April 29, 2011

April 27, 2011

By Mark LaFrance

For the past 19 years – through times of trial, tragedy, and triumph – Haley Scott DeMaria has never lost sight of the promise she made while occupying a South Bend hospital bed in the winter of 1992.

It was only a few days after the bus carrying the Notre Dame swimming & diving team back from a meet at Northwestern University crashed violently on the Indiana Toll Road in a heavy snowstorm. The accident left Scott DeMaria paralyzed from the waist down and took the lives of two of her close friends and teammates – Meghan Beeler and Colleen Hipp.

While a host of doctors and nurses were preparing her for a life without the use of her legs, Scott DeMaria – still in shock from the news of her teammates’ deaths – tearfully announced a bold plan to her mother and anyone else who would listen.

“I will walk again,” Haley said. “I will do it for Meghan and Colleen. And when I can swim, I will swim for them too.”

Hours later – almost miraculously – Haley’s toes began to wiggle.

The first tiny step toward her goal was complete.

But there were longer and much more painful steps to follow, and the next year would prove to be the hardest of Scott DeMaria’s life.

She struggled through months of physical therapy, willing herself to walk again by keeping her promise close to her heart.

Just as things were starting to look up, doctors informed her that complications from her emergency surgery the night of the accident had caused her spine to collapse for the second time.

So Scott DeMaria was rushed to San Diego that summer for the first of three major surgeries, the last of which almost claimed her life.

Despite the near fatal results, the final operation was a successful one.

The following weeks of recovery and rehabilitation were some of Haley’s darkest, but the memory of her fallen teammates drove her to keep pushing towards the ultimate goal of getting back into the pool.

That fall she returned to campus, and after another year of difficult practices and training, Scott DeMaria would swim again for Meghan and Colleen on Oct. 29, 1993.

In front of a packed house at the Rolfs’ Aquatic Center, Haley took to the starting block for the 50-yard freestyle. She dove into the pool, powered through stroke after stroke, and completed her improbable and emotional comeback by racing to a first place finish.

The crowd erupted as the results were announced and Haley couldn’t help but smile.

After 22 incredibly difficult months, she had done what seemed impossible only months earlier.

Haley Scott DeMaria had made good on her promise.

Writing A New Chapter

The ending was something out of a Hollywood movie, and for months after the race, major film studios contacted Scott DeMaria and her family to purchase the rights to her story.

But none of the executives would guarantee that Haley would have content control, meaning that the screenwriter and director assigned to the film could alter the plot and change the nature of the characters to fit their vision for the movie.

Scott DeMaria had attained her goal of swimming for Meghan and Colleen, but now that the race had ended, it was becoming evident that protecting the memory of her fallen teammates and staying true to her story would become a lifelong mission.

So Haley declined the offers and put the movie idea to rest.

She finished her swimming career at Notre Dame, moved on to a professional career in teaching and started a family with her husband, Jamie, in 2000.

The movie idea resurfaced in 2003, however, when USA Swimming approached her about working with a studio and developing the film as a way to promote the sport with the general public. Again, Haley voiced her content concerns, but agreed to take a look at some scripts.

It didn’t take long for her to realize that a common problem was a developing.

“After several scripts, they just got worse and worse and there were too many creative liberties taken,” Scott DeMaria said. “The story was too personal for me; I realized that if I wanted the story told the way I felt it should be told, I needed to do it myself.”

Lacking the resources needed to create a major motion picture on her own, Scott DeMaria instead turned to the option of writing a book to chronicle the accident, her recovery and ultimate return to Notre Dame to swim the race for her teammates.

Haley kept a journal throughout the rehabilitation process and combined those notes with her memories and experiences to begin the long and difficult process of writing a first-hand account of her journey.

With the help of co-author Bob Schaller and a foreword by Lou Holtz, Scott DeMaria released “What Though The Odds: Haley Scott’s Journey of Faith and Triumph” in 2008.

While it didn’t hit the New York Times bestseller list, the book sold well and ventured from coffee table to coffee table within the Notre Dame community, as more Golden Domers shared the inspiration with friends and family.

The book also made its way to newspaper critics and journalists throughout the United States, and on May 20, 2008, Los Angeles Times columnist Bill Dwyre wrote a lengthy feature about Haley’s road to recovery and the release of her book.

The article caught the attention of UCLA film professor Bob Thompson, who was quite moved by what he had read. Within a few days, he contacted Haley about adapting the book into a full-length feature film.

As a long-time director and Academy Award nominee for 1973’s “The Paper Chase,” Thompson had a wealth of experience in the film industry and understood Scott DeMaria’s frustration with the Hollywood system.

By releasing the movie without a studio and securing an independent distribution contract, Thompson argued, the movie could stay true to its characters and tell the story in the way the events actually played out. With his filmmaking team, Haley would have final approval on the script and she would act as consultant on aspects of production during the shoot.

For Scott DeMaria, this seemed like an ideal way to stay actively involved in the process while continuing to ensure that the film would serve as a fitting tribute to Meghan, Colleen, and the rest of her teammates and supporters at Notre Dame.

She said yes, and Thompson set off to find his screenwriter.

Reliving The Journey

A heavy rain was falling over the city as Dan Waterhouse made the short drive from his home in South Bend to the University Park Mall in nearby Mishawaka.

Ditching his raincoat at the door, Waterhouse entered the local Barnes & Noble and looked from shelf to shelf in search of the reason for his visit.

After a few moments, he spotted a smattering of people in the corner, gathered around an author finishing up a book signing.

He assumed this must be her, and approached the table. He waited as Haley Scott DeMaria finished speaking with a couple of the visitors, and then took the opportunity to introduce himself.

Waterhouse explained that Bob Thompson had hired him to serve as the screenwriter who would adapt her book into a working script for the film. He would also direct the movie and supply much of its artistic vision.

He had been a student of Thompson’s at UCLA and had worked with him on a couple projects since his days as a student. Thompson had read Waterhouse’s latest script, and identified the South Bend native as the perfect writer to develop a screenplay that centered on a strong female lead character.

The two chatted for a while and by meeting’s end, they had hashed out a plan for the difficult writing process that lay ahead.

Rather than write a complete draft and send the final product to Haley, they decided that Waterhouse would compose around 8-12 pages of work at a time and forward them to her for review.

“By doing a little bit at a time, Haley and I stayed on the same page, remained true to the story and knew we were going in the right direction,” Waterhouse said. “Instead of writing 100 pages and having her say, `Oh no, that’s not going to work,’ we remained in close communication throughout the process.”

In addition to strategizing with Scott DeMaria around 8-10 times per week through phone calls and email, Waterhouse developed a realistic portrayal of the plot and the characters by conducting in-depth interviews with University officials and South Bend figures that played prominent roles in Haley’s recovery process.

He spent afternoons with former University president Fr. Edward Malloy and Notre Dame swimming coach, Tim Welsh. Waterhouse also conducted phone interviews with former athletics director Dick Rosenthal and met with Indiana State Trooper Kevin Kubsch, who was first on the scene when the accident occurred.

During the meeting with Kubsch – who visited with Scott DeMaria throughout her hospital stay in South Bend – the officer shared around 200 pictures with him from the night of the crash. After spending weeks learning about the lives of Meghan and Colleen and developing their characters in his writing, Waterhouse was deeply affected by the photographs.

As Kubsch spoke emotionally about that night, Waterhouse thought deeply about the similarities between this interview and the others he did while on campus.

There was a clear theme of pride and optimism present throughout each session, and in his head, Waterhouse was beginning to develop the static characters of his screenplay into more dynamic individuals with personalities, motives and ideals. In other words, Waterhouse was reliving parts of Haley’s life at Notre Dame to understand the complex relationships that shaped her college experience.

“By the time I finished the interviews, I was starting to get a clear picture of what people mean about Notre Dame being a big family,” Waterhouse said. “That understanding gave this screenplay a whole new dimension because we can not only see the faith in action, but we can also see the responsibilities and the caring of the University itself and the citizens of South Bend that played a role in Haley’s story.”

The supporting characters in the script were starting to come together, but Waterhouse needed more than just interviews to grasp the persona of Haley’s character and how she fought through almost two years of coping with grief and the arduous rehabilitation process.

So he began spending more time on campus and around town, walking in the footsteps that Haley took in the aftermath of the accident. He visited Memorial Hospital where she spent so many months of 1992.

And to develop a particularly poignant scene in his screenplay, Waterhouse recreated one of the most difficult experiences of Scott DeMaria’s time in South Bend.

When she was first released from the hospital in the spring of 1992, Haley paid her first visit to Meghan Beeler’s grave on campus.

Waterhouse wanted to know exactly what Haley would have thought and said during that emotionally draining moment, so he made his way to the gravesite and parked exactly where her mother had stopped the car.

“I knew from her journal that Haley believed Meghan and Colleen were with her all the time, but what would she have really said and felt when she got out of the car with her cane and went through the snow to Megan’s grave?” Waterhouse wondered. “The only way I could know that was to physical realize where that car parked and how many steps it was to that grave site – to stand there and feel it.”

It was insightful research and personal visits like this one that transformed Waterhouse’s screenplay from a two-dimensional book of lines and cues into a vivid, almost first-hand account of Scott DeMaria’s story.

“The visits and interviews really paid off because Haley was kind of awestruck by the detail,” Waterhouse said.” She would ask, `It’s not written, so how did you know?’ Bearing in mind that she was always talking to Meghan and Colleen, I had a pretty good idea of what might have been said. But if I hadn’t talked to Kevin and other people that were involved, I never would’ve been able to lay it out in the way that I did.”

Needless to say, Haley was thrilled with the way the script was turning out, and felt confident that the final product would be a fitting tribute to Meghan and Colleen.

After 16 months of consultations, drafts and revisions, Waterhouse and Scott DeMaria finalized and approved a completed screenplay in October of 2010.

It was time to move on to phase two of the project.

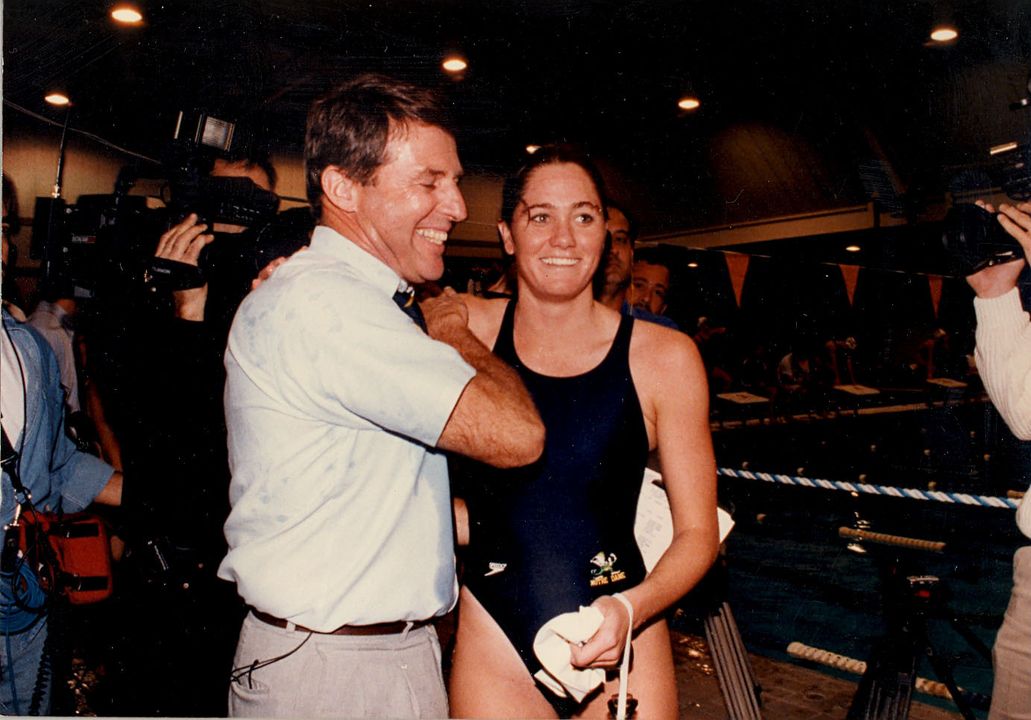

Waterhouse (left) and Scott DeMaria (right) during a television interview

|

A Local Flavor

When most people think of Notre Dame on the silver screen, it’s “Rudy” that comes to mind.

The film perfectly captures the legacy of the Notre Dame football program and the mystique of the University, and viewers often feel like they’re right alongside Rudy as he fights for his dream to play for the Fighting Irish.

While much of the movie was shot on campus, a number of the scenes that take place in South Bend were actually filmed in Chicago and Los Angeles.

This didn’t sit well with Waterhouse at the time, who as a South Bend native, felt the city deserved more of a showcase for its role in supporting Notre Dame and the athletes who walk through its hallowed halls.

The support of the city played an important role in Haley’s life after the accident and throughout her recovery. She was flooded with words of encouragement from passersby on her trips to and from Memorial Hospital that winter, and updates on Haley’s condition were given regularly through local print and broadcast media.

“As the story unfolded during my research, I discovered how much interaction there was between Haley’s family and the South Bend community,” Waterhouse said. “We feel like we have a responsibility to give back to the city with this film.”

Scott DeMaria couldn’t have been happier when she heard of Waterhouse’s plan.

“One of the things that I love about the project is that Dan and his team are very committed to doing as much shooting as they can in South Bend,” Scott DeMaria said. “They’ve done a lot of legwork. They’ve contacted and been in touch with Memorial Hospital, they’ve had conversations with the Indiana State Police and we’ve gotten a lot of local businesses on board who are willing to help with the project.”

Keeping it local has become somewhat of a theme with Waterhouse’s production team, which will be composed of key industry professionals, but also employ a working crew of freelancers that call the Michiana area home.

Waterhouse and Scott DeMaria always intended to shoot the majority of the film in South Bend, but to do so, they needed one critical request to be granted.

They needed permission to film on campus.

In the history of the University, only two movies have ever been shot at Notre Dame – “Knute Rockne All American” (1940) and “Rudy” (1993). Coupled with the fact that University spokesperson Dennis Brown receives at least three or four scripts a year from individuals who hope to gain filming rights on campus, and you can calculate the success rate of such requests.

Haley was humbled by the fact that the University would even consider her film, and awaited the decision of the University.

Sure enough, in February 2011, officials granted Waterhouse’s production team full access to Notre Dame, expressing that the movie was relevant and powerful enough to warrant an on-campus shoot.

Said University president Rev. John I. Jenkins, C.S.C., “The perseverance, courage and faith that Haley demonstrated in overcoming the critical injuries and medical setbacks she suffered can inspire many and so should be told to the widest audience possible.”

Now that all the pieces are in place, Waterhouse and company are starting to analyze possible casting options and are in talks with a number of A-list Hollywood actors and actresses to play some of the film’s most important roles.

While Waterhouse is hesitant to reveal specific names, he has confirmed that the role of Haley will be played by an unknown actress from the South Bend area.

“I decided early on that I didn’t really want a recognizable star to play Haley herself,” Waterhouse said. “I don’t want that celebrity to detract from the realness of the character or the impact of the story.”

A similar casting strategy will be employed when searching for individuals to play Haley’s teammates – including Meghan and Colleen. Keeping their portrayal honest and realistic continues to be the driving force behind Scott DeMaria’s decision to make the film.

It is proof of her continuing mission to live out her 1992 promise, and that desire is an important part of the film’s financing and release logistics.

An Independent Production

The decision to produce the film without a major Hollywood studio was made from the beginning, primarily due to Haley’s concerns regarding content control and her desire to give the movie a grassroots, word-of-mouth feel that has defined the distribution of her book.

As such, Haley and her team are solely responsible for funding the film, and they’re currently working to raise enough money to get production started.

Waterhouse has set the film’s budget at $16 million dollars (Rudy was made for around $12 million in 1993), with a financing structure of 25 shares that will be split between private investors, companies, and businesses. Of the $16 million, $9 million will cover production costs, while the remaining $7 million will be allocated for advertising and distribution efforts.

With key advancements in industry technology, Waterhouse and his crew have found invaluable ways to cut costs in the shooting and editing process, while keeping production value at or above the typical Hollywood standard.

The group has also secured a distribution contract with a releasing company, so when Haley’s film is ready for the theaters, they are guaranteed spots in 1,200 carefully targeted cinemas across the country.

“One of the things that I think is unique about the way Dan and his team are working is they’ve completely factored in production costs and distribution costs,” Scott DeMaria said. “So this won’t be one of the hundreds of movies that gets made and is never seen. We won’t have to take it to a film festival in hopes of it being picked up – once it’s financed, it’s guaranteed to be shown.”

Waterhouse was careful not to travel down the same road as the executives of similar inspirational sports films that have struggled at the box office. The 2009 film, “The Express,” which chronicled the career of Syracuse University running back Ernie Davis, is a prime example.

The film had a production budget of $40 million and was released in close to 4,000 theaters. When the over-distributed film only grossed $9 million, the film’s producers were left wondering how to pay back massive amounts of debt to investors.

By carefully estimating revenue from Haley’s film based on a four-week run in a limited theatrical release, Waterhouse has projected that the film will make back it’s budget by the time the film leaves cinemas. That will allow the executive team to repay investors right away and fund the rest of the film through DVD sales and On Demand programming.

It’s a strategy that will likely pay dividends as the filming process moves forward.

“What’s the point of starting something if you can’t finish it?” Waterhouse said. “We want to make sure we guarantee ourselves and the University and everybody else that’s waiting for this film that it’s not going to end up as some incomplete thing. It’s all or nothing, and with our projections, it looks like it’s going to be all.”

Two Miles From Home

The working title of the film will be “Two Miles From Home,” which signifies the distance from Notre Dame at which the swimming bus spiraled off the highway and Haley’s recovery process began.

The production team is aiming for a 2012 release date in order to properly recognize the 20-year anniversary of the accident.

Scott DeMaria hopes that the finished product can impact and motivate all those who decide to share in her story once it hits theaters. While few people have lost two close friends and suffered temporary paralysis, she is quick to point out that almost everyone deals with loss and sacrifice at a given point in their lives.

“There are the themes of believing in yourself and never giving up, but I think most importantly, this story proves that life is tough sometimes,” Scott DeMaria said. “But it does get better and you just have to hold on to that hope.”

It was hope that got Haley out of her hospital bed and back into the pool, and that hope was bolstered by her wish to carry out her promise and properly honor her fallen teammates.

“To me, this is the ultimate tribute to Meghan and Colleen, both the book and the movie,” Scott DeMaria said. “They were such a huge part of my recovery, and I know a huge part still of all of my teammates’ lives and memories. We’re all healthy and happy and successful in what we’re doing, and I think that’s a testament to their memories and how they motivate us on a daily basis.”

Now that the screenwriting process has come to an end, Waterhouse can’t help but find himself reflecting on how lucky he is to be working on such a unique project with an individual like Haley.

From the moment they met on that rainy day to their current relationship as director/consultant, Waterhouse has been awed by Haley’s selflessness and generosity.

“I’m just really humbled that she allowed me to build this screenplay and become her friend,” Waterhouse said. “Every time she comes to Notre Dame, she always gives me a call and wants to know when or where we can meet up. She’s so sensitive and compassionate to other people and if she feels like she can be an inspiration to just one person, she’ll walk up to that person and start a relationship.”

Much like Haley does on an individual basis, Waterhouse is confident that the film will inspire audiences nationwide, and he’s not afraid to make a few comparisons to prove it.

“I told Haley that if this thing can make me feel as good about work ethic as `Hoosiers’ did, if it’s as hard to me to watch `Million Dollar Baby’ was, and if it makes me want to jump out of my seat with excitement like `Rocky’ did, we’re going to be good to go.

This film does all of that and much, much more.”

— ND —