Sept. 10, 2010

Oliver’s Story

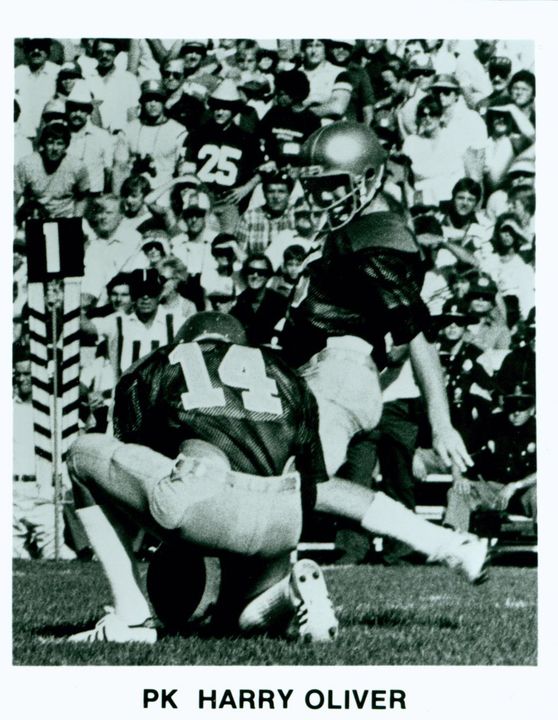

30 years ago, Harry Oliver’s 51-yard field goal against Michigan became one of the most electrifying moments in Notre Dame Stadium history

By Lou Somogyi

Imagine a journeyman baseball player who has hit one home run in three years coming to the plate in the bottom of the ninth with two outs, three on and trailing by three runs.

Add in the fact that he had struck out in his previous at-bat, had a strong wind blowing in — and was told he was allowed only one swing.

A grand slam would seem unlikely.

Yet that was the situation junior place-kicker Harry Oliver faced on Sept. 20, 1980 in Notre Dame Stadium against Michigan. Notre Dame trailed 27-26, and there was time for only one more play — a 51-yard field-goal attempt by Oliver into a breeze.

The Wolverines would win the Big Ten, the Rose Bowl and finish No. 4 nationally that season, but on this day “The Legend of Harry O” would rule the day.

A Kick Start

In 1978, incoming freshman recruit Harry Oliver from powerful Cincinnati Moeller became only the second Notre Dame player to be awarded a football scholarship strictly as a kicker. The first occurred in 1974 with Dave Reeve, a four-year starter who had exhausted his eligibility after Notre Dame’s 1977 campaign.

Prior to Reeve, all the other Irish kickers had been either walk-ons, most notably future NFL star Bob Thomas (1971-73), who hit the game-winning field goal in the 24-23 national title victory against Alabama in the 1973, Sugar Bowl, or they lined up on offense or defense as well.

Listed at 5-11, 165 pounds, Oliver was not going to play another position unless it was going to be on a soccer field. Cut from the team as a freshman cornerback, Oliver did letter two seasons under head coach Gerry Faust, who had discovered him while watching a soccer match.

Benefiting Oliver was his tie to Moeller, which under Faust produced an amazing pipeline of talent to Notre Dame during the 1970s, beginning with offensive tackle Steve Sylvester (1971) and defensive tackle Steve Niehaus (1972), the No. 2 pick in the 1976 NFL Draft.

Also joining Oliver as a 1978 Notre Dame recruit was linebacker Bob Crable, who would earn consensus All-America honors while amassing the most tackles in school history (521). The following year, future first-round tight end pick Tony Hunter signed from Moeller.

Whether Oliver would have been noticed and offered a scholarship had he not attended Moeller is open to conjecture. He converted 37 of his 39 extra point attempts in one of his season, but the National Honor Society’s football résumé hardly seemed sterling.

Unlike Reeve, who in 1974 became the starter from Day 1, Oliver did not make an impact and toiled in the background. Walk-on Joe Unis won the kicking job in 1978, but when Unis struggled early on, Oliver couldn’t beat out another walk-on, Chuck Male, for the top job.

Years ago when he was asked what his defining moment was as a Notre Dame freshman, Oliver responded, “Joe Montana talked to me one time at Goose’s Nest (a bar near campus that long ago was razed).”

Oliver was a freshman when Montana was a fifth-year senior quarterback — and the following year Oliver was issued Montana’s No. 3 jersey.

Notre Dame’s new No. 3 remained the No. 3 kicker as a sophomore in 1979, behind Male and Unis. Unis capped the 1978 season with the game-winning PAT with no time remaining in the dramatic 35-34 Cotton Bowl conquest of Houston, while Male began 1979 by kicking a Notre Dame single-game record four field goals in a 12-10 upset of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Meanwhile, Oliver, the scholarship kicker, was relegated to the junior varsity, where he kicked 27- and 38-yard field goals against Wisconsin.

In the spring of 1980, Oliver hit his nadir. Male and Unis had graduated, but yet another walk-on, Mike Johnston, won the kicking job while starting safety Steve Cichy was assigned to handle the kickoffs and field goals of 45 yards and beyond. Oliver had neither the accuracy and consistency of Johnston, nor the leg strength of Cichy.

“When you come out as the No. 3 kicker … yeah I was down and thought about leaving,” recalled Oliver of a junior year that seemed headed nowhere. “There’s not much hope, but I talked with my parents and decided to stick with it and just keep working hard. Plus, the education was too good to pass up.”

Taking a cue from Faust at Moeller his dedication to continue to try his best was dedicated to Our Lady, in whom he took solace.

In preseason workouts that year, Oliver’s work suddenly began to reap progress. In the pre-game warm-ups for the opener against Purdue, Oliver was approached by his position coach, Gene Smith (now the director of athletics at Ohio State), and was informed that he would be handling PATs and the shorter field goals.

Oliver responded by converting all four PATs and his lone field-goal attempt, from 36 yards, in the 31-10 victory over the No.9-ranked Boilermakers.

Another development also occurred in the kicking game that day: Cichy suffered a season-ending injury seconds after his opening kickoff — meaning that Oliver would now also have to handle the longer field goals. (He had never kicked one longer than 38 yards in a high school or college game.)

Classic Moment

The following week against Michigan, Oliver sensed something in the air — mainly a 20 miles per hour win — during the pregame warm-ups.

“In the warm-ups, I was kicking with the wind,” Oliver recalled. “To give you an idea of how strong it was, I made a field goal from 65 yards out. I felt like I was in a groove.”

After Notre Dame jumped to a 14-0 lead, Michigan rebounded for a 21-14 advantage and had possession of the ball in the third quarter. That’s when the first eerie event of the game took place.

At Notre Dame’s team meeting that morning, backup safety Rod Bone told starting cornerback John Krimm that he had a dream in which Krimm returned an interception for a touchdown against the Wolverines. While Krimm, who had no career interceptions, laughed it off, Bone maintained it was frighteningly real.

With 1:03 left in the third quarter, Krimm stepped in front of a John Wangler pass intended for All-American Anthony Carter and dashed 49 yards for the touchdown.

“I can’t explain it,” Bone said after the game when Krimm directed reporters to ask Bone about the dream.

Alas, Krimm’s score made it only 21-20 because Oliver missed the extra point while kicking with the wind.

“A kicker’s worst nightmare,” Oliver remembered. “You lose by one point because you miss the extra point. I was embarrassed and upset.”

Notre Dame did retake the lead with 3:03 left in the game on a four-yard scoring run by tailback Phil Carter, but when the Irish failed to tally on a two-point attempt, the 26-21 score left the door ajar for Michigan to win on a touchdown with no PAT necessary, thereby heightening Oliver’s anxiety.

Indeed, Michigan scored off a tipped pass with 41 seconds left, but it too missed the two-point attempt to leave their lead at 27-26.

Freshman quarterback Blair Kiel replaced senior Mike Courey as the shotgun quarterback for the final drive, and the Irish caught a break on the first play when Michigan was flagged on a controversial 32-yard pass-interference call that led Wolverine head coach Bo Schembechler into an eruption that would have humbled Mount Vesuvius.

The Wolverines dropped an interception the next play, and forced an incomplete pass on second down. A nine-yard pass to Carter made it fourth and one at the Michigan 39-yard line.

Do the Irish go for it with no timeouts left, or try a 56-yard field goal into the wind with 10 seconds remaining?

Head coach Dan Devine and Co. believed Oliver needed several more yards to have at least a remote chance. A five-yard out from Kiel to Hunter put the ball at the Michigan 34, where Hunter stepped out of bounds with four seconds left.

Oliver, holder Tim Koegel — a quarterback and yet another Moeller alumnus — and long-snapper Bill Siewe trotted onto the field to handle their specialties.

“It crossed my mind that I can’t make this,” Oliver admitted of the 51-yard attempt. “But there really wasn’t time to think. Everything happened so fast.”

That included 1) no timeouts left for Michigan to “freeze” Oliver, 2) no television timeouts because this was the lone Notre Dame-Michigan game since 1978 not broadcasted nationally and 3) the wind supposedly abating to a non-factor when the teams lined up for the kick.

“I’ve heard that from so many of our players or people who were in the stands — that the wind suddenly stopped,” Oliver said. “I didn’t really pay any attention to it because I was just concentrating on the kick. Fortunately, the snap and hold were perfect. I hit the sweet spot and the kick made it through by about three inches.” There was also other good fortune.

“We were allowed to use tees back then and I had a two-inch kicking block,” Oliver said. “I couldn’t see myself making one from that distance with the ball on the ground — and the goal posts now have been narrowed to NFL size.”

Oliver never did witness the kick as it eked past the crossbar.

“I got knocked over during the kick and heard Tim broadcasting it after the hold,” Oliver said. “After it went through, everybody piled on and I was at the bottom. Honestly, it was a little scary with all those big bodies, but it would have been a good way to die, I guess.”

In the mob scene, Oliver nearly incurred a broken leg before fellow Cincinnati native, defensive lineman Joe Gramke, began to help pull bodies off him. “Harry Oliver can have all the ladies he wants tonight,” one Michigan player told reporters after the game.

Oliver, who had to be escorted off the field by security guards, replied, “The only lady I’m interested in is Our Lady.”

The kick sparked a 9-0-1 start and temporary No. 1 ranking for an Irish program that had lost four games a year earlier.

En route to third-team All-America honors by UPI and Football News, Oliver’s left foot never let down after the euphoria versus the Wolverines. In the game after Michigan, Oliver converted a school record-tying four field goals in a hard-fought 26-21 win at Michigan State, and four more a week later to help defeat Howard Schnellenberger’s rising power at Miami.

Later on, his 47-yard field with 4:44 left at Georgia Tech helped No. 1 Notre Dame stay in the national title hunt despite the 3-3 tie against the Yellow Jackets. (Georgia would defeat the Irish, 17-10, in the Sugar Bowl, to clinch the championship.)

Oliver’s 18 field goals (in 23 attempts) easily eclipsed the previous single-season mark of 13 set by Male a year earlier and by Reeve in 1977.

The Last Hurrah

In 1981, Oliver’s senior year, Notre Dame finished 5-6 under first-year head coach Faust, and Oliver converted only six of his 13 field goal attempts.

“There are a lot of undulations in life, and football is a metaphor for it,” Oliver said. “That’s why faith is so important — because it gets you through both the good times and bad.”

Upon receiving his mechanical engineering degree from Notre Dame in the spring of 1982, Oliver’s life was devoted solely to good. For nearly 20 years he served as a senior estimator/project manager at his hometown’s Performance Contracting, and also owned a real estate company. Many of his construction projects were geared towards assisting charitable organizations — Catholic Charities, St. Xavier Project 5000, Feed The Hungry, etc. — and schools in southern Ohio.

On the morning of Aug. 8, 2007, the 47-year-old Oliver’s final hours were spent in a nearly comatose state. Cancer had gradually ravaged his body, but his Notre Dame spirit remained alive. In addition to his brother John and sisters Anne and Mary, by his side was a Dominican friar on the day of the feast of Saint Dominic. One of Oliver’s final requests was hearing Notre Dame music. Unresponsive in his final hours, Oliver began tapping his hand to his thigh when he heard the Victory March.

“If you want a role model for a person, in the way he conducted his life, Harry was the best,” said Faust formerly after his former player’s death. “He was very strong in his faith and went to Mass every day. He had his priorities right and was a great example.

“I never heard Harry say a bad work about anybody, and you never heard anyone say a bad work about Harry Oliver. He loved his life and was great with people. He helped take care of his parents [Harry and Ruth] until they died … I know that Harry is with God and he led a great and giving life.”

Oliver never did marry … but remained true to Our Lady through the end.

Lou Somogyi is senior editor for Blue & Gold Illustrated.

To The End

Excluding overtime games since 1996, there have been only six contests where a Notre Dame kicker booted the game-winning field goal as time expired.

Player (Year) Opponent/Score Yards

1. Joe Perkowski (1961) Syracuse/17-15 41

2. Harry Oliver (1980) Michigan/29-27 51

3. John Carney (1986) at USC/38-37 19

4. Jim Sanson (1996) at Texas/27-24 38

5. Nicholas Setta (2000) Purdue/23-21 38

6. D.J. Fitzpatrick (2003) Navy/27-24 40

Notre Dame has one victory in its history where it scored a touchdown and PAT on the final play — Joe Montana’s 8-yard pass to Kris Haines in the 35-34 Cotton Bowl victory against Houston on Jan. 1, 1979.

-ND-