Nov. 20, 2014

By Todd Burlage

Based on the written account from Tom Sullivan of his experience in Dallas shortly after the 1970 Cotton Bowl, the trip was more enjoyable than any of the thousands of Irish faithful could have hoped for, save for the 21-17 loss of their beloved team to the mighty squad from the University of Texas.

Sullivan traveled to Dallas as both a fan of the University of Notre Dame and as a representative of the University through his work as managing editor of the Notre Dame Magazine. It proved to be a historic trip considering New Year’s Day 1970 marked the first appearance in a postseason football game for Notre Dame in 45 years. The game also signaled a new and important era for the Irish football program — the official lifting of the “bowl ban.”

“It was a day Notre Dame football fans — and opponents — had anticipated for 45 years,” Sullivan wrote. “The University was abandoning an antiquated custom while at the same time adding immeasurable luster to the game of college football in its centennial year, simply by consenting to participate.”

Looking back today from an era and prism of big business and the mass appeal of college football, it is difficult to understand why Notre Dame chose not to “go bowling” for more than four decades.

But a closer look at the culture of the sport at the time and the procedure with which a national football champion was selected each year helps to clear up Notre Dame’s intentions.

From the time the Associated Press poll began in 1935 through almost all of the 1960s, bowl games were considered mainly glorified exhibition games and postseason rewards for the players because national champions were crowned each year based on the final regular-season rankings and before the bowl games were played.

For example, the 1947 Notre Dame team was declared national champion immediately after the regular season, even though unbeaten and No. 2 Michigan crushed No. 8 USC 49-0 in the Rose Bowl a few weeks later.

Many dismayed Wolverine fans still consider 1947 a title year because an informal survey after the bowl season showed that most AP voters would have changed their No. 1 vote from Notre Dame to Michigan, but the title trophy had already found a home in South Bend. There was no turning back.

The tables were turned in 1953 when the pre-bowl voting process burned Notre Dame, with Maryland declared the national champion over the No. 2 Irish before the bowl season. The Terrapins then lost in the Orange Bowl to Oklahoma — a team Notre Dame had beaten in Norman that season — but, the votes already had been tallied after the regular season so Maryland remained No. 1.

The pendulum swung back in the favor of Notre Dame in 1966 when Ara Parseghian’s 9-0-1 Irish were declared national champions over 11-0 Alabama, even though the Irish didn’t go to a bowl and the No. 3 Crimson Tide put a 34-7 beatdown on No. 6 Nebraska in the Sugar Bowl.

Changing Course

From academic scheduling, to revenue opportunities, to an adjustment in national championship voting, a confluence of factors in 1969 caused the Notre Dame administration under president Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, C.S.C., to lift the bowl ban and allow the Irish to participate in the postseason.

Notre Dame adopted a new academic calendar in 1969, meaning the first semester of school ended in mid-December and didn’t resume until Jan. 5, easing the logistical and travel challenges the previous school calendar placed over student-athletes by keeping them in class until the first semester ended in late January.

In addition to the changes in class scheduling, the lucrative $340,000 payout for an appearance in a major bowl certainly caught the attention of Notre Dame administrators, who agreed any bowl profits would be used to help fund minority scholarships. This educational endeavor was especially important to Father Hesburgh, who had received the Medal of Freedom from U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964 for his work with civil rights legislation.

But perhaps the greatest force of change was that the AP decided in 1968 to begin including bowl results in its final vote to decide a national champion, a game-changer for Notre Dame since it already had cemented its place under Parseghian as one of the top football programs in the country.

“When we decided to go in 1969, we were all novices,” Parseghian says of working through all the logistics for his first bowl game in 20 years as a college head coach. “All precedents were set in 1969. How many players are we going to take? Will the administration and athletic department go, too? What about the wives? I remember being on the phone with other schools on how to do this.”

After seeking some solicited advice on how to handle the massive demands of a bowl trip, Parseghian and the University set strict parameters to help guide any decisions on if and where to accept a bowl bid each year.

There were only 10 bowls in 1969, and Notre Dame wasn’t interested in playing in a second-tier game just for the sake of playing in one. Once the bowl ban was lifted, the goal for the Notre Dame program was to find a place in one of the three major bowls it was eligible for at the time — Orange, Cotton or Sugar — against an opponent that either would give the Irish a chance at a national title or at least boost its standing by playing a higher-ranked opponent.

Remarkably, in six of the nine bowls Notre Dame played between 1969-80 after lifting the postseason ban, its opponent was either unbeaten, ranked No. 1, or both. The Irish won four of those six games.

Parseghian mentions that if all the criteria were met on an opponent and destination, the players were given a “majority wins” vote on whether to accept the bowl bid.

“The precedent had been now set,” Parseghian explains. “If a bowl invitation came up in the future, and our kids wanted to go, and the opposition was a challenge to us, I feel we’d go. We wouldn’t go if we were third-ranked and our opponent was 15th.”

Deep In The Heart

With a 7-1-1 record and one regular-season game still remaining against Air Force, Notre Dame officially ended its 45-year postseason hiatus on Nov. 17, 1969, when it accepted a bid to play in the Cotton Bowl against the Southwest Conference champ — the winner of the game between No. 2 Texas or No. 4 Arkansas.

The Longhorns defeated the Razorbacks 15-14 and jumped to No. 1 in the polls, thus setting up the Cotton Bowl matchup between top-ranked Texas and the No. 9 Irish in the first bowl appearance for Notre Dame since Knute Rockne took his team to Pasadena, California, for the 1924 Rose Bowl.

The first practice for Notre Dame in Dallas was scheduled for Dec. 26, but it was cancelled because winter weather kept flights throughout the East Coast grounded, delaying the arrival of many Irish players who were home for semester break.

As far as the game, the 1970 Cotton Bowl Classic became one for the ages, with Notre Dame quarterback Joe Theisman leading his Irish to an early 10-0 lead and then a 17-14 advantage in the fourth quarter. Texas rallied with a 17-play drive that ended on the game-winning touchdown and a 24-17 Longhorn lead with only 1:06 left in the game.

One of the primary goals, if Notre Dame would even accept a bowl bid, was that the game provided a chance to enhance its ranking in the final poll. Even in the loss to Texas, the Irish did just that after their strong showing in Dallas, climbing to No. 5 in the final AP poll. It was the first time Notre Dame — and perhaps any team at the time — had climbed in the polls after a defeat.

In his written summation for the magazine after his Cotton Bowl experience that year, Sullivan aptly celebrated the trip to Dallas as being an important new beginning for Notre Dame and a worthwhile trip for everybody involved, a postseason event he wisely predicted would set the stage for many more to come.

“Taking all things into consideration,” Sullivan wrote upon his return home, “it might be wise to make tentative reservations down Miami way for Jan. 1, 1971. You just never know.” And indeed, Notre Dame was invited to play No. 3 Nebraska a year later in sunny Miami for the 1971 Orange Bowl.

But on Parseghian’s rather firm “suggestion,” the 9-0 and No. 4 ranked Irish voted that a rematch with top-ranked Texas, and a return trip to Dallas for the Cotton Bowl on New Year’s Day 1971, would serve the program best because of hopes that an upset of the Longhorns would catapult the Irish to the top of the AP ranking and another national championship.

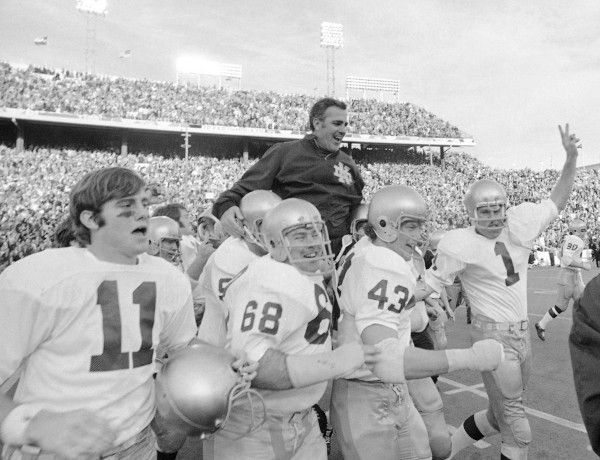

Unfortunately, when Notre Dame lost 38-28 to unranked USC a week after accepting its bowl bid, the Irish dropped to No. 6 in the AP Poll and all national championship hopes were dashed, even after Notre Dame avenged its loss from the previous year and clipped the Longhorns 24-11 in the 1971 Cotton Bowl, ending a 30-game winning streak for Texas.

The Irish fell short of a national championship that year and finished No. 2 in the final AP ranking after that epic upset of the Longhorns, but Notre Dame again accomplished each goal for the trip as a football team and a University family, setting the course for many bowl games to come.

“It was a gatecut (as they say in Texas) ND crowd — the Southerners and the Northerners, the young and the old, those with memories and those with anticipation, the clean-shaven and the hirsute, the liberal and the conservatives …”

It was and continues to be Notre Dame.