Oct. 2, 2014

By Todd Burlage

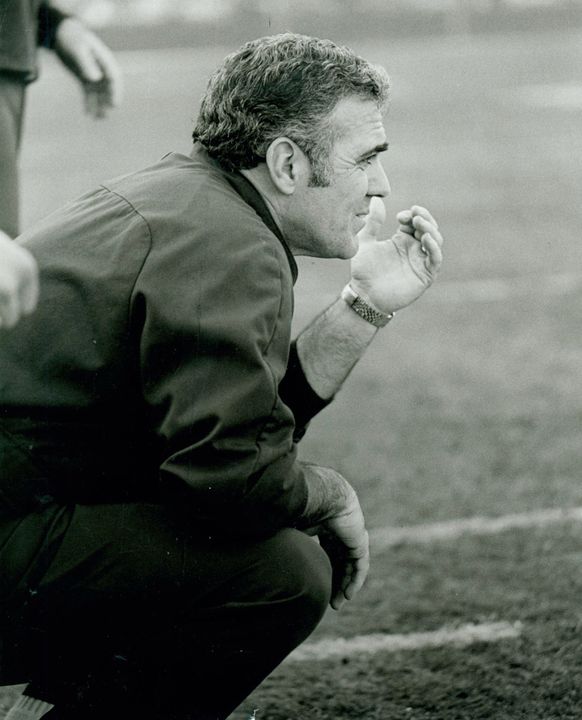

Ara Parseghian uses the word “guarded” when he’s asked to assess his feelings heading into his first season as head football coach at the University of Notre Dame exactly 50 years ago.

Parseghian’s inaugural 1964 campaign produced a 9-1 season and signaled the rebirth of an iconic and once-proud powerhouse football program just one year removed from a 2-7 record that indicated rock bottom.

The legendary Notre Dame coach realized during the 1964 spring season that the talent was in place to pull the Irish football program out of its darkest period in history, but not before he changed the climate and expectations for a team that had developed an acceptance of losing.

Before Parseghian’s arrival, Notre Dame teams from 1956-63 combined for a 34-45 record, including that unthinkable two-win season in 1963 when the Irish averaged 12 points a game and lost their final five contests.

The losing streak included a loss to Navy, a team that the Irish would go on to beat 43 consecutive times beginning in 1964. Prior to that year, Notre Dame had gone five seasons without a winning record and the attitude within the team didn’t leave much hope for a storybook turnaround when Parseghian first arrived on campus.

“Our guys were hungry,” says Parseghian, the guest of honor this weekend for the 50th anniversary reunion of players from his groundbreaking rookie season at Notre Dame. “They knew they were better than what their record had indicated in the past. None of us, however, really knew what to expect.”

Expectations had dropped so low in the 10 years between the exit of legendary Irish coach Frank Leahy — winner of four consensus national championships — and the arrival of Parseghian that a popular theme around campus for the 1964 season was “six and four in ’64.”

“There is an advantage to coming to a program that hasn’t been winning,” Parseghian says. “When you come to a program that hasn’t had success, you have everything to gain and nothing to lose.”

Guarded in his expectations but self-assured as a coach, the brash 40-year-old Parseghian hit the ground running and used his first spring season to instill the necessary discipline, attitude and schematics it takes to become a winning football program.

“Ara simply came in and rebuilt our confidence from day one,” says All-America linebacker Jim Carroll, captain of the 1964 team. “He was such a devoted coach. His great love of the game was contagious. Ara sold us on the fact that we should be confident in ourselves.”

Which, along with improving discipline and getting the right faces in the proper places, were clearly the most important steps to this recovery process.

Coming to Notre Dame after an eight-year stint as head coach at Northwestern, another fine academic institution, Parseghian began his restoration project by preaching schoolwork before football and demanding that his players be model students and gentlemen before athletes.

“That message spread through the team like it was a cancer. Those kids straightened out and flew right,” said the late Mike DeCicco.

DeCicco, a legendary fencing coach at Notre Dame and former academic advisor for the football team, remained one of Parseghian’s closest friends and confidants up until his death.

“Ara told us he respected what Notre Dame meant on the academic side even more than athletically,” DeCicco said. “Everyone thinks coaches always are looking for ways to beat the system, but that was not Ara’s way of doing things.

“He told those kids they had to follow the academic guidelines that were outlined or they wouldn’t play. And the first kid who stepped on the cracks, Ara booted him off the field. There was complete discipline.”

Players who tested their new coach found out hard and fast that wasn’t a good idea.

“It happened to a guy on the team, probably our best pro prospect, and he was kicked off the team,” says Brian Boulac, a standout player for the Irish in the early 1960s and a graduate assistant coach under Parseghian. “Kids saw that the man meant what he said. He stood by his guns.”

Former Notre Dame tailback Jim Morse, a team captain in 1956, was working as the voice of Notre Dame football for ABC Radio when Parseghian arrived in South Bend. Morse remembers that Parseghian’s strong personality sent a clear message that a transformation was going to take place … immediately.

“He was as intense, or more so, than any guy I have ever met. He was ready to go from day one,” Morse says. “He was organized and dedicated. Everything you would look for in a football coach I think Ara had. I was very impressed with him from the moment we first met. There was a purpose to everything that he did. There was never any wasted time in practice or in preparation.”

Where To Begin?

Parseghian recognized almost immediately he had enough front-line talent to win and win immediately. His primary concerns during his first spring season were improving morale, getting the best players on the field and finding the right positions for those players.

The previous coaching staff seemingly showed little patience with the players, Parseghian recalls, creating a climate of self-doubt and a counterproductive fear of failure.

“What was happening, the guys would go into the game, have three plays, maybe make a mistake and they would jerk him out of the game,” Parseghian says. “They never apparently gave their guys an opportunity to show what they were capable of doing.”

Make no mistake, Parseghian was a stern disciplinarian who demanded attention to detail and didn’t tolerate careless mistakes. But by putting his faith in his own players, they then began to put faith in themselves, and the positive results quickly showed.

“Notre Dame guys are smart guys. They can sense when you don’t believe in them and that is what was happening,” Parseghian says. “If the coach doesn’t believe in his players, then what do you have? You can’t be successful that way. It starts at the top.”

Before Parseghian could begin evaluating and organizing his players for the 1964 season, he first had to build a coaching staff to teach and guide them.

Parseghian’s plan was to bring in a few assistants he had grown familiar and comfortable with from his previous two coaching stops at Miami of Ohio (1951-’55) and Northwestern (1956-’63) and blend them with former Irish players and a group of holdovers from the previous Notre Dame staff to help ease the transition.

The late Tom Pagna, who played for Parseghian at Miami of Ohio, joined the Irish staff from Northwestern along with Richard “Doc” Urich and Paul Shoults because of their familiarity from previously coaching together.

“Ara told his assistants, `Loyalty is a two-way street’ and there was great mutual respect among all of us,” Pagna said. “He was a dynamic personality and commanded your attention. If you had an idea, he heard it out and he might make it better. As a member of that staff, you wanted to be a contributor.”

The other five assistants on Parseghian’s first staff all were former Notre Dame players and/or Irish assistant coaches from the 1963 staff working under interim coach Hugh Devore. That group included South Bend native Johnny Ray who previously had served five years as the head coach at John Carroll University and Joe Yonto, head coach at Notre Dame High School in Niles, Illinois. Parseghian’s three other coaching hires — Dave Hurd, George Sefcik and John Murphy — all were retained from Devore’s staff.

“Ara did a great job of balancing that staff and we worked well together as a team of coaches,” Pagna said. “It was a very strong staff from the top down.”

With his staff in place, getting players organized through an overhaul of his starting lineup proved to be the next order of business and arguably the most important responsibility to making the program well again. Parseghian’s gift for talent recognition and position placement is what separated him from his predecessors at Notre Dame.

Where the previous staff seldom played an elusive quarterback named John Huarte, Parseghian decided during the spring season that Huarte would be his opening-day starter in the fall. Under-appreciated and underutilized by the previous staff, Huarte logged only 50 minutes of total playing time during his sophomore and junior seasons and never even earned a varsity monogram.

“Ara was very smart in how he handled the players,” Huarte says. “In my case, he told me just to go out there and play and if I made mistakes they were going to stick with me. He also was very good at using players in the scope of their skill levels. Developing his offensive scheme to maximize the personnel served as one of his biggest strengths.”

The rest, as they say, is history.

Huarte parlayed his starting gig and the faith of a new coach into first-team All-America honors and a Heisman Trophy in 1964 as the best college football player in the country. That’s not bad for a seldom-used backup the previous two seasons.

“To have that happen is very dramatic as I look back on it now,” Parseghian says of Huarte’s rise to stardom. “I don’t think you will ever see that circumstance again.”

Helping Huarte’s rise from sub to star was Parseghian’s vision to move fellow senior Jack Snow from fullback to wide receiver. Snow dropped 15 pounds and became Huarte’s favorite target, setting several Notre Dame single-game and season receiving records on his way to a fifth-place finish in the Heisman Trophy balloting, just two spots behind legendary Illinois linebacker Dick Butkus.

But Parseghian wasn’t finished with his lineup shuffling. In the hope of moving from the ground-and-pound style of the previous years to a faster-paced offensive system that would better utilize the forward pass, Parseghian ditched the “Elephant Backfield” scheme that featured beefy backs Paul Costa (240 pounds), Jim Snowden (250 pounds) and Pete Duranko (235 pounds) and transformed all three players into terrific linemen. Duranko became an All-American at defensive end and an anchor to the defense on the 1966 national championship team.

“Ara inherited a lot of good football players who had come to Notre Dame for one reason or another,” Morse says. “They bought into the program right away because they were good athletes and there was just a whole new aura about the program. [Parseghian] was here to win football games and whatever it took to do that within the rules, that’s what they were going to do. And if you didn’t like the program, then you didn’t want to be around here.”

Up until Ara’s arrival in 1964, college rules required players to play both offense and defense, and any player that was taken out of the game couldn’t return. A new two-platoon rule adopted for that season gave Parseghian the flexibility to situate his players at their best positions, rather than trying to teach them both offense and defense. Huarte and Snow could concentrate only on offense while standouts such as defensive lineman Alan Page and linebacker Jim Lynch developed their skills as two of the best defensive players ever to line up at Notre Dame.

“[Parseghian] could adjust to the situation and put people in the right positions,” Morse says. “He led virtually the same players from a 2-7 season [in 1963] to a 9-1 record the next year.”

The First Test

With his units in place and a new confidence simmering within the program through spring ball and fall training camp, Parseghian and his Irish got their first test with a season-opening game at Camp Randall Stadium in Madison, Wisconsin against perennial football power Wisconsin.

Two years removed from an appearance in the Rose Bowl and a No. 2 ranking in the final Associated Press poll, the Badgers had beaten Notre Dame the two previous seasons and nothing suggested 1964 would end any differently.

“We didn’t know what to expect,” Parseghian says. “We felt like we had made the necessary changes to be competitive, but there is no way of knowing for sure until you finally get out there and play a game.”

One game does not a season nor a turnaround make, but when the Irish left Wisconsin with a shocking 31-7 upset of the Badgers, everything in and around the Notre Dame program began to change. The Irish jumped from unranked to No. 9 in the AP poll after the victory, and the players went from hoping to win to expecting to win. Even the success-starved fans began taking notice and threw their full support at the roots of this resurgence.

The momentum didn’t stop with Wisconsin. It only started. When the team returned to campus by bus from Madison around midnight, Irish fans had lined the streets around campus to celebrate the landmark win that truly marked the dawn of the Parseghian era.

“People started to come out to practice, it was remarkable,” Parseghian says. “The students and faculty would be lined up on the sidelines. They would be there and we would be rehearsing our reverses and special plays and they would `ooh and aah.’ They were really into it.”

Following the victory over Wisconsin, Parseghian’s Irish rolled to easy wins over Purdue, Air Force, UCLA, Stanford and Navy in consecutive weeks to become the No. 1-ranked team in the country for the first time in 10 years.

“As soon as our players experienced a little success, I saw exhilaration overtake them, the feeling that they could get the job done and how something dramatic was in the making,” Parseghian says of the quick climate change. “We got the engine going and got the momentum.”

The attention was everywhere. Parseghian and Huarte graced the covers of Time and Sports Illustrated in 1964, drawing headlines such as “The Fighting Irish Fight Again” and “Notre Dame Returns To Power.”

“With all the tradition, you can imagine how hungry our students have been during these lean years,” is how former Notre Dame athletic director Ed “Moose” Krause summed up the fan support and excitement during the 1964 season.

“They know the history but they’ve had nothing to yell about. It’s easy to see why the fever has gripped them, and why Ara’s enthusiasm got them from the beginning.”

A 17-15 win against Pittsburgh turned out to be the only real scare for the Irish en route to their 9-0 start. Notre Dame dismantled its other eight opponents by a combined score of 253-42, setting up a season-finale at USC with a perfect season and a consensus national championship on the line for Notre Dame.

The Irish fell short against the Trojans, losing 20-17 in the closing seconds to settle for a No. 3 ranking in the final AP poll that season. But the loss to USC seemed to be only a temporary setback and the 1964 season became a launch point to an 11-year career at Notre Dame that saw Parseghian go 95-17-4 with two consensus national championships (1966 and 1973), earning him the lasting title as the savior of Notre Dame football.

In his book titled “Era of Ara,” Pagna recalls how a football program and fanbase were starving for a return to glory and “Ara provided the transfusion.”

And now, 50 years later, members of that unforgettable team have gathered this weekend to celebrate their 91-year-old coach and reminisce about the magical season that truly woke up the echoes after the darkest period in the history of Irish football.

“All the runs will be longer. All the tackles will be harder. All the passes caught will be longer that what the facts actually are. But it will be a lot of fun seeing everybody since they are all grown,” says Parseghian, almost in disbelief that 50 years have passed so quickly. “I used to preach to these kids when they were out there that this is going to be only for four years and then you are going to have a family and a job.

“I told them this time would be the culmination of their lives from when they were 18 to 22 years old before meeting the challenges that our lives give us. That’s what Notre Dame is all about. That’s what I remember most.”