Sept. 4, 2015

By Craig Chval Sr.

Only two University of Texas head coaches have led the Longhorns to victory over the University of Notre Dame in the 10 games played between the two schools in a series that dates back to 1913 – and they named the football stadium after one of them.

But with all due respect to Darrell Royal, the late Texas Hall of Fame head coach whose name Longhorns’ stadium bears, Jack Chevigny, the only other UT head coach to defeat Notre Dame, may have led an even more remarkable life.

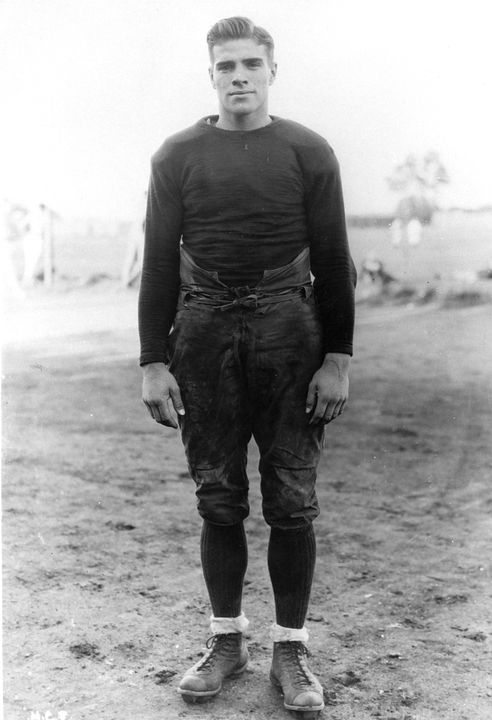

Chevigny died in combat at Iwo Jima, Japan on February 19, 1945, and his death reflected the way he lived his life – embracing the toughest challenges. From his days as an undersized star on Knute Rockne’s Fighting Irish teams to the Texas rookie head coach who got his players to believe they could pull off a colossal upset of his alma mater, to the successful lawyer and businessman who wouldn’t take no for an answer when an old football injury disqualified him from enrolling in the military during World War II, Chevigny lived life with a relentless and unflinching courage.

Born in Dyer, Indiana, Chevigny was the president of his graduating class at Hammond High School in 1924 before enrolling at Notre Dame, where he intended to follow in the career footsteps of his father, a physician. While Chevigny decided at Notre Dame that he might not be cut out for the medical profession, there was no question that he was just what Rockne was looking for in a football player.

As Rockne demanded of his best players, Chevigny was a terror carrying the ball, blocking for his teammates and on defense. Sportswriter Grantland Rice, who had earlier immortalized Notre Dame’s Four Horsemen, claimed that Chevigny had made the greatest tackle he had ever seen, preserving Notre Dame’s 1927 7-7 tie against Minnesota with a diving goal-line stop of the Gophers’ All-American fullback Herb Joestling.

The following season, Notre Dame brought a 6-2 record, mediocre by Rockne’s standards, into its game with undefeated Army. Few experts gave the Irish a chance to avenge their 18-0 loss to Army the previous season, and Rockne seemingly agreed, concluding that this was the perfect opportunity to deliver what has become arguably the most famous locker room speech in history.

At halftime of a scoreless battle in Yankee Stadium (although some accounts insist that the speech occurred before the game – there is practically a cottage industry devoted to attempting to distinguish fact from fable of Rockne’s speech), Rockne told his troops the story of Notre Dame All-American George Gipp’s deathbed request that Rockne someday ask one of his teams facing Army to “give it all they’ve got and win one for the Gipper.”

While many details of Gipp’s dying words and Rockne’s subsequent reference to them have been debated since Ronald Reagan (Gipp) and Pat O’Brien (Rockne) portrayed them in the 1940 film, Knute Rockne, All-American, some details are unquestioned. One is that with the Irish trailing Army 6-0 in the fourth quarter, Chevigny blasted into the end zone on fourth-and-goal from the Army one-yard-line to tie the score. There seems to be no serious dispute that Chevigny called out, “That’s one for the Gipper,” although accounts differ as to whether that occurred as Chevigny crossed the goal line or as he reached Rockne along the Notre Dame sideline.

As time wound down in the deadlocked struggle, Chevigny did all he could to ensure that Notre Dame delivered on Gipp’s request – after all, Gipp didn’t implore Rockne to have the Irish “tie one for the Gipper.” With Chevigny getting the bulk of the carries against the tenacious Cadet defense, the Irish reached Army’s 16-yard-line. Some accounts had Chevigny knocked out cold while making a tackle at some point after he scored the tying touchdown; others had Rockne taking him out due to injury and exhaustion just before Irish quarterback John Niemic threw a 32-yard touchdown pass to Johnny “One-Play” O’Brien on fourth down to give Notre Dame the upset victory and provide Reagan with a future political slogan.

Rockne called Chevigny one of the toughest players he ever coached, and proved that he wasn’t simply throwing out empty platitudes by adding Chevigny to his coaching staff upon graduation. Chevigny spent two seasons coaching the running backs, helping the Irish to undefeated national championship seasons in both 1929 and 1930. Upon Rockne’s tragic death in March, 1931, Chevigny was named Notre Dame’s “junior coach,” working alongside “senior coach” Hunk Anderson for one season while finishing his juris doctorate degree at Notre Dame’s Law School.

Chevigny spent two seasons as the head coach of the NFL’s Chicago Cardinals before taking the head coaching position at St. Edward’s University in Austin, Texas. In his lone season at St. Edward’s, which was founded by Notre Dame founder Fr. Edward Sorin, Chevigny’s squad won the Texas Conference Championship.

That season was enough to capture the attention of the University of Texas, which hired Chevigny as its head coach and athletic director in 1934. As fate would have it, Texas’ second game during Chevigny’s rookie season was on the road against Notre Dame.

Not only did the new coach promise his new players – coming off a 4-5-2 season – that they would defeat Notre Dame (even though the Irish had lost fewer combined games over the past two seasons than Texas had lost in 1933), but he provided a detailed blueprint as to exactly how they would accomplish the upset.

During the week leading up to the Notre Dame game, Chevigny sought to exploit a tendency for fumbles by Notre Dame’s return team. He had his kicker practice kicking to a specific spot, instructing his best tackler to be prepared to separate the return man from the ball with a jarring tackle. Chevigny promised his men that the resulting touchdown and conversion would be enough to win the game.

It happened just like Chevigny had promised – and his players had practiced. The Longhorns forced a fumble on the opening kickoff, converted the turnover into a touchdown, and made it stand up for a stunning 7-6 upset victory. It was Notre Dame’s first loss in a home opener in 38 years.

In an article that appeared in The Washington Star on January 2, 1978, the day Notre Dame would go on to upset number-one Texas in the Cotton Bowl to claim the national championship, former Notre Dame director of public information John V. Hinkel wrote that Chevigny greeted Notre Dame head coach Elmer Layden after the game with tears in his eyes, proud of the accomplishment of his Longhorn players, but hating that it came at the expense of his alma mater and his great friend Layden.

Chevigny’s first Texas team went 7-2-1, but his next two teams managed a combined six wins, and he resigned to become an assistant attorney general for the State of Texas. Chevigny also built a successful oil business. When World War II broke out, he was determined to serve in the military.

After being rejected numerous times due to a football knee injury, Chevigny finally was allowed to enlist in the U.S. Army. But after a few months, Chevigny got what he really wanted – he received a commission as a first lieutenant with the Marines.

The Marines made the most of Chevigny’s fame and matinee-idol looks, using him in publicity events and shoots. They also installed him as the head coach of their football team at Camp Lejeune, which was 0-2 before Chevigny took the reins. Under Chevigny, the squad, which often played before crowds of 15,000, won six of seven games, tying the seventh.

Chevigny’s success coaching football and his role as a physical training instructor at Camp Lejeune didn’t allow him to make the contribution that he longed to make. So Chevigny sought and received a transfer to a combat role in the Pacific theater.

According to Jeff Walker, author of The Last Chalkline: The Life and Times of Jack Chevigny (published by Wasteland Press in 2012 and available through Amazon), Chevigny told his brother Jules that, “He had to be there with the boys.”

Chevigny landed on Iwo Jima on the very first day of the five-week battle, which ultimately provided a critical U.S. victory against Japanese forces. The Japanese position was heavily fortified, costing 6,800 American lives, including Chevigny’s, who was killed within hours of landing on the beach.

To the end, and just as he intended, Chevigny was there for his boys.