Aug 29, 2013

If there ever were to be an “All-Underrated” Notre Dame football team assembled, dozens of overshadowed or underpublicized names would crop up in the conversation.

At quarterback, there is a Kevin McDougal in 1993, who was sandwiched between No. 2 NFL pick Rick Mirer (1989-92) and National High School Player of the Year Ron Powlus (1994-97) — yet McDougal became Notre Dame’s all-time career pass efficiency leader during the 11-1 1993 season.

Or how about a linebacker such as Wes Pritchett (1984-88). He was the leading tackler for the 1988 national championship team, but received minimal fanfare while fellow linebacker “Amigos” Frank Stams and Michael Stonebreaker received first-team All-America accolades.

If such a team did get put together, its coach would have to be Jesse Clair Harper — maybe the most overshadowed figure in the football program’s illustrious 126 years of history.

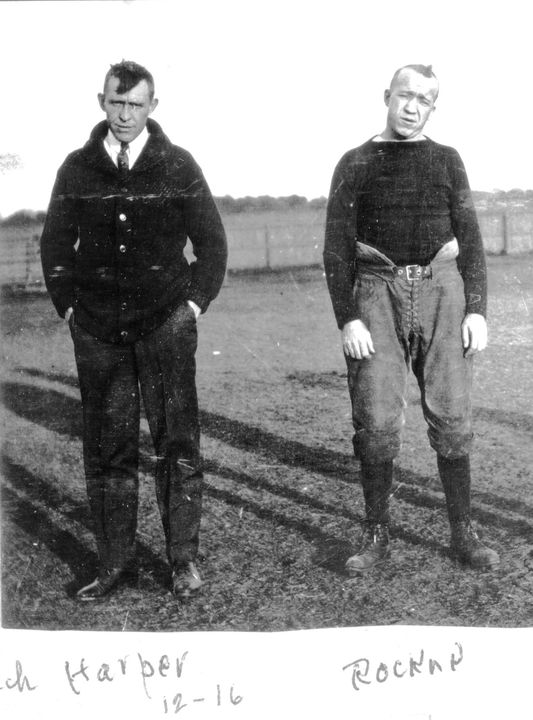

Virtually all stories of Notre Dame’s football usually begin with the Knute Rockne coaching era that started in 1918. He was literally and figuratively “The Rock” upon which one of the United States’ most famous sporting empires was built.

Regretfully, the man who set the table or made a straight path for Rockne, and helped forge the program’s identity for at least the next 100 years, often is in the shadows.

There are six former Notre Dame head coaches in the National Football Foundation Hall of Fame. Five of them are immortalized with sculptures just outside Notre Dame Stadium. Harper is the lone omission. It somewhat defines how he was the man behind the scenes who went relatively unnoticed despite serving the school so well as a coach, administrator, businessman, educator and an example to emulate.

On the 100th anniversary of Harper’s arrival at Notre Dame, the man who mainly stood in the shadows merits more days in the sun.

Man For All Seasons

Born Dec. 10, 1883 in East Pawpaw, Ill., 80 miles west of Chicago, Harper enrolled at Morgan Park Academy in Chicago, even though his cattleman father had migrated to Iowa.

From Morgan Park, where Harper starred in football, it was virtually inevitable that he would matriculate to the University of Chicago, which was coached by the immortal and innovative Amos Alonzo Stagg, whose 314 victories remain tied for seventh most at any level in college football history.

While playing halfback and quarterback for the Maroons, Harper first learned about what it meant to be overshadowed. He played behind Rockne’s idol, and three-time Walter Camp All-American Walter Eckersall (1904-06). During Harper’s senior year in 1905, Chicago was declared the “Western Champion” (the East was more prominent in football) when it snapped the University of Michigan’s 56-game unbeaten streak.

Following Harper’s graduation in 1906, Stagg secured the head coaching position for the 22-year old Harper at Alma College in Michigan. After improving the Scots to a 5-1-1 record in his second season, Harper took a minor step up in 1909 to Wabash College in Indiana, where his first contact with Notre Dame occurred with a 6-3 defeat in 1911 to the football team simply known back then as “Catholics.”

While Harper’s Little Giants of Wabash had made a positive impression on the football field, Notre Dame’s administration was even more taken in by his business acumen, an area where the South Bend school was hemorrhaging in its athletic department. Ostracized by the Western Conference (future Big Ten) because of its small, Catholic identity, the school had 10 different head coaches from 1899-1912. Meanwhile, student managers operated Notre Dame’s athletic department in the ultimate on-the-job training experience outside the classroom.

In its decision to make a greater full-time commitment to its athletic department, which was consistently losing money, the 29-year-old Harper was hired as the school’s first athletics director.

Furthermore, with his approximately $5,000 per year salary (including bonuses), Harper truly was Notre Dame’s “Man For All Seasons” while serving as the school’s head coach in football, basketball and baseball from 1913-17.

Harper’s career record at Notre Dame in football was 34-5-1 (.863), while in basketball it was 44-20 (.686) and baseball 61-28 (.685) for a 139-53-1 mark (.723).

Business Man And Ambassador

Although his official title was athletics director/head coach, Harper developed an even greater legacy with his business savvy and diplomatic skills.

His job description extended into three other crucial areas that would define Notre Dame’s success over the next 100 years:

- National scheduling, or traveling, if not barnstorming, extensively while taking on all comers.

- Generating profit where Harper insisted that “football pay for itself” and never be a drain on the university funds.

- Playing by the rules while insisting on graduation, integrity and abiding by the rules to prevent “the tail from wagging the football dog.” He ended freshman eligibility and did away with the “tramp athlete” who moved from school to school as basically hired football mercenaries for their skills.

The first item on the docket was upgrading the football schedule — provided it came with sound business practice to complement it.

Because it was getting blackballed by the other Midwest powers, the Notre Dame football schedules become extremely unattractive and, hence, unprofitable. The eight-game slate in 1912 included regional small schools such as St. Viator, Adrian, Morris Harvey, Wabash and Marquette.

One of Harper’s first moves was to write to the United States Military Academy in West Point, NY., for a game. Army originally offered Notre Dame $600 for travel expenses, but Harper was able to haggle for $1,000.

With penny-pinching practices such as taking 14 cleats for the 18-man Notre Dame team on the railroad trip, plus packing their own meals from the student-dining hall, the trip ended up costing $917 — an $83 profit.

It might be peanuts in 2013, or at least the cost of a Notre Dame home game ticket, but it was striking gold in 1913.

In a span of 27 days in November, Notre Dame pulled watershed road upsets against Army (35-13), Penn State (14-7), Christian Brothers in St. Louis (20-7) and Texas in Austin (on Thanksgiving Day) for a remarkable 7-0-debut campaign. As a coach, Harper proved to be an innovator with a passing attack at Army that awed the eastern media and aided Notre Dame’s place on the football map.

Soon, other eastern powers such as Yale and Syracuse were added to the schedule, and a $6,000 guarantee to play at Nebraska five years in a row from 1916-20 was achieved to help build Notre Dame’s financial coffers.

Just as important, Harper was an ambassador who prioritized what he termed “mending the Big Ten fences.” He visited the programs at Purdue, Northwestern and especially his alma mater, Chicago, where Stagg mentored him on scheduling matters (although the Maroons and Notre Dame would never meet during that time).

By 1917, the University of Wisconsin was on Notre Dame’s schedule, and future games were on the docket with Purdue, Indiana and Northwestern.

Michigan State, which would not join the Big Ten until the 1950s, also became a popular regional opponent. In fact, in 1917 the Spartans offered Harper’s assistant, Rockne, their head coaching job, and Rockne was set to depart to East Lansing — until Harper persuaded him to stay because he would be succeeding him soon.

In his five seasons at Notre Dame from 1913-17, Harper’s team played only 16 games at home and 24 on the road. Yet not only did he compile the 34-5-1 record, but he indeed had generated the economics to make football a profitable venture at the school.

Rockne would learn well from his mentor in the ensuing years, and he would always credit Harper for laying the foundation to his system.

Notre Dame: Act II

Harper stepped down from his Notre Dame post in 1918 and returned to his family’s cattle business, now located in western Kansas. There, oil also would be discovered on his 20,000-acre ranch.

To Harper’s delight, Rockne elevated Notre Dame into “America’s Team” in the 1920s while compiling a 105-12-5 record, achieving five unbeaten seasons and capturing consensus national titles in 1924, 1929 and 1930.

After Rockne’s March 31, 1931 death in a plane crash about 100 miles from Harper’s ranch, tumult returned to the Notre Dame athletic department, and former school president Rev. Matthew Walsh C.S.C., called his old friend Harper to return to the school as the athletics director and help put the department’s house back in order.

Prior to Harper’s arrival, assistant coaches Hunk Anderson and Jack Chevigny were named “senior coach” and “junior coach,” respectively, and it was an arrangement that led the program to become the “In-Fighting Irish.” Chevigny, who would die serving in World War II, departed the next season to be the head coach of the NFL’s Chicago Cardinals.

The “Great Depression” was another crisis for the athletic department, especially because the newly built Notre Dame Stadium was far too large (its capacity was 50,731 at the time) for such a small school. Notre Dame’s eight home games in 1932-33 averaged only 17,625 paying customers.

Grants-in-aid were cut in half, and the recruiting budget was basically limited to postage stamps for letters to be sent out to prospects. This frugality by Harper drew the ire of Anderson, who would be fired after a 3-5-1 season in 1933.

Harper also persuaded the school leaders to enforce the rule that a 77 average was the minimum requirement for a student to partake in athletics.

The football house was back in order when Harper returned to his ranch in 1934, allowing former Four Horseman Elmer Layden to take over as the athletics director and head football coach.

The Ultimate Sportsman

When Harper died on July 31, 1961 at age 77, Notre Dame sent its revered athletics director Ed “Moose” Krause and business manager Herb Jones to Kansas as representative to pay respects.

The Fighting Irish football program had experienced its shares of domination and defeat from 1913-60, including the 2-8 campaign in 1960. Krause was born the same year (1913) that Harper had first come to Notre Dame, but over the years the two had forged a strong friendship with their common bond.

The anomaly in Harper was that even though he was recognized as an impeccable man of integrity, organized religion was not part of his fabric, and he requested no formal funeral service or eulogy at his burial.

“His whole religion was geared around the Golden Rule,” noted his son, James of the “do unto others as you would want them to do unto you” principle.

At the gravesite, just as Harper’s coffin was to be lowered into the earth, his widow, Melville, stepped forward to make a request.

“As most of you know, Jesse was not a man of religion,” she began. “He didn’t want any formal funeral service, but in his lifetime he dearly loved a very religious school, Notre Dame, where we twice spent some enjoyable years … Even though Jesse may not have wanted it, I would ask Mister Krause if he would say a few words.

With a gentle demeanor that belied his huge frame that earned him the “Moose” moniker, Krause briefly touched on Notre Dame’s deep appreciation for Harper’s work before ad-libbing and reciting “A Sportsman’s Prayer,” whose author is anonymous:

“Let me live, O Might Master, such a life as men should know,

“Testing triumph and disaster, joy and not too much of woe.

“Let me run the gamut over, let me fight and love and laugh,

“And when I’m beneath the cover, let this be my epitaph:

“Here lies one who took his chances in this busy world of men,

“Battled fate and circumstances, fought and fell, and fought again.

“Won some times but did no crowing, lost some time, but did not wail,

“Took his beating but kept on going, and never let his courage fail.

“He was fallible and human, therefore loved and understood

“Both his fellow men and women, whether good or not so good.

“Kept his spirit undiminished, never laid down on a friend.

“Played the game `til it was finished, lived a Sportsman to the End.”

Ten years later, in 1971, Harper was enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame. It was a well-deserved honor for the man who helped set Notre Dame on its path to glory.

The Gift Of Prophecy

There is often talk about the pressure-cooker that is the Notre Dame job as the head football coach.

Hall-of-Fame coaches such as Frank Leahy (1941-43, 1946-53), Ara Parseghian (1964-74) and Lou Holtz (1986-96) each lasted only 11 years apiece, while Dan Devine (1975-80) managed six years before stepping down.

However, this is hardly a “modern day” occurrence. Jesse Harper turned the coaching reins over to his assistant, Knute Rockne, in 1918 for a couple of reasons. One was to get back into his family’s cattle business in Kansas. One of Jesse’s sons, James Harper, recounted the second reason many years later that has been published.

“When I told my father that I’d like to be coach myself, he said: `Sit down right now and we’re going to have a man-to-man talk, and I’m going to tell you why I left Notre Dame. It wasn’t because of the school or anything else; I had a marvelous relationship, but I could see the handwriting on the wall. I could see the pressure by the alumni to do nothing but win, win, win, regardless of what you did to the boy, the school or anything else.

“Football is to build men and to build good sportsmanship. That’s why I left. You do not have any easy games. Every team that plays you is up. Every team that beats Notre Dame has a successful season.

“It’s just a crazy, marvelous sport, the finest sport we have. It does more to develop character in men for future life than any sport we have. But I had to leave Notre Dame because winning was getting too important there.”

Much has changed since Harper left coaching in 1918. Expectations at Notre Dame have not.

— By Lou Somogyi, Blue & Gold Illustrated