Jan. 12, 2016

As the Monogram Club celebrates its 100th anniversary throughout 2016 we will take a look at some of the remarkable accomplishments of our members. This story, which appeared in the 2012 edition of Strong of Heart, is about Bill Hurd (’69, track & field). Among his many accomplishments and recognitions, Hurd received the Monogram Club’s Moose Krause Distinguished Service Award in 2002.

———-

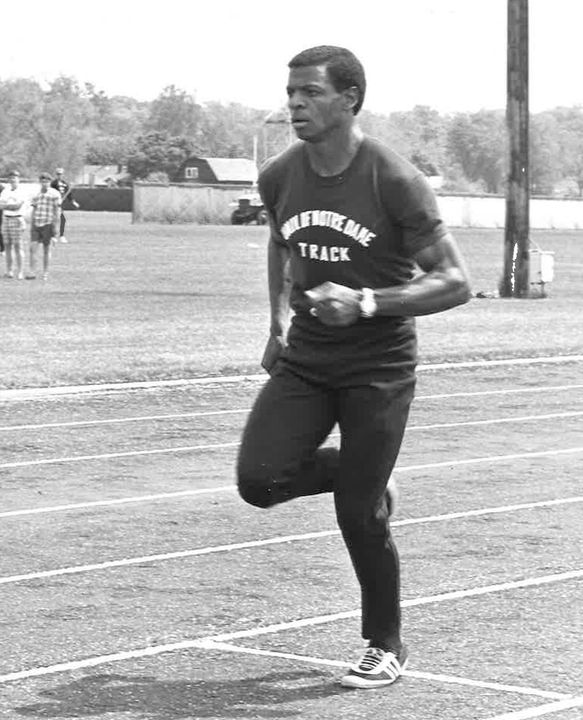

Bill Hurd

A vision for all the world to see.

By Julie Hail Flory

Strong of Heart (2012)

She had heard the coos and cries, felt the touch of the baby’s soft, downy skin, and smelled her sweet newborn scent. But she had never actually seen her grandchild. As the new day dawned on the African island nation of Madagascar, the grandmother’s eyes were wrapped in bandages and the room was brimming with hope. It was time.

Capable hands unwrapped the dressing. First light, then shapes began to emerge. Tearfully, the woman took in the longÂawaited sight of the newest addition to her family. She could see. The grandmother’s tears weren’t the only ones shed that morning. The surgeon who had successfully treated her cataracts also found himself caught up in the moment.

“I almost cried when I saw her crying when she saw her granddaughter,” Bill Hurd says. “She just embraced me. It was very powerful.”

You might think a moment like this would be a once-in-a-lifetime experience. Not so for Hurd, a 1969 University of Notre Dame graduate who has performed countless similar surgeries all around the world during annual service trips that spanned more than two decades from the 1980s to early 2000s. From Senegal to Mexico, Ghana to Trinidad and Tobago, Hurd joined forces with a small team of doctors who dedicated their time, energy and resources to treating those who otherwise would not have received medical care. And it wasn’t as simple as showing up and scrubbing in. “The locations where we did this were places like converted, abandoned schools,” Hurd says. “There were no hospitals. Some of these places were out in the boondocks ââ’¬” no electricity, no running water.”

Constructing operating rooms from scratch and performing delicate surgical procedures in less than ideal conditions, the doctors worked around the clock, not only as healers, but also as administrators, negotiators and project coordinators.

“These mission trips, we didn’t do them with the backing of a church or organization,” he says. “We organized everything ourselves. I’d travel with usually two or three other doctors and we’d do all the groundwork months ahead of time. We sent equipment over to the destination in advance so we wouldn’t have any trouble getting it through customs. These were always very interesting situations.”

Between trip planning, raising his family and managing his own successful ophthalmology practice in Memphis, Tenn. (along with two satellite offices in rural communities), Hurd found himself constantly on the run. But that’s nothing new for him; in fact, it’s right in the heart of his comfort zone.

You see, before anyone realized the surgical talent he would come to possess in his hands, Hurd was already famous for what he could do on his feet. A standout sprinter at Manassas High School in Memphis, he went on to achieve greatness on the track at Notre Dame, where he set no fewer than eight University records and was named Athlete of the Year for 1967-68, beating out some pretty tough competition including football greats Rocky Bleier, Dave Martin and Alan Page, and basketball star Bob Arnzen. He set the American record for the 300-yard dash (29.8 seconds) and had five All-America finishes at the 1968 and 1969 NCAA Championship meets. He barely missed a shot at the United States Olympic team in 1968.

In addition to hitting his stride as an athlete during his Notre Dame years, Hurd also solidified his penchant for service, something he believes had always been within him.

“You either have this or you don’t,” he says. “If you have it, then going to a place like Notre Dame will foster, nurture and develop it, but you have to have something to begin with. For me, I’d attribute a lot of that to my parents, the way I was brought up. Then, when I went to Notre Dame, I saw how service was encouraged. But again, you have to want to help people to begin with.”

Just how he would continue to do that after graduation soon became clear. As an electrical engineering major, he had reveled in the gadgetry and dexterity that was required to solve complex, often delicate problems. After earning a master’s degree in management science at MIT, his thoughts then turned to medical school and he returned to Tennessee to enroll at Meharry Medical School, where he excelled in gynecology and cardiology, but was lured by his love of tinkeringââ’¬”and a good challengeââ’¬”into the field of ophthalmology.

He went on to become the first AfricanÂAmerican ophthalmological resident at the University of Tennessee, which is where it all came together.

“I started doing missionary work during my residency at UT and I kind of liked it,” he says. “There was a doctor there who took me under his wing, and he would take residents to a place every year in Mexico around Thanksgiving. It’s called Ometepec, up in the mountains. There are very poor Mexican people there and we would set up shop and they would always have patients ready for us when we got there.”

After completing several mission trips as a resident, he then started doing them on his own, spanning the globe to offer the gift of sight to those who needed it the most. In one case, however, he might have done the job a little too well.

“There was a guy who was kind of like the Michael Jackson of Madagascar,” he says. “He was a singer and a performer, and his eyes were crossed. So I straightened his eyes, a simple procedure. But after the operation, they were so straight he was worried that his fans wouldn’t recognize him anymore.

“He was very happy they were straight,” he says with a little laugh. “He was just worried about his fans.”

All the surgeries were performed free of charge, but that didn’t stop patients from expressing their appreciation.

“These people were very poor, so we didn’t expect anything from them for our services. But sometimes they knew we were coming and they’d walk many miles to get there,” Hurd says. “Some people would come with something from their farm or something they’d grown in return. We didn’t want to accept anything, but that showed us the level of gratitude.”

With many challenges such as power outages, travel mishaps and even political upheaval in some destinations, was there ever a time he got discouraged and thought about hanging it up?

“Never,” he says in response, without missing a beat.

Now 65 and entering the “twilight of his practice,” he has put the service missions on hold for the past few years, but is getting the gang together again for a trip that’s in the planning stages for 2013. He’s not quite ready for retirement, but has begun to phase out some of his professional activities, cutting back his hours and closing down the two satellite offices.

That doesn’t mean he’s taking it easy. He’s hard at work on an autobiography, tentatively titled Memphis to Madagascar, and his primary practice remains as busy as ever, allowing him to continue to serve patients in his communityââ’¬”and experience those incredible moments when the bandages come offââ’¬”right there at home.

“Almost every day I get that kind of gratification because I do a lot of cataract surgery in my practice,” he says. “Just that procedure alone, you see how you help people.” He plans to keep going until it gets to the point where he can’t do those surgeries anymore. “Then I’m really going to call it quits,” he says.

With a little more time on his hands these days, he’s looking forward to getting back into some of his favorite pastimesââ’¬”golf, tennis and music, which he calls his first love. A talented jazz musician who plays saxophone and flute, he is currently at work on his fourth CD and takes the stage regularly for gigs at local nightclubs.

Still an engineer at heart, he also hopes to pick up where he left off as an inventor. He has held two patents for optical devices, including a slit lamp mountable ocular biometer that was an early model for measuring different parts of the eye in microns.

“That’s another thing I can look forward to,” he says, “developing some of the ideas I have about building medical technology.”

Through it all, Notre Dame has remained a steady presence in the life he shares with his wife Rhynette, a Memphis judge and attorney, and their two sons both of whom studied at Notre Dame, one graduating in 2005 with a double major in computer science and Japanese, and the other transferring to earn his degree from Xavier University and joining his father to help run his practice.

The University has given Hurd numerous honors, including the Moose Krause Award in 2002, and the Alumni Association’s 1992 Harvey Foster Award in recognition of distinguished civic activity. The NCAA also bestowed its prestigious Silver Anniversary Award upon him in 1994 and he remains one of Notre Dame’s most decorated student-athletes, more than three decades since his graduation.

The rest of his story remains to be written, but in his lifetime so far, Hurd has stood as a shining example of the generosity, intellectual curiosity and spirit of service found in so many Domers.

Guess you could say he’s never lost sight of the things that are truly important.

–ND–

Also check out these Strong of Heart stories:

Marty Allen (’58, manager) from 2015

Rev. Edward A. ‘Monk’ Malloy, C.S.C. (’63, ’67, `69, basketball) from 2012

Joe Kernan (’68, baseball) from 2011