Sept. 14, 2006

By Lou Somogyi

If a Mount Rushmore were to be carved one day for Notre Dame’s football players, debates would rage on who the four engraved faces should be.

However, there would be two absolutes: George Gipp and John Lujack.

Gipp is immortalized in Irish lore as Notre Dame’s first player to capture the nation’s imagination through his life and death, while Lujack forever remains the centerpiece of Notre Dame’s unparalleled era of excellence in the 1940s that included four national titles and two other unbeaten seasons.

“The two greatest winners of the 1940s were FDR and John Lujack,” said The Pope of College Football, ESPN’s Beano Cook. “But even Roosevelt won only two elections in the 1940s while Lujack won three national titles.”

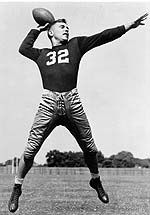

A product of “The Greatest Generation,” Lujack, born Jan. 4, 1925, grew up during the Great Depression, interrupted a prosperous college football career by serving in World War II in 1944-45, and returned to the States to quarterback Notre Dame to national titles in 1946 and 1947, winning the Heisman Trophy in his senior year.

An avid golfer, Lujack’s football skills were analogous to Jack Nicklaus’ career on the links. There were some golfers who drove the ball better than Nicklaus, or putted better, or were more consistent with the mid-range game, chips and short irons…and still others who were more colorful. Yet combine all the elements of the sport, and there was nobody from his era that rivaled Nicklaus.

So it was with Lujack. There were players in his time, including teammates, who ran better, passed with greater efficiency, hit harder, kicked more accurately or appeared more intimidating. But combine every facet of the game – and toss in leadership and charisma for good measure – and no one possessed the complete football package the way Lujack did.

Now 81 years old, the Connellsville, Pa. native looks back in amazement at the path his career took at Notre Dame. In today’s booming world of high school football recruiting ranking services and five-star ratings for the elite athletes, Lujack probably would have been a “two-star” player when he enrolled at Notre Dame in 1942.

“In my senior year of high school (1941), they named four teams all-state in Pennsylvania – and I didn’t make any of the four teams,” Lujack recalled.

“I did make all-county, but then my good friend and teammate Creighton Miller liked to say, `I understand that your high school was the only one in the county.’ That wasn’t true, but it did make people laugh.

“Honestly, I didn’t think I was good enough to get a scholarship to attend Notre Dame. I told people that if I could just make the traveling squad in my junior or senior year, I could probably come back to Connellsville, run for mayor and win it hands down.”

On Lujack’s first day of practice, second-year head coach Frank Leahy asked for a freshmen defensive team to scrimmage against the vaunted varsity. Notre Dame was coming off an 8-0-1 season, but Leahy was installing a new offense, the T-formation, to better utilize the passing skills of junior quarterback Angelo Bertelli, the Heisman Trophy runner-up as a sophomore in 1941. The unit needed all the scrimmage work it could get, even if it meant using the freshmen as cannon fodder.

Lujack just happened to be in the front row of freshman backs when an assistant coach randomly pointed to him and a few others up front and referred to them as “you, you, you and you” to scrimmage with the varsity.

At 165 pounds, Lujack braced himself for the worst. He was lined up at safety and told himself the only way he would survive was to “move forward” and hit with a passion.

“The quick openers with the left halfback and right halfback were coming right at me on just about every play,” Lujack said. “I started making tackles, and Leahy stopped practice three different times to ask who made that tackle. The first time they had to ask my name.

“The next day when we were asked for a defensive team again, they said `Lujack, where are you?’ I raised my hand, and then they said, `You, you and you, go down there on defense with Lujack!’ That’s kind of how it all got started.”

It didn’t take long to recognize Lujack’s skills on offense as well, and Leahy used the 17-year-old freshman in different capacities to prepare the defense. The opener that year was against Wisconsin, led by the legendary Elroy “Crazy Legs” Hirsch.

“If we were going to play a T-formation team, then I was the quarterback that ran the plays against the varsity,” Lujack explained.

“If we were playing a single-wing team, then I would be the single-wing tailback. Sometimes I would run a simple off tackle play and gain seven or eight yards. Leahy would go crazy at the defense and say, `Look at this 17-year-old lad gaining eight yards against you! What do you think Elroy Hirsch is going to do?!? Let’s run that play over again!’

“Well, now everybody knew what play was coming, the defense was steamed, everybody converges on me and I get nailed – but I loved every minute of practice that freshman year. I just thought it was great.”

Eligible for varsity action as a sophomore in 1943, Lujack was actually given the start over the senior Bertelli in the opener because it was at Pittsburgh, near Lujack’s hometown. Bertelli ended up playing most of the game, but Lujack’s start was a gesture of respect from the head coach.

Later that year, after directing a 6-0 start, Bertelli began basic training with the Marines on Nov. 1 in Parris Island, S.C., putting Lujack behind the throttle. His first three starts came against No. 3 Army, No. 8 Northwestern and No. 2 Iowa Pre-Flight, all Irish victories in which Lujack excelled on offense and defense to lead Leahy to his first national title.

Not even a 19-14 loss to semi-pro Great Lakes in the closing seconds of the finale was enough to sway voters to knock Notre Dame from the No. 1 perch. That year, the Irish defeated the teams that finished Nos. 2, 3, 4, 9, 11 and 13 in the Associated Press poll.

After the season, Lujack joined thousands of other college players in World War II duty overseas before returning in 1946 and becoming the first – and still lone – quarterback to direct three major college national titles.

While his career passing statistics .514 completion percentage, 2,080 yards and 19 touchdowns are pedestrian by today’s standards, measuring Lujack by his passing output would be like judging Bill Russell by how many points he scored during the Boston Celtics’ dynasty in the 1960s, or evaluating Derek Jeter by how many home runs he hit when the New York Yankees won four World Series titles in the five years from 1996-2000.

Ironically, Lujack’s signature play was his open-field, touchdown-saving tackle of Army’s Doc Blanchard, the 1945 Heisman winner, in the 0-0 slugfest of 1946 versus the two-time defending national champs. It remains the most famous tackle in school history and helped Notre Dame achieve another national title.

“I’ve been asked many times, `Were you better on defense or offense?’ ” Lujack said. “I didn’t feel I was better in one or another, but I thoroughly enjoyed playing both ways.”

During his abbreviated, four-year career with the Chicago Bears, Lujack intercepted a rookie record eight passes, threw for an NFL single-game record of 468 yards the next season, and made the Pro Bowl in his last two years.

Oh, by the way, because he also was the kicker, he led the Bears in scoring in all four of his years. What else would you expect from the last four-sport monogram winner from Notre Dame? One time in the spring of 1944, the quarterback in football and starting guard in basketball had three hits in a baseball game and, between innings, won the high jump and javelin in a track meet.

No wonder in 1951 Lujack was on the Wheaties cereal box!

Before embarking on his career as a partner in the automobile dealership business, he served as an assistant for Leahy in “The Master’s” last two seasons, when the Irish finished No. 3 (1952) and No. 2 (1953) in the final AP poll. Many years later for Sport magazine, Lujack shared one of his favorite lessons from Leahy,

The Irish head coach was a stickler for perfection and would repeat a play in practice until it met his standards. Consequently, the same running back on a certain call would sometimes absorb a lot of punishment while repeating the play. On one occasion, a back who had a reputation for faking injuries after three or four plays repeated that act. Lujack recalled Leahy going over to this player.

“Lad, I’ve been watching you on every play,” Leahy said, “and I realize that this bodily contact is starting to get a little bit tough, because you keep getting hit. But lad, if I were to let you disassociate yourself with this scrimmage, when you’re not wounded like you say you are, I would be doing you a great injustice.

“If this were to become a habit with you, then later in life when it came time to make an important business or family decision, you might also fake an injury. This we won’t have from a Notre Dame man. So lad, get back in the scrimmage.”

After that, Lujack said, the back had a better appreciation of what was expected of him, and he became a better man for it.

There were minimal expectations for John Lujack when he enrolled at Notre Dame in 1942. He graduated as the ultimate Notre Dame icon, and to this day he remains the model Notre Dame man.

John Lujack By The Numbers

2 Consecutive seasons (1946-47) where Notre Dame teams quarterbacked by Lujack not only won national titles but never trailed in any of the 18 games. The nine other Irish consensus national champs were behind in at least one and as many as five games.

3 National titles won by Notre Dame (1943, 1946 and 1947) with Lujack as the starting quarterback, making him the lone quarterback in college football history to achieve that feat. USC’s Matt Leinart almost duplicated it in 2005 but was one victory short.

4 Monograms won by Lujack during the 1943-44 school year, a feat unmatched since then in school annals. The football mainstay also started at guard in basketball, was an outfielder in baseball and high jumped and threw the javelin in track.

5.4 Yards per carry averaged by Lujack on his 81 career carries. Before taking over at quarterback as a sophomore for the 1943 national champs, Lujack also lined up at halfback.

7 Members from Notre Dame’s 1947 national champs enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame. In addition to Lujack, the other six are George Connor, Ziggy Czarobski, Bill Fischer, Leon Hart, Jim Martin and Emil Sitko.

21-1-1 Career record as Notre Dame’s starting quarterback. The .935 winning percentage is the best in school history among Irish signalcallers, with Tony Rice’s 28-3 (.903) ledger from 1987-89 coming in as second best.

35 Age of Lujack when he was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1960. It made him one of the youngest player ever enshrined. In contrast, 1964 Notre Dame Heisman winner John Huarte was 63 when he made it into the Hall this year.

60 Minutes played by Lujack in the epic 0-0 tie with No. 1 Army in 1946 that later helped Notre Dame claim the national title. Lujack also played all 60 minutes in the 14-13 victory over No. 2 Iowa Pre-Flight in 1943, another national title year.

81 Age of Lujack today, making him the second oldest living Heisman winner, only 24 days behind 1945 recipient Felix “Doc” Blanchard of Army. Ironically, Lujack’s tackle of Blanchard in the open field during the 0-0 tie in 1946 is his most remembered play.

468 Passing yards accumulated by Chicago Bears quarterback Lujack during a 1949 victory over the Chicago Cardinals. The output was an NFL record at the time and is still the most in Bears history.

10 Questions With John Lujack

By Lou Somogyi, Blue & Gold Illustrated

Growing up in the 1930s in Connellsville, Pa., one of John Lujack’s favorite childhood memories was listening to Notre Dame football games on the radio. On a piece of paper, he would draw the lines of a football field and chart the progress of the game.

By 1942, Lujack was suiting up for Frank Leahy’s Fighting Irish en route to one of the most glamorous football careers ever. After helping lead a national title drive in 1943, he served a two-year World War II naval stint aboard a sub-chaser off the coast of England in 1944 and 1945 before returning to Notre Dame to help engineer two more national titles.

With his All-Pro career on both sides of the ball cut short by an injuries, Lujack coached with Leahy for two years before going into the automobile partnership business with his father-in-law in Davenport, Iowa. Retired since 1988, Lujack has established a generous academic scholarship endowment at Notre Dame.

These days, the 81-year-old grandfather Lujack splits his time residing in Bettendorf, Iowa and Indian Wells, Calif. with his wife of 58 years, Pat.

Question: What was your introduction to Notre Dame football?

John Lujack: I think the first game that I can remember listening to was the Ohio State-Notre Dame game in 1935 when I was 10 years old. We had a Philco radio which stood very high on some stilts. My head was under that radio, and when (Bill) Shakespeare threw that winning pass to Wayne Millner in the closing seconds for the 18-13 win, I was a Notre Dame fan for the rest of my life. In my senior year of high school, I remembered listening to Notre Dame-Arizona when it was Leahy’s first game in his first year, and a guy by the name of Angelo Bertelli was the single-wing tailback. It seemed to me like he completed every pass that he threw (Bertelli completed six of seven passes in the first quarter) and Bob Dove, who was an All-American end, was on the receiving end of most of them. And I said, “Boy, oh boy, that Bertelli is some kind of a player!” To be on the same team the following year in 1942 as a freshman – and to scrimmage against Bertelli and the rest of that team – it was like dreams coming true for a young kid.

Q: When Bertelli had to leave Notre Dame halfway through 1943 to join the Marines, you had to step in as a sophomore – yet still won the national title against the country’s toughest schedule. Were there any nerves on your part?

JL: I had played an awful lot in my sophomore year even before Bertelli left. Somebody had written it up that I averaged 43-and-a-half minutes per game as an 18-year-old sophomore while playing both offense and defense. I didn’t come close to those kind of minutes in my junior and senior years because we were winning so decisively that other players were able to see more action. As a sophomore, I was playing both ways, I was scrimmaging against the varsity in practices…so you had enough confidence in your ability that when Bertelli – who was the best pure passer I had ever seen – left in mid-season, it didn’t feel like there was any added pressure. You just kind of figured, `Let’s go! Let’s do the things the coach would say and let your ability take over.’ Maybe I had pressure, but I was dumb enough not to recognize it. I didn’t feel it at the time.

Q: What did you appreciate the most playing for Coach Frank Leahy?

JL: Frank Leahy was as good a fundamentalist as any coach I’ve run into – and I played in Pro Bowl games, college all-star games…I’ve been around a lot of the great ones but he was the best. Leahy covered all the intricacies of football, from the weakest thing to the strongest. We had a meeting one time with the quarterbacks and his question was, “In the event that you were going to take an intentional safety in the end zone, how would you go about doing it?” We said we’d take one knee when we’re just about to be hit. His answer was, “No, no, you run out of the end zone! That way no one could touch you and there would be no chance of a fumble.” That’s just one example of the little things that he covered daily. Any situation in a game you were involved in, he had already covered, so you never felt unsure once it was time for the game. He did the same for your business life, personal life and spiritual life. In 1952 and 1953, after I had retired from pro football, I was the quarterbacks coach at Notre Dame, and Ralph Guglielmi and Tom Carey were the quarterbacks then. I never enjoyed two years as much as I enjoyed working with Leahy and coaching the kids at Notre Dame.

Q: Do you think Coach Leahy’s methods as a martinet would work today?

JL: I think he would be every bit as good today as he was back then. If you’re going to be a great coach, you have to have discipline, you have to have fundamentals, you have to have the players’ respect, and you have to be able to teach and adjust to different things in the game. None of that changes in coaching. In Leahy’s first year at Notre Dame (1941), he was undefeated. But then the next year he changed to the T-formation, a complete change in Notre Dame’s past philosophy. Now, when you’re undefeated in your first try, how many people do you think would change things? That just shows you how he was. He recognized that the T-formation was going to be the formation of the future and what happened in the past didn’t matter.

Q: Although you are recognized mainly as a quarterback, your defining play was the open-field tackle of Army’s Doc Blanchard in 1946 to preserve the 0-0 tie. That eventually helped win the national title. Have you have ever met Blanchard since then?

JL: I met Doc Blanchard about 25 years ago and he said to me, “Do you remember that tackle you made on me in the 1946 game?” I said, “I sure do!” And he says, “Boy, you scared the hell out of me!” So I puffed out my chest and I said, `Really, how?’ He said, “I thought I had killed you.” That’s a made-up story, but it’s a good banquet story.

Q: So you’ve never met Blanchard?

JL: No I haven’t, but I spend a lot of time in California where Blanchard’s old running mate, Glenn Davis, lived. Over the course of his lifetime we played many rounds of golf together and we recalled that Army game where both offenses weren’t good that day and maybe the coaches were too conservative. I think that was one of the poorest games I played. One time we were kidding over a couple of beers and Glenn said, `That was a very lucky tackle because you caught Doc by the last shoestring.’ He said it was the worst tackle he had ever seen.

Q: Were any other defining games in your career that you remember more fondly than that Army game?

JL: As an 18-year old I played all 60 minutes against the Iowa Pre-Flight, a semi-pro team that was assembled during the war. We were ranked No. 1 and they were No. 2, and we won 14-13. Perry Schwartz was an all-league end in the NFL and I was guarding him on defense. He comes down about 12 to 14 yards and breaks out to the sideline toward the Notre Dame bench. I’m on him pretty good but the pass is out in front of me, so I try to knock it down with one hand. Well, for some strange reason, the point of that ball stuck in the middle of my hand and resulted in a one-handed interception. Jim Costin, the sports editor at the South Bend Tribune, wrote that up as one of the greatest plays he’s ever seen, but I think it was lucky that the ball kind of stuck in there. In pro ball, the last game of the season in 1949, my team, the Bears, are playing the Chicago Cardinals, who had the `Dream Backfield” with Elmer Angsman (also from Notre Dame), Paul Christman, Charley Trippi and Pat Harder in the backfield. I threw six touchdown passes that day in a win and two more were downed on the one-yard line. I had 468 yards passing – and that is still a Bears record.

Q: Who’s the greatest Notre Dame player you’ve ever seen?

JL: There were so many good linemen. George Connor, Bill Fischer, Leon Hart, Jim Martin…but the one player who always stood out in my mind was Creighton Miller. In 1943 against Michigan in a toss-up game up there, he made two 75-yard runs and we beat them 35-12. He led the nation in rushing that year and no other Notre Dame back has done that. He was very fast, very tricky and he weighed 195 pounds, which back then was quite significant.

Q: What do you think of the Heisman hype today?

JL: It’s something I certainly wasn’t familiar with in our day. When I was notified I won the Heisman in a telegram after the 1947 win at USC to end the season, I was the most surprised guy in the world. Winning games for Notre Dame was all that mattered to me. You can’t be out for yourself. You’re out for the team. If you check my records, I threw about 10 passes per game – and people do that in one quarter these days. Today a freshman or sophomore can be coming in and a newspaperman says, `Boy, he has Heisman potential!’ I think that puts a lot of pressure on a kid to perform maybe differently than he would naturally perform. If I were in the media, I would maybe write the same stuff, but it does add a lot of pressure. I remember Brady Quinn as a freshman and sophomore quarterback, he was getting killed back there because the blocking for him wasn’t as good as last year. No one was talking about him as a Heisman candidate then. But here’s a guy now with passing records that I don’t think will be exceeded. I mean he had 32 touchdown passes and just seven interceptions – that’s just absolutely amazing. If he has that kind of year again this year, he’ll win it hands down and God love him for it.

But again, you’ve got to feel some pressure, you’ve got to feel that you’ve got to win, you’ve got to throw the pass, you’ve got to do this…that can work on you a little bit. But with Charlie Weis in there, he’s going to calm everything down and Brady Quinn will have one of the all-time great seasons.

Q: You were part of the `Golden Age’ in Notre Dame football. In the last decade, there have been a lot of false alarms about returning to glory. The feeling is now under Charlie Weis the program is about to embark on another era that might not be as prosperous as Leahy’s but something similar to the Ara Parseghian or Lou Holtz years.

JL: And I think Notre Dame needs that. I’ve always felt that the love of Notre Dame is not built necessarily around the academic standards. Now don’t get me wrong, that is extremely important and I know that. But when you’re talking about alumni who are 50, 60 years old, the mystique of Notre Dame is built around winning football, and that started all the way back with Rockne. You’ve got to win football games. If Notre Dame was to go 6-6 for the rest of our lives, don’t you think that the people that grew up following and loving Notre Dame would be very disappointed, downhearted and distressed about what has happened? Nobody wants to see a proud tradition just fade away when you grow up with that mystique and pass it on from generation to generation. I think winning football helps Notre Dame in all aspects. Under Charlie Weis, I think you will see a return to the Leahy, Parseghian, Holtz years. I think Notre Dame has made the greatest pick of anybody to coach this program.

Notre Dame’s seven Heisman Trophy winners get together in December of 1987, the night before Tim Brown was presented the award. The Irish honorees are (from left): John Lujack, 1947, Angelo Bertelli, 1943; Leon Hart, 1949; Tim Brown, 1987; Paul Hornung, 1956; John Huarte, 1964 and John Lattner, 1953.

|

A Player For All Time How revered is John Lujack’s college career?

In collegefootballnews.com’s list of Top 100 greatest players, Lujack ranks third among Notre Dame alumni. George Gipp came in at No. 4, George Connor (who played at Holy Cross in 1943) at 49 and Lujack was 61. Other Irish players included Tim Brown (64), Leon Hart (66), John Lattner (73), Raghib “Rocket” Ismail (75) and Ross Browner (84).

When Sports Illustrated assembled its College Football All-Century team in 1999, Lujack was one of only five quarterbacks named, joining TCU’s Sammy Baugh, Navy’s Roger Staubach, Boston College’s Doug Flutie and Nebraska’s Tommie Frazier.

In 2005, CBS Sports ran a special on the 10 greatest quarterbacks in college football history. Joining Lujack, Baugh, Staubach, Flutie and Frazier on that list were Alabama’s Joe Namath, Brigham Young’s Steve Young, Florida State’s Charlie Ward, Tennessee’s Peyton Manning and USC’s Matt Leinart.