Feb. 22, 2011

EDITOR’S NOTE: The following is one of 20 profiles from the recently-published holiday book entitled “Strong Of Heart: Profiles Of Notre Dame Athletics 2010.” The book was produced by the University of Notre Dame Athletics Department and edited by senior associate athletics director John Heisler, with University photographer Matt Cashore coordinating all art for this publication. It can been viewed in its entirety in a PDF format by CLICKING HERE or it may be purchased either on-line by or through the Hammes Notre Dame Bookstore, with a portion of the proceeds from this project going to the Matt James Scholarship Fund and the Declan Drumm Sullivan Memorial Fund.

By Al Lesar

Sometime soon, Teddy Hodges may have a difficult letter to write.

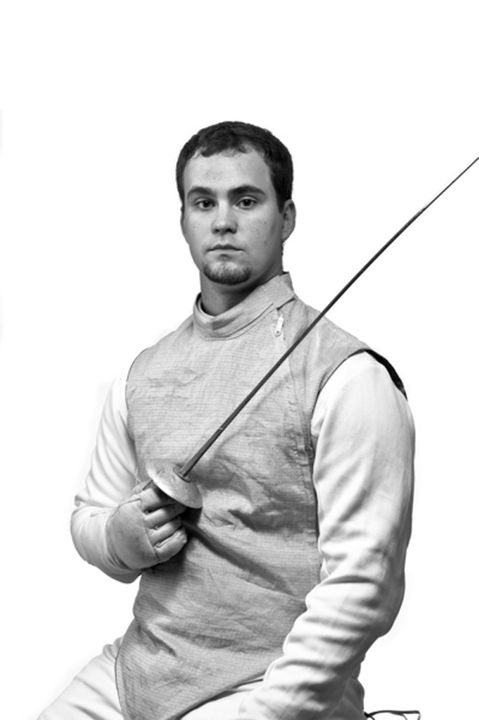

A senior English major at Notre Dame with a talent for debate, the 22-year-old fencer from Salina, Kan., isn’t used to being at a loss for words.

This fall marked the one-year anniversary of Hodges’ heart transplant.

“It’s a happy anniversary,” Hodges said.

He knows that for someone it’s a sad marking of time. Someone lost a loved one to give him a second chance at life. Transplant protocol allows for no direct communication between the recipient and the donor’s family through the first year. If both parties agree, correspondence can then happen.

“I’d want to give [the donor’s family] a great sense of thank you,” Hodges said, struggling for the right words. “God bless. It was a heart-wrenching moment in their lives. I hope they’d be able to look at me and see a little bit of happiness.”

Hodges is happy. The 6-foot-2, 220-pounder walks around campus with a smile on his face. Like he’s seeing it for the first time in his life.

“Every time I walk on campus, it’s even more beautiful than the last time,” Hodges said. “I feel older. Grown up. I enjoy things more. It’s important to enjoy life.”

Ted, the son of a physician, always was an athlete growing up. His parents steered him toward fencing at seven years old, but never pushed. He gravitated toward football and played on a state championship high school team as a senior.

He spent his freshman year as a walk-on defensive back with the University of Kansas football team. When he lost sight of a future in football, Hodges looked up his old fencing coach, Gia Kvaratskhelia, an assistant at Notre Dame.

“Teddy’s certainly a special person,” Kvaratskhelia said.

He transferred for the start of the 2007-08 school year, sat out that fencing season as per NCAA rules, then contributed in the foil competition the next season.

The end of the 2008-09 school year was a blur. Still is. He watched some friends graduate, with President Barack Obama as the commencement speaker. Spent a day in Salina. Flew to Albany, N.Y., to judge a debate competition. Spent another day in Salina. Flew to Texas to hunt with some friends. Returned home to spend some time with his brother Grant, also a Notre Dame fencer.

“I was beat physically,” Hodges said. “So much of that I don’t even remember.”

For good reason. High fever. Nausea. Lethargy.

Fortunately for Hodges, a Salina doctor recognized the symptoms. Viral myocarditis, an infection targeted at the heart. This was serious.

A 45-minute helicopter ride to Kansas City started with Hodges going into cardiac arrest and ended with a second episode. Life left his athletic frame.

“Two big guys pounded on me (CPR) for 39 minutes,” Hodges said. “I’m thankful they refused to quit.”

Hodges spent the next three months hooked up to a heart-lung machine the size of a small refrigerator, with two tubes inserted in him. A stroke during that time was a setback.

“The stroke was one of the worst feelings,” Hodges said, the English major in him coming out. “I couldn’t conjugate nouns or verbs. Mentally, I could visualize what I wanted to say, but I couldn’t make it happen.

“I kept the notes I made. I look at them now, it’s just chicken scratching.”

Therapists–physical and speech–made a difference. He gradually gained strength and regained his speech skills.

He was ready for a transplant. By early September 2009, circumstances made a candidate heart available.

“My attitude was, `Let’s get this thing done,'” Hodges said.

It happened on Sept. 16. The frequent trips to Notre Dame’s Grotto by fencers; the prayers from the entire Notre Dame community; the support of his hometown; the expertise of the hospital staff– it all came together for a positive outcome.

“I’m so fortunate,” Hodges said. “I’ve had a lot of people pulling for me, a lot of different communities. So many people have become new friends through this.”

Occasional visits to campus last year kept his spirit focused.

“This is such a wonderful place,” Hodges said, glancing around at the tree-draped backdrop surrounding the Grotto.

“This is one of the most spiritual places I know,” he said. “I love coming here.”

Hodges has been medically cleared for competition. He still has a regimen of medication. Tests are frequent. Training is a bit different, but conditioning will come. Weight lifting. Sprints. Distance running. No restrictions.

“My warm-up is slower than most people’s,” Hodges said. “Once I get my pulse up there, it’s no different than before. If I feel bad, I slow down.”

The progress Hodges has made through the first couple months of conditioning has been impressive.

The improvement, though, has come with a bit of reprogramming.

An athlete good enough to play any sport at the college level is taught to push himself and test his limits. In Hodges’ case, he’s smarter than that.

“I hold the trump card,” Hodges said. “I’m the one who realizes when it’s time to back off. I’ll push and push, then realize, hey, it’s time to rest a bit. I’ll just go off to the side and stretch.”

Kvaratskhelia points toward the Notre Dame Duals in early February 2011 as Hodges’ likely coming-out party.

“No doubt, Teddy’ll be ready,” Kvaratskhelia said.

He’s already ready to start paying it forward.

During his time in the Kansas City hospital, and in the period since the transplant, Hodges has had mentors.

He’s gotten to be friends with a transplant patient who has resumed his activity as one of the country’s top handball players. He’s developed a relationship with a former banker who retired and has embarked on a second life by moving to an exotic island and opening a business.

Make the most of the second chance.

The tables have turned on Hodges. Just recently, he’s become the mentor.

“I got a message on Facebook from a guy in his mid-30s,” Hodges said. “He’s got long-term heart failure. He’s scared. He’s worried. He’s married and has kids. At least for me, I’ve had this at a decent time in my life.”

In reality, there’s no “decent” time for such a traumatic event. However, if it did have to happen, his obligations are limited.

After a couple correspondences with this new acquaintance, Hodges, by chance, met the man and his wife over fall break when they were both at the hospital for testing.

He had an opportunity to go to the next level–from mentee to mentor.

“I didn’t want to sugarcoat anything,” Hodges said. “This is a dire situation. There’s no way to get around it. As I was talking, the editing was pretty important.”

Words are Hodges’ friends. His mile-a-minute delivery, reflecting the energy he’s come to have, molded and caressed the ideas he was trying to get across.

“I told him that `You’re gonna get your butt kicked,'” Hodges said. “That just happens. `But, in the long run, you’re gonna be all right.’

“`Once you have the transplant, you should be vigilant. You should worry about it. But, you can’t live your life in perpetual fear. You need to learn to trust other people. Rely on your support system.'”

Hodges’ support system: His family, the medical team that saved his life, teammates on the fencing team and fellow students have been there for him. They’ve taught him a new meaning for trust.

“It’s just amazing that you don’t realize how sick you were until you start to feel better,” Hodges said. “You just got the gift of life. It gives you a new energy that was never there.

“There might be a rough year, maybe two, but once things level out and all the variables are taken care of, life can be pretty good.”

Hodges, actually, is living proof.

“I plan to live a long time,” he said. “I want to be an example. Keep battling. Keep a positive outlook. Just don’t live in fear.”

What scares Hodges?

“I don’t want to sound over the top bravado, but I’m not gonna live in fear,” he said. “I have goals in fencing, my degree. I’m not gonna let my health get in the way.”

Graduation should happen in May 2011. After that?

“I want to give something back to the University,” said Hodges, not really sure what that could be.

“It’s like my dad would say about borrowing a car: `Leave it in better shape than when you got it; leave it with a full tank of gas; make sure it’s clean.’ I want to leave this University a little better than when I got here.”

Odds are that might already be the case. Courage. The smile. The attitude. The love for Notre Dame.

Should give him plenty to write about in that letter.

A version of this story originally appeared in the South Bend Tribune. Reprinted with permission.

–ND–