passion for track and he maintained that love for the sport later in his life.

“I can remember as a young boy when my dad took me and my brother to see the 1960 track meet between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R., in Philadelphia. He explained different things to us about the events and that was the day I got to see Ralph Boston long jump and John Thompson high jump. It was a moment when he was able to share his passion for track with us.”

Frazier Leon Thompson, Sr., was born in the mid-1920s in Philadelphia, as one of eight children of Irvin and Pauline Thompson. Two of his brothers served in the Army and his father (known by his middle name, Pritchard) was a rigger in the Philadelphia Navy Yard. The young and eager Frazier was an honors student at John Bertram High School, but he had no formal training as an athlete when he enrolled at Lincoln University in his hometown of Philadelphia.

Shortly thereafter, in the waning months of World War II, Thompson was assigned to the V-12 Navy trainee program at Notre Dame. He ultimately was discharged on Oct. 27, 1944 (following 22 total months of duty), and was encouraged by vice president Father Kenna to return to Notre Dame, in pursuit of his degree.?

Thompson’s academic acumen helped him earn admission into Notre Dame’s undergraduate population and – possibly to help maintain his fitness level – he stumbled upon the track-and-field program, late in the 1945 indoor season. He became a member of Elvin “Doc” Handy’s team and competed that spring, while also pursuing his pre-med studies and holding down a part-time job.

The 5-foot-7, 160-pound Thompson proved to be a quick study in both the classroom and on the track. He posted times of 10 seconds in the 100-yard dash and 22 seconds in the 200. After placing second in the 100- and 200-yard dashes in a 1945 dual meet with Illinois, Thompson had secured enough points to receive his historic monogram. His career highlights included a third-place finish in the 100-yard dash at the Indiana state meet (at Indiana University), helping Notre Dame win the team title. Thompson’s second monogram season, in 1946, included posting a time of 6.2 seconds in the 60-yard dash – but an injury forced him to miss the Central Collegiate Championships held that year at Michigan State.

One year later, Thompson graduated with honors as a member of the Class of 1947. He had become the first African-American ever to graduate from Notre Dame. According to his son Paul, Frazier and Clementine then married in the late 1940s, with Thompson then working initially for the U.S. Postal Service. He later was employed for many years by N.A.S.A., as an engineer involved in the designing of space suits.

“My father worked for N.A.S.A. for a long time, but I’m not really sure what he did after that,” says Paul Thompson. “He was sick in the late-80s and then died in 1991.”

Since 1998, the Black Alumni of Notre Dame has presented a series of scholarships in honor of Frazier Thompson. Some of the recent recipients even have included student-athletes – such as soccer standout Reggie McKnight and football walk-on Matt Mitchell. Four current juniors are the 2008-09 recipients of Frazier Thompson Scholarships: Alvin Adjei (a political science major from Houston), Megan Black (English/theology; Fairfax, Iowa), George Chamberlain (psychology/political science; Charleston, W.Va.) and Kendra Jackson (psychology/computer applications; Dallas).

Notre Dame honored the Thompson family last year in Washington, D.C., recognizing the 60-year anniversary of Frazier Thompson’s graduation from the University. Today, his son, Paul, will help honor his father’s multiple groundbreaking accomplishments by joining Edmonds in presentation of the nation’s colors.

Paul’s older brother, Frazier, Jr., is hoping to attend today’s festivities – as are Paul’s son Andre (12), his grandson Jalen (9, son of Paul’s daughter Anika), and his 18-year-old nephew Brandon (the son of Frazier, Jr.). It will mark the first visit to Notre Dame for the Thompson clan.

“I’m a huge Notre Dame fan and have followed the football team for a number of years,” says Paul Thompson, a prep standout in football, basketball and track. “This will be a thrill and honor for me and my brother. For so many years, we were in the background and now people know that my dad had a family. It will be an emotional time for my father to be recognized like that.”

The list of Paul Thompson’s Notre Dame heroes and favorite moments flow quickly from his memory bank: the famous 10-10 tie with Michigan State in 1966, Alan Page, the ND-USC rivalry, fellow Pennsylvania native Ricky Watters, and Jerome Bettis.

But, as things turn out, Paul Thompson knows that the special nature of today’s celebration lies not in recognizing him and his brother – or even in simply honoring his father. Instead, the most important impact may be on the younger members of their family (Andre, Brandon and Jalen).

“For my son, nephew and grandson, I hope this will be an inspiring experience for them to one day attend Notre Dame as students themselves,” says the proud father/uncle/grandpa.

“My grandson already is talking about going to Notre Dame and playing football, and my son is really into engineering and robotics. I hope that by exposing them to this experience, it will be very inspiring to them as they go forward in life and education.”

Such is the true legacy of Frazier Thompson, Wayne Edmonds and the hundreds of African-American student-athletes who have followed in their footsteps at Notre Dame.