Oct. 15, 2010

MONOGRAM CLUB CORNER – Kenya Fuemmeler

By Craig Chval

Kenya Fuemmeler always had a plan.

At age seven, touched by the friendship of a Notre Dame student who was her “buddy” at a camp she attended with her cancer-stricken younger sister, she decided to attend Notre Dame.

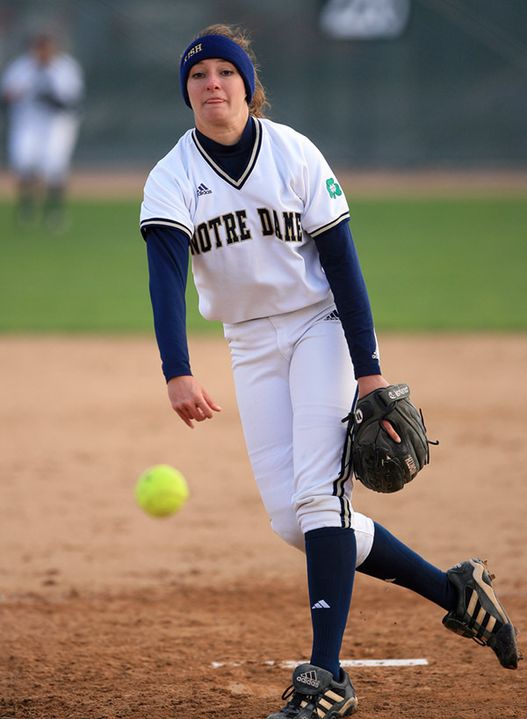

Years later, as a three-sport high school star in Salisbury, MO., (population 1,500), she decided to be a softball player at Notre Dame.

After graduating from Notre Dame, the plan was to attend law school. And now, as the summer before her senior year at Notre Dame approached, the plan called for her to learn more about her future profession and burnish her resume by obtaining summer employment in a law office.

So she leveraged her academic credentials and determined attitude into a non-paying summer position in one of the largest law offices in her home state. By the end of her first week on the job, senior management was so impressed that Fuemmeler found herself transferred into a paid position.

There was just one problem.

“I was miserable in my cubicle because it lacked human interaction,” she admits. “I watched some of the lawyers and what they did, and I could not see myself doing what they did. I saw myself helping more people.”

All of a sudden, there was no plan.

Back at Notre Dame for her senior year, Fuemmeler was persuaded to consider a path she thought she already had ruled out.

“My mom was a teacher and a coach, and I always thought I wanted to do something different,” she says.

But Fuemmeler found herself in the recruiting sights of Teach For America (TFA), a not-for-profit organization striving to eliminate educational inequity by enlisting promising future leaders as teachers in urban and impoverished rural areas of the United States.

As captain of Notre Dame’s softball team and a member of the Notre Dame Student-Athlete Advisory Council, Fuemmeler couldn’t juggle her schedule to attend a TFA informational meeting. But TFA staffer Jack Carey wouldn’t take no for an answer.

“Jack was very persistent and continued to flood my inbox for the next month-and-a-half,” recalls Fuemmeler, who was also battling knee and shoulder injuries attempting to prepare for her final season as a pitcher for the Irish. “Finally, I agreed to squeeze in some time to meet with Jack and hear about TFA.”

At that meeting, Fuemmeler also met with a Notre Dame alumna and TFA member who was teaching in the Bronx, who shared incredible things her students were doing despite “the achievement gap” – the phenomenon that in the aggregate, students from impoverished backgrounds will finish high school performing four to five grade-levels behind their peers from more affluent areas.

Fuemmeler was sold. As fate would have it, she tore the anterior cruciate ligament in her knee the day before she was scheduled to drive from Notre Dame to Chicago for her TFA interview. Chauffeured by a teammate, Fuemmeler made it to Chicago, where she did her entire interview and model teaching lesson on crutches.

Immediately after her graduation from Notre Dame, Fuemmeler had surgery to repair her injured knee. Six weeks later, she was teaching at Locke High School in Watts, Calif. as part of TFA’s institute to teach non-certified teachers the ropes. Her first class had 55 students.

“I was overwhelmed, wondering how I was supposed to teach English to these kids,” she recalls. “It was the hardest six weeks I had ever been through.

“We were working 17, 18, 19 hours a day and trying to be great at what you were doing,” Fuemmeler says.

“But I think my experience as a student-athlete really helped because I had much better time management skills than my peers,” she says. “I learned how to balance time and class and friends and work and that really enabled me to shine at institute because I had gone through that before at Notre Dame.”

After her six-week stint at Locke, Fuemmeler had one week before reporting to Eskridge High School in St. Louis’ Wellston School District. Fuemmeler’s first class at Eskridge met in a boiler room, with 32 students and 15 desks.

“My time at Wellston really highlighted the fact that my kids were so capable of learning, they were simply uneducated, “she explains. “It wasn’t because they lacked the skill to learn, it was because they never had been taught the basics.”

Diagnostic tests revealed that nearly all of Fuemmeler’s 12th grade history students were reading on a fifth-grade level; her 12th grade geometry students were performing at a fourth-grade math level.

“Somebody had passed them through without them having the ability to be proficient at what they were doing.

“Every kid was on a free lunch program – not free and reduced, but free,” she says. “It was poverty driven. My kids’ ability to learn was dictated by the ZIP code that they lived in. Their ability to obtain a quality education was because of where they grew up and that’s unfair.”

Fuemmeler spent two years at Eskridge, teaching as many as five different subjects at a time, coaching track, organizing prom, sponsoring student government, paying for students’ lunches and occasionally providing money so a student could buy a prom dress.

“Anything my kids needed, they got from me,” she says.

As rewarding as those two years were, they were draining as well.

“I was really burned out,” Fuemmeler admits. “And I felt like I just couldn’t do that anymore, because of the time and energy and emotional toll it had taken.”

Having completed her term with Teach For America, Fuemmeler enrolled in graduate school at the University of Oklahoma, where she pursued her master’s in athletic administration while also serving as the academic advisor to the freshman football team.

What Fuemmeler experienced there only deepened her resolve to address systemic educational deficiencies.

“I realized that a lot of these student-athletes didn’t have a fighting chance at college because they were not given an adequate education at the schools that had graduated from,” she says.

So Fuemmeler came up with a plan.

She left Oklahoma and enrolled at the University of Missouri to pursue her master’s degree in education and took a full-time position teaching at Moberly High School, all with an eye toward opening her own charter school in St. Louis.

“My heart lies in urban education,” she explains. “My goal would be that I could train somebody to take my place and leave that school and either open more schools or work in the public policy arena.

“If nobody challenges urban education to get better, then it won’t,” Fuemmeler says. “I’ve seen it and I’ve experienced it, and it’s not fair. Something’s got to change.”

As Fuemmeler reflects on her time at Notre Dame, she can see a common theme that originated with her parents John and Cathy, continued through Notre Dame and TFA and lives on in her passion for improving urban education.

“Looking at my parents, they never restricted what I could or could not do – it was always, `You could do it,'” says Fuemmeler, a four-time monogram winner on teams that won three BIG EAST regular-season championships, one BIG EAST tournament title and made four NCAA appearances. “That’s a big part of the reason I ended up at Notre Dame and a big part of the reason I ended up at Teach For America.

“That’s why I can take on urban education,” she says. “They told me if you dream it, you can be it if you work hard enough at it.”

Hard work and sacrifice were qualities Fuemmeler saw modeled at home every day.

“The sacrifices they made to make my Notre Dame dream happen,” she says, “without them, that would never have become a reality.”

It was that emphasis on family that resonated with seven-year-old Kenya, when Mary Kay (Callahan) Parini befriended her at Camp Quality and then returned for six straight summers to build that relationship.

“She brought me into the Notre Dame family,” Fuemmeler explains.

Years later, Kenya was able to bring her little sister, who recovered from two bouts with cancer to follow in her big sister’s footsteps as a college pitcher, to Notre Dame for a very special family experience. With their parents in attendance, Kenya (Notre Dame) and Chelsea (University of Illinois-Chicago) squared off as opposing pitchers at Notre Dame.

“That, along with putting on my jersey for the first time, was probably my greatest softball experience at Notre Dame,” she says. “It was a pretty special day for the whole family.”

A day that couldn’t have been planned any better.

-ND-