Note: This story originally appeared in the 2018 Stanford issue of Gameday Magazine, the official gameday program of Notre Dame football.

Sitting in North Dining Hall, Luther Bradley felt the rumbling in his stomach. Notre Dame’s freshman defensive back had just eaten a game day breakfast of steak and potatoes. It wasn’t the food that bothered his belly, though. It was the nervousness. In a few hours, the teenager would start in the 1973 season opener for the Fighting Irish. Could he handle this? Was he up for it?

At the dining hall, he had to make a move. He headed to the bathroom. He threw up. Breakfast exited; nervousness stayed. First, he walked back to his dorm room in Fisher Hall. Then he headed over to the stadium.

After warm ups, Bradley sat at his locker. Head coach Ara Parseghian made the rounds in the locker room, stopping to have quick chats with players before the game. He walked over to Bradley.

“How are you feeling?” the coach asked.

Bradley looked up and gave the honest answer. “I’m nervous.”

Parseghian knew what to say and the coach didn’t hesitate in delivering the message Bradley needed to hear.

“If I didn’t believe you could do the job, I would not put you out there. You’ll be fine. Go out there and have fun. You’ll see,” he told Bradley.

Notre Dame pounded Northwestern that day 44-0. Bradley added his own highlight, partially blocking a punt in the second quarter that set up one of Notre Dame’s touchdowns.

Bradley, who would become a first-round draft pick of the Detroit Lions and who still has the most career interceptions in school history, looks back at that brief pregame conversation as a pivotal moment in his career. “That meant the world to me for the rest of my playing days.”

Over the Stanford weekend 57 of Bradley’s teammates were expected to return to campus to celebrate the 45th anniversary of what the team accomplished in 1973. They went undefeated and won the national title. Along the way, they slayed an arch-nemesis, headed south for a battle between iconic coaches and they answered at least one fan’s prayer.

In ’73, the win over Northwestern gave the Irish a 1-0 record, but the season began months earlier. It started right after Notre Dame’s trip to the Orange Bowl. The Nebraska Cornhuskers thrashed the Irish 40-6 on Jan. 1.

“I remember it as the Johnny Rodgers show. He scored touchdowns running, catching and throwing,” said Notre Dame quarterback Tom Clements. “He did some amazing things in that game.”

Johnny Rodgers’ five-touchdown performance came after The Anthony Davis Show at Southern California. Davis scored six touchdowns in USC’s 45-23 win against Notre Dame. Davis’ scores included touchdowns on kickoff returns of 96 and 97-yards. USC went on to win the national title. The loss to the Trojans was the largest margin of defeat for a Parseghian team at Notre Dame until a few weeks later when they played Nebraska.

Add an upset home loss to Missouri to the record and the 1972 Fighting Irish finished 8-3, the worst campaign a Pareghian Notre Dame team would post. After the disaster at the Orange Bowl, Parseghian summoned some stoicism or fortune-telling, or both. He spoke the quote that has become part of Fighting Irish legend. “From these ashes, Notre Dame will rise.”

In the spring, Notre Dame had 20 practices in 30 days. Every Wednesday and Saturday meant full-scale scrimmages, mostly held in Notre Dame Stadium. On the other days, practices included plenty of hitting as the team worked to bury the Orange Bowl loss in the past.

“Guys wanted to do better. It was a very intense physical period,” Clements said.

When the games started, it looked like the Irish might make good on Parseghian’s prediction to rise from the ashes. Notre Dame started the season 5-0. The Irish had allowed only 20 points and they were beating teams by an average of 30 points per game. After Notre Dame beat Army 62-3, players jumped around in the locker room and made more noise than usual. It had very little to do with beating Army. It had everything to do with who the Irish faced next.

The Trojans had become the roadblock to Irish dreams. It predated the Pareghian era. In 1938, USC posted a 13–0 win against top-ranked Notre Dame. In 1948, looking for two consecutive perfect seasons under Frank Leahy, the Fighting Irish had to come back to settle for a 14– 14 tie. In 1964, the year Parseghian came to Notre Dame and resurrected the football program, he took a No. 1-ranked team to USC and lost 20-17 after leading 17-0 at halftime.Luther Bradley

Going into the 1973 showdown the Irish hadn’t beaten USC in six years. The Trojans were the defending national champions and they brought a 23-game unbeaten streak to Notre Dame. It was the sixth-ranked Trojans and eighth-ranked Fighting Irish under the national spotlight on ABC. Bradley remembers game-week excitement blanketing the campus. Parseghian peppered the team with motivational words throughout their practices, Bradley said.

“They’ve got all the accolades,” Parseghian told his team about USC. “They’ve got the Hollywood producers watching their games. They’ve got the pretty cheerleaders. They’ve got the nice weather. But we’ve got a good football team and we’re going to show them who the better team is.”

On the Trojans’ opening play, USC quarterback Pat Haden faked a handoff to Anthony Davis and dropped back to the goal line. With his back to the line of scrimmage, Haden threw a wide receiver screen pass to future Pro Football Hall of Famer Lynn Swann. The way Bradley initially remembered the play is that he read the offense correctly. He slipped past blockers, put a hit on Swann and the pass went incomplete. “All I know is I was out there trying to contribute,” he said.

When he was told how nice and mature that sounds in 2018, Bradley responded with a deep laugh. His laughing continued when Bradley was reminded that he made sure he removed Swann’s helmet on the hit and that as Bradley headed back to the defensive side of the field he shoved Swann for good measure.

“I did. Oh my God, you remember that! I did,” he said through the laughter.

Then the honesty flowed. “I was really geeked out of my mind. All I wanted to do was hit him. Hopefully I could dislodge the ball, but he dropped the ball. Afterward, he gave me a look like, ‘You’re not supposed to hit me.’ I’m like, ‘Hey, I’m just as good as you are.’ So I pushed him. Today I probably would’ve gotten a flag.”

The play set the tone for the game. “It exemplified that we were ready,” said Clements who watched it from the sidelines.

The play that busted the game open came in the third quarter. Notre Dame running back Eric Penick took a handoff at the Irish 15-yard line and went the distance for a Notre Dame touchdown.

“That was probably the loudest I ever heard Notre Dame Stadium,” said Clements, who played for the Irish for three years and coached at the school from 1992 to 1995.

It was redemption for Penick who had been benched during the previous season’s USC game for fumbling twice in the first half. His scoring run put Notre Dame up 20-7. The Irish prevailed 23-14, finally besting their rival.

Notre Dame finished the regular season ranked No. 3. They headed to New Orleans for a Sugar Bowl matchup with No. 1 Alabama. It was the first time the two schools met on the gridiron and it was the first time Alabama head coach Paul “Bear” Bryant and Parseghian faced each other. The game was tinged with cultural battle lines, too. North versus South. Catholics versus Southern Baptists.

In December 2016, during an interview for the forthcoming documentary Hesburgh, Parseghian spoke about an interaction he had the night before the Sugar Bowl.

It was at one of those bowl game social gatherings. As the event died down and the crowd drifted away, Notre Dame President Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, C.S.C. made his way over to the head football coach.

“I was here 11 years and he had never come to me once pre- or postgame with a comment,” Parseghian said.

This night was different.

“You know Ara, I’ve never asked you for anything in the years you’ve been at Notre Dame, but it would please me immensely if you would win tomorrow,”

Why Hesburgh made the statement is unknown. A little more than a year before the game, President Richard Nixon had asked for Hesburgh’s resignation as chair of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission, a position to which Nixon had appointed Hesburgh.

Notre Dame’s president was a founding member of the commission. As part of his work on the commission, Hesburgh presided over public hearings about voting rights issues in Alabama. At the time, a local judge named George Wallace threatened to jail Hesburgh and his fellow commissioners. When Notre Dame played Alabama, Wallace was the state’s governor.

Parseghian didn’t give much thought as to why Hesburgh said what he said. The coach thought more about the fact that the conversation had happened in the first place.

“The world is looking in on this game,” Parseghian said. “And I went to bed that night with more pressure because Fr. Hesburgh had never ever come to me before. … He wanted to win that game. He wanted to compete.”

On game day, back at the team hotel, Luther Bradley started to feel nervous again. It was his first bowl game. The national championship was on the line. Leaving for Tulane Stadium, Bradley met up with Tom Clements at the elevators.

“Tommy, I’m nervous.”

“I’m not nervous. Being nervous is self-inflicted. Just go out there and enjoy this,” the quarterback told the freshman.

That was Clements, “a cool customer,” Bradley said.

For those not old enough to remember, the Sugar Bowl came down to Clements, under pressure, making one of the most important plays in Notre Dame history.

With Notre Dame leading 24-23, Alabama called a timeout with 2:12 left in the game. Notre Dame faced third down and five from its own five-yard line. If Notre Dame could convert the first down, the Irish could run out the game clock and win. If Alabama forced a Notre Dame punt, the Crimson Tide would likely take over a few yards away from a makeable game-winning field goal attempt.

During the timeout, Clements met Parseghian on the sidelines. Alabama figured Notre Dame would play it safe and run the ball. Parseghian told Clements to run “power-I right, tackle trap pass left.” Clements looked at his coach and asked if he was sure. It was the only time Clements double-checked a Parseghian play call.

The Irish lined up with two tight ends tight to the line of scrimmage and three running backs. It’s a formation that screamed running play. Notre Dame went with a long count, hoping to draw Alabama offside. Instead, Notre Dame’s tight end, a future Pro Football Hall of Fame inductee, Dave Casper jumped offside. Now, the Irish were backed up to their own two-and-a-half-yard line. Parseghian didn’t change the play.

Kerry Temple, Notre Dame Magazine editor and a Shreveport, Louisiana, native, was in his senior year at Notre Dame. He watched from the end zone where his Irish were backed up. He started to pray. He prefaced his intentions by telling God he knew the Almighty didn’t really care about, or intervene in, football games. “But if it’s all the same to Him, could Notre Dame please, please, please win this game?”

Temple told God he knew the Southern Baptists in the stadium were praying for the opposite outcome. He made God an offer. If Temple’s prayers were answered, he would never ever pray about a sporting event again.

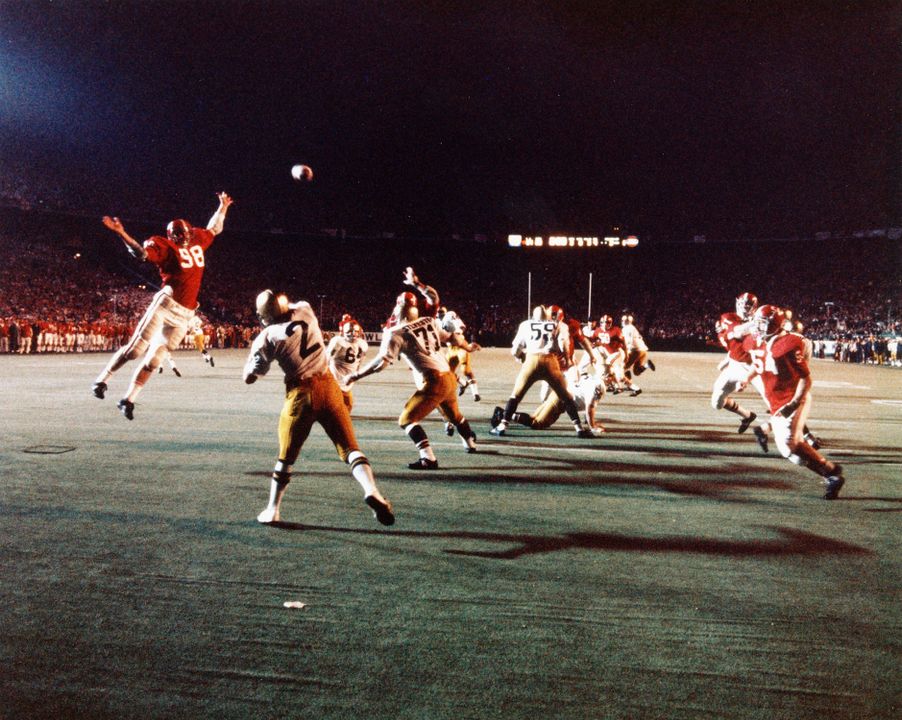

The ball snapped. Clements faked a handoff to Penick. He dropped back into the end zone. In the face of a leaping Alabama defensive lineman on his left side, Clements lofted the ball up the left sideline for a 35-yard completion to tight end Robin Weber.

Notre Dame held on for the win and the national championship. Hesburgh —and all the Irish faithful — must’ve been immensely pleased. And though he has been tempted on a few occasions, Temple has kept his end of the deal, never again praying for sports.

Jerry Barca is a 1999 graduate of Notre Dame. He is a producer and writer on the forthcoming documentary Hesburgh about former Notre Dame President Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, C.S.C.