Sept. 24, 2010

MONOGRAM CLUB CORNER – JOE KERNAN

By Craig Chval

Over the past couple of decades, as politicians, money and 24-hour news channels have unwittingly conspired to provide Americans with a seemingly unending diet of political news, analysis, polls and prognostications, we have seen the evolution of what many have called “the permanent campaign.”

In other words, candidates never stop running for office.

But for Joe Kernan, there was a line that couldn’t be crossed, even in this age of non-stop campaigning. When Kernan was invited by long-time friend and Indiana gubernatorial candidate Frank O’Bannon to run for the office of Indiana lieutenant governor, Kernan extracted one concession from O’Bannon – Kernan would not be campaigning on the days of Notre Dame home football games.

As a life-long resident of South Bend and 1968 graduate of Notre Dame, Kernan wouldn’t be budged.

“That was one of my preconditions,” relates Kernan of his discussions with O’Bannon. “There were six Saturdays when I wasn’t going to be on the campaign trail, I was going to be back home in my seats, watching the Irish.

“I can’t tell you how many people told me how much they admired my uncompromising attitude for those six Saturdays, that the most important thing in the world was not campaigning.”

By the time Kernan was running for statewide office, he had long since developed the ability to put things in perspective.

After graduating from Notre Dame, Kernan served as an officer in the United States Navy. While flying a reconnaissance mission over North Vietnam on May 7, 1972, his plane was shot down. Kernan was able to bail out of the doomed aircraft, but he was captured and held for 11 months in a North Vietnamese prison in Hanoi known as “The Zoo.”

As Kernan tells it with the benefit of hindsight, his plight as a prisoner of war was less horrific than many. By that stage of the war, the North Vietnamese had begun to view U.S. prisoners primarily as bargaining chips in ongoing peace negotiations, rather than as potential sources of intelligence to tortured in the hopes of obtaining useful information.

Despite Kernan’s relatively decent treatment as a prisoner, there were dark days.

The darkest came approximately one month after his capture, when a fellow prisoner informed Kernan that the escort plane which had accompanied Kernan’s plane on its mission had lost contact with Kernan’s plane, leading the Navy – and ultimately Kernan’s family – to presume that he was dead.

Along with his imprisonment, Kernan was left to wrestle with the possibility that neither the Navy nor his family thought he was alive. Imagining his parents, siblings and bride-to-be (Joe and Maggie Kernan were married in 1974) grieving his death added to the burden of being a prisoner.

Communication with the outside world was extremely limited, but eventually, Kernan received confirmation that his family had learned that he had indeed survived being shot down. The confirmation came in a rather unusual way. A package of clothing essentials, thoroughly searched and looted by North Vietnamese prison officials, contained three handkerchiefs with an R-rated, handwritten message from two of Kernan’s Notre Dame classmates, “Wheels” and “Sammy.”

“Wheels” was Bill Kenealy and “Sammy” was Greg Terranova, and not only did their autographed handkerchiefs provide Kernan with a chuckle and a respite from prison-issue tissue paper, but they also signaled that Kernan’s close friends were supporting Kernan’s family through the ordeal.

Once he was assured that his family knew he was alive, it became easier for Kernan to develop a more positive attitude regarding his circumstances.

“To a person, we would all say, `God, we’re the lucky ones,'” he relates, mindful of the fates that had befallen many other POWs. “The first perspective was that you were lucky to be alive. And although we’d much rather be home, aboard our ship, or anyplace else, there was great faith that we were not going to be forgotten and they weren’t leaving (Vietnam) without us.”

Indeed, Kernan and his fellow prisoners were released in the spring of 1973, as the war was ending. Upon his discharge from the Navy, Kernan married Maggie and moved to Cincinnati to work for Procter & Gamble. But it wasn’t long before he returned to South Bend.

“Neither Maggie nor I had jobs, so we didn’t know what we were going to do, but we knew where we were going to live,” he says.

It wasn’t long after the Kernans returned to South Bend that Joe became involved in public service, first as city controller. Then, when two-term mayor Roger Parent decided not to run for re-election in 1987, he persuaded Kernan to throw his hat in the ring. Kernan was elected three times before being elected Indiana’s lieutenant governor in 1996.

“It was the best job I ever had,” says Kernan of his 10 years as South Bend’s mayor.

“What I loved about being mayor is that the things that you’re able to do are much more tangible than perhaps they are at other levels of government,” he explains. “You’re dealing with fundamental services that are the foundation of the quality of life, whether it’s police and fire, or taking care of streets and parks, or water and sewer.”

As much as Kernan enjoyed being mayor, it took an extraordinary circumstance to get him out of the mayor’s office, and out of South Bend. That circumstance occurred leading up to the 1996 Indiana governor’s election, when long-time friend Frank O’Bannon asked Kernan to be his running mate.

“He knew how I felt, that I didn’t want the job, relative to the job I had in South Bend (as mayor),” recalls Kernan. “Since he knew I didn’t really want the job, if he asked me, knowing that, to me that would be a sign that he really needed me.

“He’s a friend and someone who I had great respect for,” Kernan says. “So when I got that phone call, I said I would run, because I felt a responsibility and I felt a duty, both because of my relationship with Governor O’Bannon and because of a belief that there was an opportunity to continue to serve.”

The O’Bannon-Kernan ticket was elected in 2000 and in 2004, before O’Bannon decided not to seek a third term as governor. It was widely expected that Kernan would run to succeed O’Bannon as governor, but Kernan decided to forego the race. O’Bannon suffered a fatal stroke in September 2003, and Kernan became governor. At first, Kernan persisted in his decision not to seek election as governor, but eventually changed his mind. He lost a fiercely contested race against Mitch Daniels in 2004.

As happened so often during his life, both public and private, Kernan’s experience as a POW in Vietnam helped him through the disappointment of that election.

Shortly before making a public concession on election night, Kernan spoke to his family and closest friends.

“Pretty soon, I’m going to have to call my opponent and congratulate him,” Kernan told his inner circle. “And then we’re going to go downstairs with 1,000 people who have been working hard for us for six months, and we’re going to have a party.”

Kernan’s take on the disappointment was pretty simple.

“It’s not the end of the world, there’s nothing you can do to change it, so move on,” he says. “Relish the opportunities we’ve had, and tomorrow is another day, and it will have its own adventure.”

In the midst of the frenzy, Kernan’s youngest brother, Terry, pulled him aside for a private moment. Terry put his arm around his brother and wrapped him in a big bear hug before speaking …

“Does this mean we’re not going to get tickets for the Final Four” asked the kid brother.

“It was perfect,” relates Kernan.

Kernan’s life hasn’t been perfect, but surviving his near-death experience in Vietnam with such a positive perspective set the stage for a remarkable life. Along with his very distinguished career in public service, Kernan was honored by his alma mater with an honorary doctorate in 1998, delivering the commencement address to Notre Dame graduates 30 years after receiving his undergraduate degree.

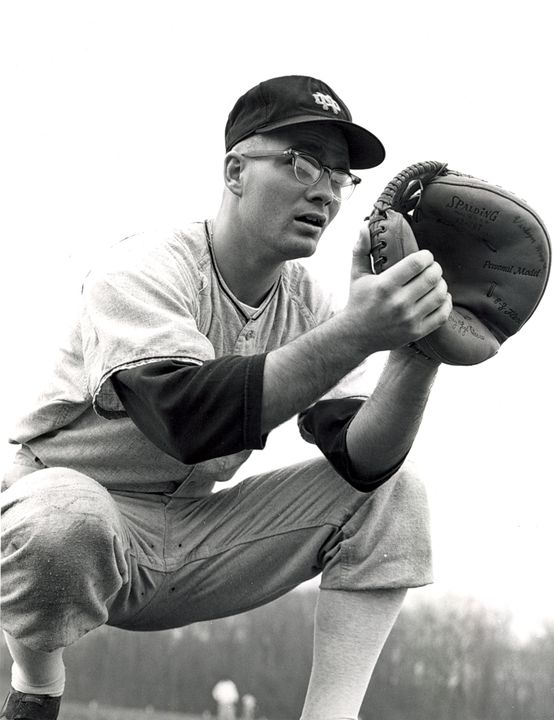

After leaving the governor’s mansion, Kernan led a group of local investors who purchased the Class A South Bend Silverhawks, preventing a sale of out-of-town buyers and preserving professional baseball for South Bend. His role in leading the Silverhawks provides a certain symmetry for Kernan, who starred for Notre Dame’s baseball team in the 1960’s, earning much-needed financial assistance.

As he reflects on the past 40 years, which included a return visit to Vietnam several years ago, on which he was accompanied by both Maggie and “Wheels,” Kernan credits his time as a prisoner with helping him navigate life’s ups and downs.

“I dodged a bullet 38 years ago, and was able to come back home,” he says. “But for the grace of God, I wouldn’t be here, and every day is a new adventure.”

-ND-