Tommy Hawkins: A Sense of Belonging

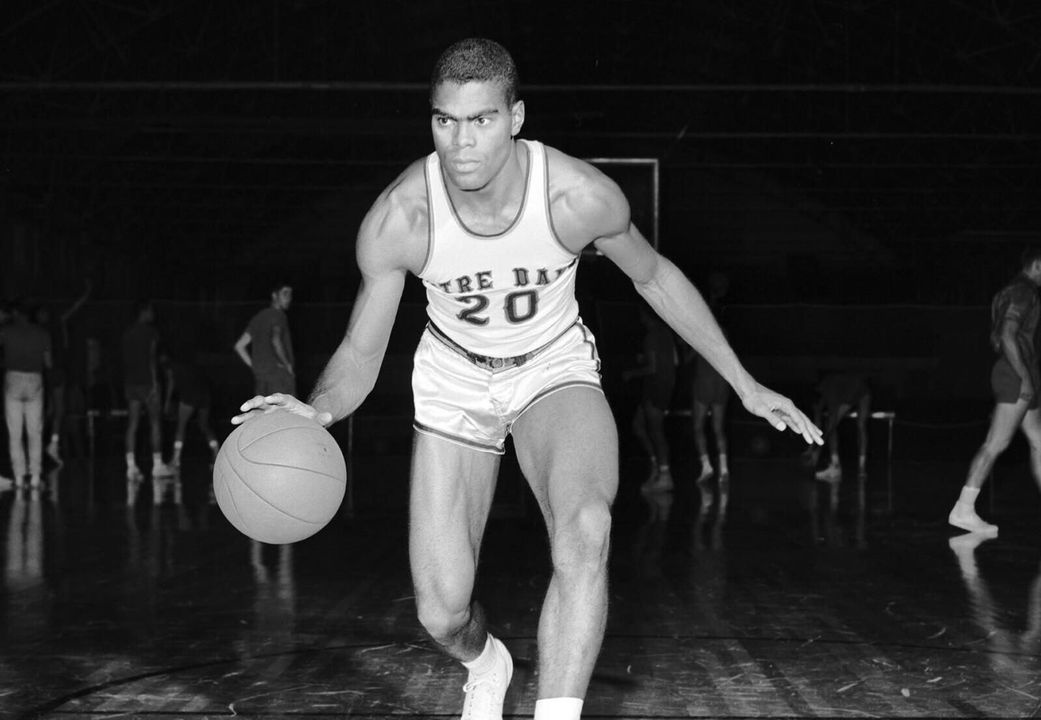

By Tommy Hawkins '59Tommy Hawkins came to Notre Dame in autumn 1955 from Chicago. He majored in sociology and was the Irish’s first Black basketball All-American. After graduation he spent ten productive years in the NBA—six with the Lakers and four with the old Cincinnati Royals. He later was a television and radio broadcaster. He spent the last eighteen years of his career as vice president of communications for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Hawkins passed away in 2017.

This installment of Signed, the Irish is part of a yearlong celebration in honor of Thompson’s legacy and the extraordinary contributions by our Black student-athletes.

Back in 1955, I was one of two Black students in our freshman class of 1,200. At that time, there were only ten Blacks attending the all-male university. Please keep in mind, this was before President Barack Obama was born and before Rosa Parks’ and Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Montgomery bus boycott.

My matriculation at “the Dome” preceded by nine years the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964. It followed by just one year the US Supreme Court’s unanimous ruling in Brown v. Board of Education outlawing segregation in public schools.

Despite that ruling, integration was by no means the law of the land; for the most part, segregation ruled. Having grown up in Chicago, just ninety miles west of South Bend, the spectacle of the Fighting Irish of Notre Dame always loomed brilliantly before me.

However, I never thought that one day I would become a part of the great Irish tradition. In deciding to accept a four-year scholarship to Notre Dame, considerations of race and religion were not factors.

I had already experienced four years of first-time integration (1951–55) at Parker High School in Chicago, where I served my school as a racial ambassador, mediating student racial conflicts. At the same time, I led all basketball players in the city in scoring my senior year and was named Chicago’s most valuable player.

At good ol’ Parker High, I was coached by the gregarious Irish Catholic Eddy O’Farrell, who had grown up in the Windy City with my collegiate Irish Catholic coach, Johnny Jordan. So maybe my die was cast. I grew up in a single-parent, Protestant home, the proud grandson of a Methodist minister. Both O’Farrell and Jordan were surrogate fathers to me.

My choice of Notre Dame from among all of the scholarships offered did not sit well with many of my family members. My mother, however, was delighted. I was honored. The moment I set foot on the Notre Dame campus, I had a sense of belonging.

There I was, a hopeful young Black teenager beneath the Golden Dome at one of the most prestigious universities in the world, which happened to be led by a steadfast and resilient civil rights– minded president, Father Theodore M. Hesburgh. Father Ted always preached the dignity of man regardless of race, creed, or color. He marched with the champion of human rights, Dr. King. Father Hesburgh was far ahead of society. He made it perfectly clear to the nation that anywhere Notre Dame’s minority students weren’t welcome, neither was Notre Dame.

With that as a foundation and imbued with a pioneering spirit engendered by Major League Baseball’s barrier-breaker Jackie Robinson, I embarked on my mission.

My goals were to get a great education, become a basketball All-American, and prepare myself to become a productive Black man in a man’s world.

The four years were full of challenges and life-shaping experiences. I feared not making the grade and letting a lot of people down. I told my mom that if I flunked out, not to expect me to return to Chicago to face all of those people—it would be the French Foreign Legion for me! She frowned and said to get back to work.

Through it all, I always felt that I was a respected Notre Dame man in the making, getting a sound, personalized education. Of course, I felt the pressure of being the face of my race. I came to realize that the first and only real Black contact that most whites on campus had ever experienced was me.

So integration at Notre Dame was a work in progress and I wore a hard hat. I was the only Black on the basketball team for four years, the team’s first Black captain, and a two-time AllAmerican. In fact, I was the only Black in every class I attended.

Looking back over my bountiful Notre Dame career, my cup runneth over with indelible memories. My dormitory rectors were watchful and caring. I especially recall my freshman rector at Cavanaugh Hall, Father Robert Pelton. He said to me, “Please let me know immediately if you’re having any problems. We’re counting on you to be successful on and off the court.”

My freshman student advisor, Bill Burke, stressed keeping tabs on my academic problems and getting to him early on. Logic professor Henri DuLac invited me to take his class and promised it would help to organize my thinking and my life. English composition professor Joseph X. Brennan insisted that I dig in and develop the raw talent he saw in me.

Father Tom Brennan, the hard-nosed philosophy professor, taught me in the classroom and helped me with my free-throw shooting. English literature professor Chester A. Soleta told us that poetry was his specialty and he would make it live in our souls.

Boy, did he ever.

Social psychology professor Raymond Murray hammered home that as human beings we all have some psychological frailties. “If,” he said, “there is anyone present who insists this doesn’t apply to him, please leave the room; there is nothing I can do to help you.”

A criminology professor I had was a former warden at Indiana State Penitentiary. He pointed out that prejudice and racism are pervasive, from the psychopathic killer on death row to many of us sitting in his classroom.

Kudos to anthropologist and senior thesis advisor Dr. James Crowley, who insisted that I delve into my African heritage and examine the Dahomey and Asante tribes of West Africa. My protector and teammate John Smyth, now Rev. John Smyth and president of Notre Dame College Prep in Niles, Illinois, was a six-foot, five inch enforcer who made it known that if you messed with me, you had to go through him.

I have never had a more meaningful knock on my door than the one delivered by Notre Dame’s All-American football great and Heisman Trophy winner Paul Hornung.

I answered the knock, and there stood “the Golden Boy.” “Hawk,” he said, “because of you I’m missing out on the best pasta and pizza in town.” Father Hesburgh had put a particular restaurant off-limits to Notre Dame students after I was refused service because of my race.

The ban was to be in effect until I got a public apology.

Hornung went and secured that apology and the restaurant’s doors were opened to all. Talk about All-American performances!

Then there was fellow Chicagoan and teammate Ed Gleason, who bristled during a 1958 NCAA “Elite 8” trip to a still heavily segregated Lexington, Kentucky. The team left the hotel together to go to a nearby theater and, when we arrived, the ticket seller told us we were all welcome: whites on the main floor and Blacks in the balcony.

“Bullshit!” shouted Eddy. “Where can we go where we can all enjoy a movie—together?”

“In the Black section of town,” answered the ticket seller.

Eddy hailed two cabs and we were off to share an integrated evening in the segregated mid-South.

I give credit to 1960 Black engineering graduate Ben Finley for starting Notre Dame’s first Black student union, which was first jokingly called the NND—the Negroes of Notre Dame. Ben, a born organizer, insisted that all the men of color meet in my room (309 Badin Hall) one day after dinner.

Those who were interested crammed into my room and the meeting was on. The session, however, was interrupted by a knock on my door.

Enter two Caucasian classmates and close friends of mine: Joe Mulligan, the pride of Cincinnati, Ohio, and longtime Chicago basketball buddy Dick Chrisgalvis. They criticized us for our separatist efforts and refused to be excluded from all proceedings.

So the founding of the NND was an integrated affair. This story always gets a hearty laugh from my audiences. I close by paying tribute to my all-time best friend, basketball teammate, and roommate: Eugene Raymond Patrick Duffy. Duff died of cancer at age thirty-three.

God, I miss him! I have never been more connected with another human being in all of my life. I stand six feet, five-inches and Duff stood five-feet, six-inches. We were compared to the cartoon characters Mutt and Jeff.

We were poster boys for athletic achievement and integrated friendship. Duff was a baseball All-American and co-captain of the basketball team.

We loved being Notre Dame men and prized each other’s friendship.

Duff’s life story puts the movie Rudy to shame.

How do I feel about my Notre Dame experience? The greatest four years of my life! I still get choked up when they play “Notre Dame, Our Mother” and the Notre Dame Fight Song. Black, white, or polka-dot: “WE ARE ND!”