Jan. 9, 2016

By Sonia Gernes

Strong of Heart (2011)

Carol Lally Shields, M.D., may have been the first woman to win the University of Notre Dame’s highest student-athlete award, and she may be one of the world’s leading ocular oncologists, author of over 700 research articles, but she received an F on the first history paper she wrote at Notre Dame as a freshman.

“I walked back from O’Shaughnessy [Hall] in a daze,” she says, but for her the memory doesn’t rankle.

“It charged me up,” Lally Shields says.

“It made me take writing seriously, and now what do I do for a living? I write research papers!”

That spirit of turning any challenge into expertise has characterized Lally Shields’ remarkable career, not only in her freshman year and on the first women’s basketball team at Notre Dame, but also through the establishment of an ophthalmology practice, her career as associate director of oncology at the Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia, the raising of seven children (yes, seven!) and her cutting-edge research in pediatric oncology.

“Never give up,” she tells the young physicians from around the world who are fellows at Wills Eye Hospital, citing a mantra from Winston Churchill: “Never give up. Never give up.”

Lally Shields saw herself as “ordinary” when she came to Notre Dame in 1975, a girl from the steel town of Sharon in western Pennsylvania who worried she was less prepared than many of her classmates, though she was undaunted by the fact that the University had so recently admitted women. After all, she was following two older brothers to Notre Dame, and she hadn’t been raised to let gender make a difference.

“The overwhelming male predominance didn’t bother me at all,” she says. “Actually, I kind of enjoyed it.”

Lally Shields enjoyed basketball also and had been a star back in Sharon, Pa., but she had no plans to find the court at Notre Dame.

“My singular intention was to get the best education I could find,” she says, and she was concerned that athletics would prove a distraction from that goal. Ironically, a piece of paper “literally torn out of a notebook” changed the trajectory of Lally Shields’ Notre Dame career and became, as she puts it, “the subject of my life story.” That scrap of paper, hanging on the bulletin board of her Farley Hall dorm, announced tryouts for a newly conceived women’s basketball team. Lally Shields tried hard to ignore the notice, but that piece of paper kept “torturing” her.

“Why am I not letting myself try out for the team?” she asked herself. She knew that this sport would set a precedent for women’s athletics at Notre Dame, and that she could be part of that history. She also knew that basketball was one area where she really did excel: “My brothers had taught me the ins and outs of street basketball. I knew how to sneak through and drive a ball like a guy.”

Lally Shields showed up for those tryouts, and the rest is history. Not only did she make the team, she became co-captain three times. She led the Irish with an average of 10.7 points per game in her junior year and averaged 12.8 as a senior. She became the first woman to win Notre Dame’s highest student-athlete award, the Byron V. Kanaley Award for academics, athletics and leadership, and in 2011 she was the first Notre Dame woman to be inducted into the Capital One Academic All-American Hall of Fame, an honor held by only 112 individuals nationwide.

More than the honors, however, Lally Shields values the effect basketball had on the rest of her life: “It allowed me to believe in myself. It allowed me a leadership role … and it taught me teamwork. Life is all about teamwork!” Basketball didn’t hurt her grades either; she graduated in 1979 with a 3.91 grade-point average.

True to her belief in teamwork, when Lally Shields is asked about other “defining moments” at Notre Dame, she talks about people rather than events. She cites Sister Jean Lenz, who was assigned to turn Farley Hall into a women’s dorm, as a mother figure and lifelong friend. Sister Jean, in turn, has written in Loyal Sons and Daughters: a Notre Dame Memoir about Shields’ role in transforming the least desirable area of Farley into the most desirable: “What I never counted on was the amazing influence of resident assistant Carol Lally (’79), who was assigned to oversee this basement enclave. Overnight she stirred the population into community. She called each student by name, created clever social events and designed attractive green T-shirts marked with white letters formed out of steam pipes that spelled ‘Cellar Dwellers.’ She turned the space into prime property. While rooms opened up across campus, the cellar dwellers refused to budge.”

Maggie Lally, Carol’s younger sister and also a basketball player, was Lally Shields’ “clone” on campus and shared some of her definitive moments. Particularly, Lally Shields recalls an autumn evening when she and Maggie went to the Grotto after dinner. Conversing quietly in the gathering dark, they noticed someone coming down the steps and realized it was Father (Theodore) Hesburgh. Not expecting any interaction with the President of the University, they continued their conversation, but Hesburgh walked up and greeted the two of them by their first names.

“We were both speechless,” Lally Shields says. “The number one guy on campus knew me! That just made me feel such a part of the University-a player!”

Lally Shields believes events such as this are what sets Notre Dame apart from other universities: “Notre Dame has a very special way of identifying the student as an individual.”

If Father Hesburgh provided Lally Shields with recognition, chemistry professor Emil T. Hofman provided her with trust. Lally Shields describes Hofman as a man who “cut down the bushes and paved the way for women to accomplish with dignity” in those first years of co-education. Still, she was astounded when he approached her and her roommates, Liz Berry and Mary Ellen Burchett, on campus one day and asked them to be his “test testers.”

“Your what?” they responded, and Hofman explained that he wanted them to take his famous Friday quizzes on Thursdays at noon: “I want to run my questions through the three of you to see if you can find any errors,” he said. This process, of course, was a closely held secret, and the three roommates had to fake the fear and trauma of spending Thursday nights studying for the infamous 7-point “Emil” the next day. They kept the secret for years until Hofman himself gave them permission to reveal it.

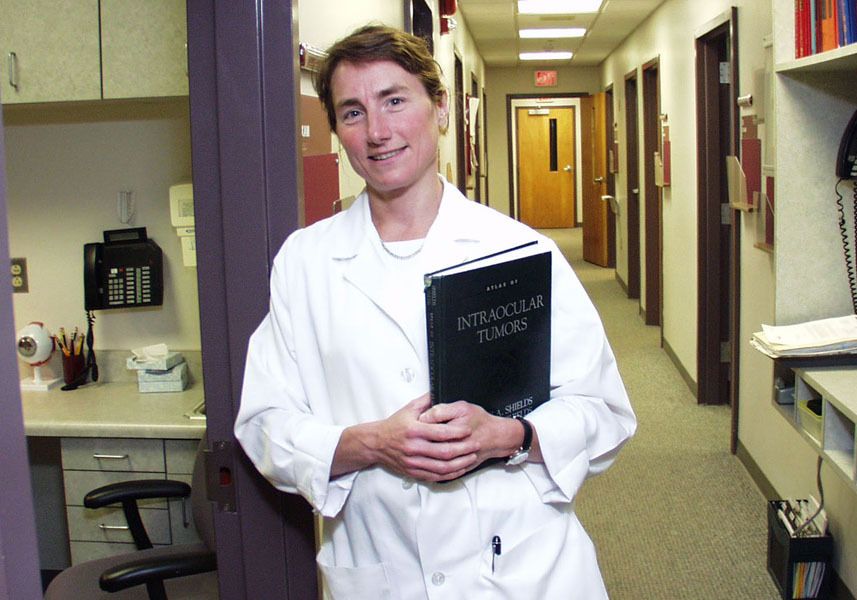

The same grit and determination that overcame a freshman F stood Lally Shields in good stead when she followed her brother Pat into ophthalmology and began to establish her own practice. Ophthalmologists are “precision freaks,” she says, “because every millimeter counts,” but in the early 1980s only about 10 percent of ophthalmologists were women and female retinal specialists were closer to one percent. Lally Shields could see that many of her male colleagues were not comfortable sharing their patients with a woman, and while she might have expected to become established in two or three years, it took her closer to 10. Lally Shields, however, “put [her] head down and plowed through as the Notre Dame offense plows through the defense,” and, in the process, she made it easier for the women who followed her into the field. She also married an ophthalmologist, Dr. Jerry Shields, director of oncology at the Wills Eye Hospital, her partner both at home and on the job. Currently, Lally Shields brings her keenly focused skills to face opponents that are both tiny and capable of taking life: ocular tumors that are sometimes no more than a millimeter in size. She is one of the eight or 10 people in the United States who focus full time on eye cancer, a specialty she calls “the epitome of precision.” Her patients are often tiny, too: newborns whose retinoblastoma may be indicated by a white pupil or a wandering eye. In her work with intraocular melanoma, her microscopic biopsies sometimes contain as few as 10 cells. Lally Shields’ constant concern is determining what is best for each patient, requiring what she calls the “ultimate teamwork” of research, working, for instance, with doctors from the University of California, San Francisco and Washington University in developing chemotherapies to block mutations of ocular melanoma. Her drive to publish and give presentations of this research is fueled by a sense that she “owes” her colleagues for having trusted her with their patients.

Lally Shields’ research in ocular oncology has brought her multiple honors, including an honorary doctorate from the University of Notre Dame and the Donders Medal, given every five years by the Netherlands Ophthalmologic Society for outstanding merit.

She wants it made clear, however, that family is her number-one priority, and that each of us finds our own way to contribute.

For Carol Lally Shields, however, “Every report that I publish is a little baby step for this or that cancer,” and with each discovery, “I feel like Magellan.” –

–ND–