Aug. 7, 2015

While in the Dallas/Fort Worth area Thursday night on business, I flicked on the television to catch the local sports–and there was Tim Brown, front and center.

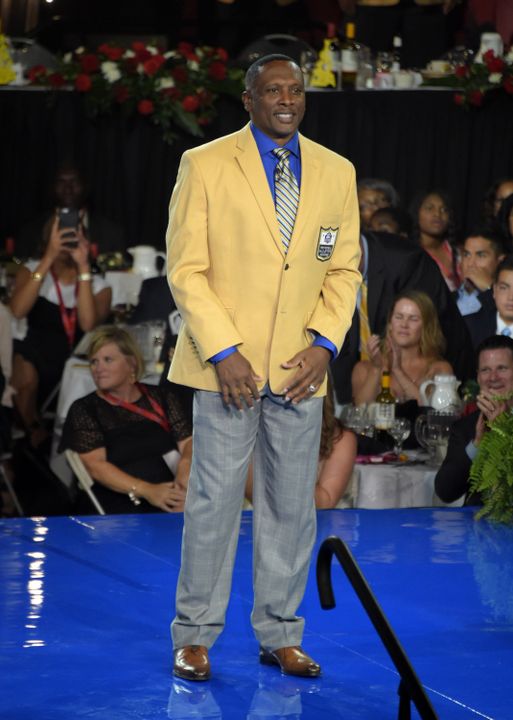

Hometown kid made good in the biggest of ways, Brown had received his hallmark gold jacket at Pro Football Hall of Fame ceremonies in Canton, Ohio. Brown looked as happy as I’ve ever seen him, hands thrown in the air in exultation and triumph.

And why not? For Brown and Jerome Bettis, joining the ranks of the Pro Football Hall of Fame this weekend represents the ultimate endorsements of their careers.

And there are plenty of memories remaining from the days when those two former University of Notre Dame football standouts wore Irish uniforms.

Check out the list of 75 eligible players on the current College Football Hall of Fame ballot and you’ll find only one fullback–Ohio State’s Jim Otis, who played in 1967-69. Fullbacks seemingly have been exiled in favor of slot-backs and extra receivers. Yet former Irish coach Lou Holtz made great and effective use of players like Braxston Banks, Anthony Johnson, Ray Zellars and Marc Edwards–and Bettis was the best of them.

A Detroit product who seemed destined to play for Michigan, Bettis qualified as a great recruiting catch for the Irish. He played on talented rosters that included quarterback Rick Mirer, tailbacks Ricky Watters and Reggie Brooks and underrated receiver Lake Dawson. So Bettis was never destined to be a player to carry the ball 25 times every afternoon (he actually did amass 24 carries twice during his sophomore season in 1991). Yet maybe never have the Irish had a downhill running back with a better combination of power, speed and elusiveness.

Bettis snapshots? There was the Penn State game in the snow in 1992, Bettis’ final year at Notre Dame. With 20 seconds left he caught a three-yard pass that might have provided the tying points–only to see Brooks snare an unlikely two-point conversion throw moments later to win the game. In 1991 he had a career-high 179 rushing yards (plus three touchdown runs) in a 42-26 prime-time road win at Stanford. He also caught a 13-yard TD pass that evening.

USC coach Larry Smith called him the best college football he’d ever seen, and The Sporting News in 1992 rated him the best player in the country regardless of position.

Maybe his most remarkable performance came in the 1992 Sugar Bowl against a once-beaten Florida team. That contest became known as the Cheerios game after Holtz got all sorts of motivational mileage from a joke an Orlando waiter supposedly told him: “What’s the difference between Notre Dame and Cheerios? Cheerios belong in a bowl.” That game also marked a bizarre and yet effective defensive strategy employed by the Irish, who essentially passed on rushing Gator quarterback Shane Matthews and instead dropped almost everybody into coverage.

Only Bettis and the others in the Notre Dame camp will remember what was said in the Irish locker room at halftime of the 16-7 game led by Florida, but it most certainly must have involved a commitment to running the football.

Notre Dame football may never have seen a more dominant half of ground dominance in a postseason environment than what the Irish accomplished in those final 30 minutes against Florida. Bettis scored three fourth-period touchdowns all by himself (runs of 49, 39 and three yards, all within a 4:48 span), and the Irish rolled up 245 running yards just in those final two periods of the 39-28 Notre Dame win. Holtz’s offensive line simply wore down the Gators, and Bettis was absolutely unstoppable.

Bettis’ wide-bodied physical approach on the field belied his polite, soft-spoken nature off the field. Almost always appearing with a smile on his face, Bettis often would come by the Athletic and Convocation Center for Sunday afternoon interviews with national media, generally arriving on his wide-tired bicycle. His late father and other family members were frequent postgame visitors to the Irish locker room in the original version of Notre Dame Stadium.

Brown came to Notre Dame much more intent on earning his degree than achieving football greatness. And it’s probably remarkable that the Dallas product rebounded so impressively from the very first play of his freshman season when he fumbled away the opening kickoff in a game the Irish lost to Purdue to dedicate the Indianapolis Hoosier Dome in 1984.

Later that same season Brown caught three consecutive passes for 59 yards from Steve Beuerlein on the final drive of a game at the Meadowlands in which the Irish had to come from behind with a late field goal to defeat Navy 18-17. Brown most certainly had hopes of being a contributor, yet he readily credits Holtz with recognizing the potential star power in his game and putting him into that hybrid Notre Dame flanker position that gave him a chance to both run and catch the football.

Brown roared into the national consciousness on a 1987 September night in Notre Dame Stadium when he returned two punts back to back for touchdowns against Michigan State. As Brown tells it now, the second return almost did not happen because he was still laboring to catch his breath after the first return (a 66-yarder) and initially indicated to special teams coach George Stewart that someone else should take a turn returning the next Spartan punt. But Brown ended up taking his spot downfield after all, and the result (a 71-yarder for a score) established him as the Heisman Trophy favorite.

Even as Brown appeared to have done enough to remain the favorite to claim the Heisman, East Coast media continued to promote a perceived late push by Syracuse quarterback Don McPherson.

When Tim and I traveled to New York on a Friday for the Heisman announcement, the Downtown Athletic Club staff picked us up at LaGuardia Airport. A visibly nervous Brown could barely bring himself to look at the newspapers in the limo, most of them suggesting McPherson now had a legitimate shot at a come-from-behind win.

The DAC held a dinner that evening for the five invited candidates and their families and institutional staff, and most of the group sat together–most notably Pittsburgh running back Craig Heyward, who wasn’t really expected to be a serious challenger for the prize. Heyward set the tone for the evening–taking every opportunity to enjoy the New York nightlife. Meanwhile, a quiet and reserved Brown sat with his family at a nearby table.

As it turned out, there was no reason to worry. Brown won the award in something of a landslide (he rolled up nearly twice as many points as McPherson and carried the vote in five of six regions). Still, once the official proceedings and interviews were over and the DAC staff and Brown’s group headed off to a nearby restaurant to relax, the mood was as much relief as it was celebratory.

Maybe the most enduring image on Sunday was Brown carrying the Heisman Trophy through the airport (and through security) and watching the reaction of other passengers as they realized what they were seeing. It’s not every day you see a Heisman stowed under the seat of the passenger in seat 12B.