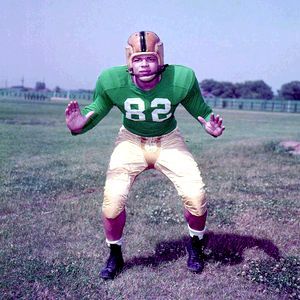

Wayne Edmonds: Breaking Barriers

By Wayne Edmonds '56Wayne Edmonds came to Notre Dame in autumn 1952 from the western Pennsylvania coal town of Canonsburg. He became the first Black player to earn a Monogram in football. He majored in sociology and, after graduation, went on to earn a master’s degree in social work at the University of Pittsburgh. He had a long and highly successful career in social work, education, and physical fitness.

This installment of Signed, the Irish is part of a yearlong celebration in honor of Thompson’s legacy and the extraordinary contributions by our Black student-athletes.

By the time I reached senior year of high school in autumn 1951, I had attracted the attention of several college football programs. I visited Penn State, Penn, and Colgate, but I really expected to go to the University of Pittsburgh, where I had the promise of a full scholarship and a commitment for graduate school if I wanted to go. (I had even been contacted by the University of Georgia, which obviously didn’t realize I was Black. What a visit that could have turned into!)

Then, thanks to scouting reports and information from Notre Dame supporters in western Pennsylvania, I got a call from Coach Bob McBride, an assistant to head coach Frank Leahy, at Notre Dame. He invited me to visit. And so, on a lark, I went with my Canonsburg High School teammate Jim Malone to South Bend.

I knew Notre Dame had never before had a Black football player, but I was impressed by the campus and the academic program. And I knew Coach Frank Leahy had had Black players on his team at Boston College and so would probably be open to minority players now that he was coaching at Notre Dame.

In the end, the biggest hurdle to my going to Notre Dame was my mother, Grace Edmonds, who was afraid Notre Dame would turn her Baptist son into a Catholic. Coach McBride promised that he would see that I got to Baptist services every Sunday, and that was good enough for Mom.

In fall 1952, I set out to Notre Dame—again with my teammate Jim Malone. My Notre Dame years were full of difficult challenges and unforgettable experiences. Joining me on the football team in autumn 1952 was another young Black man from western Pennsylvania, Dick Washington.

Freshmen weren’t allowed to play in those days—we were to concentrate on our studies. Dick washed out during sophomore year, so I became the first Black player to remain at Notre Dame long enough to earn a monogram in football.

With the support of the Notre Dame athletic department and the administration, I made desegregation of the football team a reality and set the pace for other young Black men who wanted to come to South Bend to play.

I went to Notre Dame as an end but was moved to tackle in my sophomore year. I achieved monogram status three years, including with the 1953 national championship team.

In 1953, Notre Dame’s season-opener was at Oklahoma. No hotel could be found in Norman that would accommodate the entire team— Black players and white—so we stayed at a hotel an hour or so outside the university town. On game day, as the team buses drove to the stadium, Coach Leahy used that fact to whip up the players’ enthusiasm to beat Oklahoma, which we did by a score of 28–21.

The 1953 Notre Dame–North Carolina game also was memorable; not because it was a close game, but because Dick Washington and I were the first Blacks to appear in Kenan Stadium in Chapel Hill. The Black fans, seated in a segregated section of the stands, roared as the two young Black men ran onto the field with the Notre Dame team.

Still later in the 1953 season, Notre Dame was to play Georgia Tech, which had a thirty-one-game winning streak and the number one ranking at the time. It was to be a home game for Georgia Tech, but Tech said Notre Dame couldn’t bring me or Dick Washington onto the field in Atlanta.

Our Lady stood strong. If Georgia Tech wanted to play Notre Dame, Frank Leahy said, it would have to come to South Bend and play the entire Notre Dame team. They came. Notre Dame won, 27–14.

After the 1955 game with the Miami Hurricanes, in a special exception to the sanctity of the Notre Dame locker room, Jake Gaither, the legendary coach of Florida A&M University, came in, got me, and took me with him for a celebration of the Notre Dame victory in the Miami Black community.

The experience was like something out of Cabin in the Sky—I enjoyed the music and the adoring fans, signing autographs and getting back to the hotel in Miami in the wee hours of the morning. I never knew who engineered that experience, but figured it had been arranged by Coach Leahy or Father Ted Hesburgh, both of whom looked out for me while I was at Notre Dame. Nobody, even Jake Gaither, gets into the locker room without someone higher up approving.

Off the football field there were ups and downs. I recall walking back to campus one day with another Black student when one of the Notre Dame priests, known as Father Mac, stopped his car and told us we were in a “restricted” part of town where Notre Dame students weren’t supposed to be. (In other words, we were in the Black section of town.) I replied, “We went to get a haircut—you know the campus barbershop only cuts white hair.” That got us off the hook with Father Mac, but the Notre Dame barbershop did not change its discriminatory policy for many years after that.

In the 1954–55 academic year, I had the privilege of living in Sorin Hall in the room that had been occupied in the 1920s by Harry Stuhldreher of “Four Horsemen” fame. One afternoon, while visiting his son who was then at Notre Dame, Stuhldreher showed up to look at his old room. I had the chance to meet and talk with him a bit, an amazing experience for any Notre Dame football player. What a thrill!

In that same hall that year, there was a fire one Saturday caused by a sunlamp that had been left on. I was in the dorm at the time and helped those in the hall to get out. Among those I helped was a “don,” a residential advisor, who lived in the hall. This don was a professor who had flunked me in an English literature course the prior year.

When I complained to the athletic department, they said that, if they had known, they would have warned me not to take that professor’s course because he was known not to like football players. After I “rescued” the don from the dorm fire, he asked me to take his course again. I did so and got an acceptable, accurate grade. And maybe the don’s prejudice against football players ended. One could only hope!

When I came back to campus in autumn 1955, I was disturbed, as was most of America, about the murder in Mississippi of Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old Black boy from Chicago. But I heard no discussion of the atrocity in class or anywhere on campus. As it happened, I was taking a speech course that semester and I decided to do a speech on the Emmett Till murder.

I enlisted a couple of classmates to raise their hands and hold up dollar bills when I came to the part of the speech where I would ask for donations to help achieve some justice in this awful situation. I ended up getting the then-enormous sum of fifty dollars.

I was prepared to refund it to the donors, but the professor said, “No, you need to see that the NAACP gets the money.” I had no idea how to do that, but I had a friend and mentor in South Bend, Art Hurd, a labor organizer and business owner, and I knew he would know what to do.

That was how I first got involved with the NAACP. I remained involved throughout my adult life, eventually serving as chair of the Canonsburg chapter. (As an aside, at a class reunion many years after the Till murder, several of my classmates told me their parents had selected Notre Dame for them partly because it would be a safe place for them during the coming civil rights upheaval. So they were shocked when I walked into the classroom on the first day.)

My father and my brother had been to the campus for a few games, but my mother had never visited Notre Dame until my graduation in 1956. I graduated from the College of Arts and Letters. My major was sociology, supplemented with courses in my other interests—history, English, and philosophy.

Since my earliest years in the Number Nine coal patch and the little town of McDonald, Pennsylvania, my ambition had been to become a social worker. I had seen how social service agency staff treated the people they visited. I vowed I would do things differently.

During Christmas my senior year, I wrote to the dean of the School of Social Work at the University of Pittsburgh, inquiring about entering the MSW program in the fall of 1956.

Those plans took a brief detour as inquiries came in from professional football teams, including the Green Bay Packers, the Philadelphia Eagles, the Chicago Bears, and my hometown team, the Pittsburgh Steelers. I was the second of eight players from the 1956 Notre Dame team to be drafted, taken by the Steelers in the ninth round.

I was the first lineman to receive a signing bonus from the Steelers, the handsome sum of $500. But while at the Steelers’ training camp, my dad brought me a letter from Pitt, admitting me to the School of Social Work.

So I left training camp and set about to begin my career in social work. And what a career it was! Fittingly for a child from the coal fields, I spent a substantial part of it working with and for the United Mine Workers, administering health and benefit programs.

I worked in academia, as a professor and a dean at Pitt’s School of Social Work and at California State University in California, Pennsylvania. And eventually I found my way into physical fitness, administering at the state level programs for youth, senior citizens, and disabled Pennsylvanians.

In December 1991 I retired or, as I like to say, “graduated” to tend my garden, enjoy the company of my wife and my four daughters, ten grandchildren, and nine great grandchildren—so far.

In 2009, when the Notre Dame athletic department celebrated “60 Years of Success by Black Athletes” at the university, I had the honor of presenting the flag in pre-game ceremonies before the ND–San Diego State season opener.

I did so alongside one of the sons of Frazier Thompson, who earned the first monogram by a Black athlete in 1947 in track. My experiences at Notre Dame reinforced values I grew up with— that with hard work and good relationships, you can go a long way.

Notre Dame gave me an opportunity to see where I had something to give to others.