Oct. 27, 2016

By Lisa Mushett

The composite resume quite likely qualifies as the most impressive of anyone ever to play football at the University of Notre Dame:

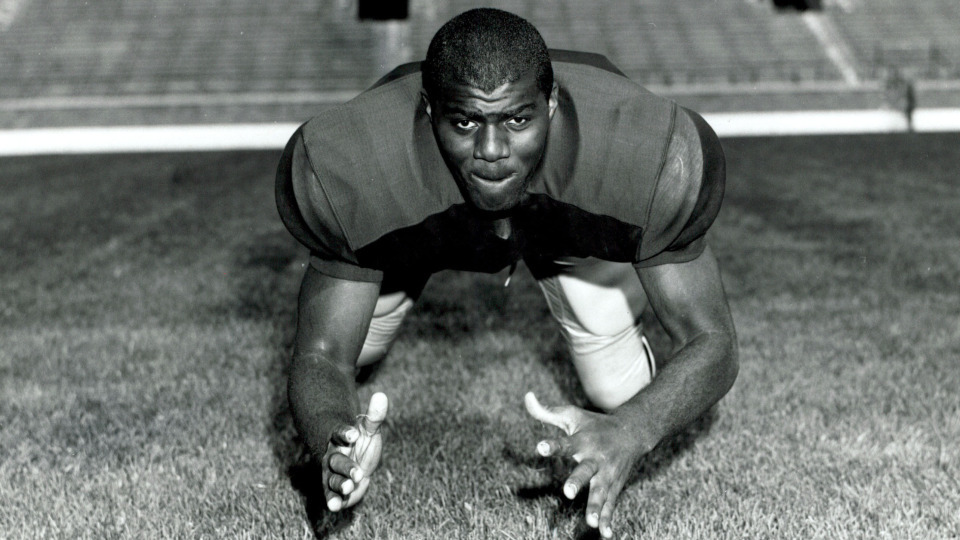

–Consensus All-America selection as defensive end

–Member of national championship team in 1966

–Academic All-American who later was inducted into the Academic All-America Hall of Fame and received the 2001 Dick Enberg Award given annually to a person whose actions and commitment have furthered the meaning and reach of the Academic All-America program

–Graduate with a political science degree in 1967

–First-round National Football League draft pick in 1967

–15-year NFL career with the Minnesota Vikings and Chicago Bears

–NFL champion with the Vikings in 1969 and a four-time Super Bowl participant (1969, 1973, 1974, 1976)

–Nine-time Pro Bowl selection in 1969-77

–Six-time first team All-Pro in 1969-71 and 1973-75

–NFC Defensive Player of the Year in 1970 and 1971

–NFL MVP in 1971

–Graduate of University of Minnesota Law School in 1978

–Pro Football Hall of Fame inductee in 1988

–NCAA Silver Anniversary Award winner in 1992

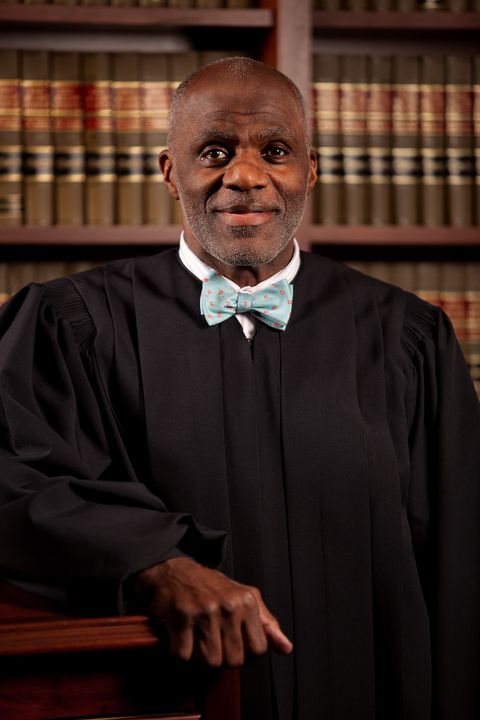

–Minnesota Supreme Court Justice from 1992 through 2015

–College Football Hall of Fame inductee in 1993

–Recipient of the NCAA Theodore Roosevelt Award, the highest award presented by the NCAA to a former student-athlete, in 2004

—National Football Foundation Distinguished American Award winner in 2005

The name on the top of that resume is Alan Cedric Page.

The list of accomplishments grew by one this weekend as Page became the latest winner of the Notre Dame Monogram Club’s Moose Krause Distinguished Service Award.

It’s the highest honored bestowed by the prestigious group of former Irish letter-winners–recognizing a former monogram winner who has achieved notoriety with exemplary performance in local, state or national government, has shown outstanding dedication to the spirit and ideals of Notre Dame, demonstrated responsibility to and concern for their respective communities and has displayed an extraordinary commitment and involvement with youth.

Page joins a select list of past award recipients including the late University President Emeritus Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C (1986), Page’s former football coach Ara Parseghian (1998), President Emeritus Rev. Edward A. “Monk” Malloy (2005), NFL Hall of Famer Jerome Bettis (2007), former Indiana Gov. Joe Kernan (2012) and former WNBA great and current San Antonio Stars general manager Ruth Riley (2015).

“There is no one more deserving of the Moose Krause Award than Justice Page,” Monogram Club president Kevin O’Connor says. “His exemplary career in public service as a distinguished justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court, combined with his long-standing commitment to the education of students in his community, makes Justice Page an ideal choice for this award.”

Page’s humble beginnings saw him grow up in the blue collar mill town of Canton, Ohio. He became the only black player on either his high school or college football team during a time of great racial tension in the country. His outstanding football career led to those All-America and NFL Hall of Fame honors.

Page earned his law degree while playing in the NFL and became the first African-American to hold a major elected office in Minnesota. He and his wife, Diane, more than 30 years ago started the Page Education Foundation which has afforded postsecondary educational and mentoring opportunities to more than 6,500 youths in Minnesota.

With a lifetime of accomplishments that robust, it is only fitting the 71-year-old Page, who lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota, is being recognized by his alma mater this weekend.

The Beginning

Born August 7, 1945, in Canton, Ohio, Alan was the youngest of four children of Howard Sr. and Georgianna Page. Many people in town worked at the local steel mills, and few dreamed of attending college. The Page family lived in a modest home on the southeast side of town. Alan would never say they were poor, only that “times were tough.” Howard Sr. owned a record shop and brought musical acts to the area, but his primary line of work was at a local bar called Main Event, which housed a gambling parlor in the back. After the local mill workers were paid each week, Howard Sr. was often gone days at a time, manning the gambling parlor, leaving Georgianna tending to life on the home front and working a number of odd jobs to help make ends meet.

Page’s parents constantly stressed the importance of education from as early as Alan can remember. Although both were high school graduates, the Pages were never afforded the opportunity to attend college and vowed things would be different for their children.

“Both my mom and dad were very intelligent and understood that education was a tool one could use to overcome the discrimination that comes along with being a person of color,” Page recalls. “They knew having an education would put you in a position to control your own destiny and not have to rely on anyone else.”

The family moved to the east side of Canton, which boasted a stronger school system, when Page was 9. His mother and father eventually sent the Page children to Canton’s Central Catholic High School.

Georgianna passed away when Alan was 13. In the book “All Rise: The Remarkable Journey of Alan Page” written by longtime friend Bill McGrane, Page talks about the death of his mother and the impact it still had on him almost 50 years later.

“I was devastated,” Page said. “The getting over it is more of an evolution than anything I ever did. There isn’t a day I don’t think about my mother. I still feel the hurt of losing her.”

Alan was about to start his freshman year in high school at Central Catholic when his mother died. His older brother Howard was a sophomore there while his older sisters were enrolled in college.

Central Catholic, located 15 miles from the Page home, seemed like it was another world to Alan as he was not Catholic (although he would convert his junior year) and was one of only a handful of black students at the school. Page kept to himself, attending class and playing tuba in the school band. Searching for anything to ease the pain of losing his mother, Page tried sports. Tall and initially awkward, Page attempted playing basketball, but he wasn’t very good. Baseball was too boring–and football was never even a thought until he saw how much Howard enjoyed playing the game and decided to give it a try.

As a junior, Page–now standing over 6-4 and weighing more than 200 pounds–became a star in football. Soon, major college football powers were coming to Canton to see what all the fuss was about, including then-Irish assistant coach Hugh Devore, who later became the interim head coach in 1963.

“I was pretty familiar with Notre Dame–both on and off the field–because of Central Catholic,” says Page, who was also considering Michigan State and Purdue. “In terms of the name and history, Notre Dame far exceeded the others. Football was a factor, but over time, the one thing that kept bringing me back to Notre Dame was the education. I kept thinking about what my dad had told me growing up, and my sense was academically, coupled with the strong alumni group nationwide, Notre Dame was the best choice.”

Under the Golden Dome

When Page arrived at Notre Dame in the fall of 1963, there was no shortage of tension in the world–including escalation of the Vietnam War and the expanding Civil Rights movement. Similar to Central Catholic, Page was one of only a handful of black students on the all-male campus. He struggled finding other students from similar socio-economic backgrounds and discovered quickly he had “never really learned how to learn” in the classroom. School was difficult and became a lot of work.

“It was tough for me,” Page says. “I had to grow up fast. On one hand, I was a football hero. On the other hand, I was not the wealthiest kid on campus, so having to live in that environment and get along was a challenge. I learned to compartmentalize things and keep an eye on what I was doing at the time. I became a loner, which didn’t solve my problems, but helped me get through it.”

The football field quickly became Page’s sanctuary. Initially he could only practice with the team, as NCAA rules in 1963 did not allow freshmen to play in games. And Notre Dame could have used Page, as it finished the year 2-7, resulting in the dismissal of Devore and the hiring of a new coach–Northwestern’s Ara Parseghian.

Parseghian, who had tried recruiting Page to Northwestern, immediately left a lasting impression on Page. During the first team meeting, the Hall of Fame coach broke football down into two aspects–field position and possession. It was that simple. If you could control field position and keep possession of the ball, you have a better chance to win. It was then the light came on for the struggling Page.

“As a high school football player, you are throwing your body around and you never really think about how the game works in harmony,” Page says. “After listening to Coach Parseghian that day, I realized I am not just throwing my body around, but there is an end result to all that we do on the field. It finally dawned on me that if you do the little things on the field, good things are going to happen. It was an aha moment.”

Page continued to reflect on Parseghian’s words from that first meeting, soon realizing those same basic football principles also applied to his daily life.

“Looking back on it now, it was just so obvious,” Page says. “If you do the little things in life that allow you to progress and move forward, good things will happen. When things are tough, the only thing you can do is keep pushing forward–control the field position–and keep working at it. Life can be very complicated, but there are some fundamental precepts that, if you follow, things will work out.”

“We knew Alan was struggling. There were not many black students on campus and not much of a social life for him,” Parseghian says. “It was very apparent from day one that he was a serious person and his goal was to use football to get an education. Alan was a person who absorbed the important things around him and knew what he wanted to do with his life. I guess he just needed to be reminded to focus on the fundamentals.”

In the three years Page was on the field, Notre Dame amassed a 25-4-1 record and was once again a national power. Page wrapped up his Notre Dame career as a consensus All-American and was instrumental in the Irish winning their seventh national championship his senior season. He graduated the following spring with a degree in political science and was drafted as the 15th pick in the first round of the NFL Draft by the Minnesota Vikings.

Page enjoyed a 15-year NFL career with both Minnesota and the Chicago Bears, leading the Vikings to four Super Bowls and becoming the first defensive player to earn the NFL Most Valuable Player Award in 1971. A member of the famed “Purple People Eaters,” he played in 218 consecutive games, tallied 173 career sacks and blocked 28 kicks in his illustrious career. He was also the Vikings player representative on the NFL Players Association for eight years and served on the executive committee from 1972-75, in what was a prelude to life after football for Page.

Legal Eagle

Page, who grew up watching endless episodes of Perry Mason on television, was fascinated by the law and eventually knew he was destined for something in the legal profession. He always had an interest in social studies, civics and government. The 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown vs. Board of Education ultimately touched Page in ways he never could have imagined. That landmark decision declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students unconstitutional.

“I have always had this sense of wanting things to be fair,” Page says. “I suppose it comes from being a black kid in the 1950s and knowing things weren’t fair even at 8 years old. When you grow up in a climate of discrimination, you are always conscious of it, even though you are not focused on it. Brown vs. Board of Education was the first steps in Equal Justice Under Law. To me, those words are magic.”

Page started laying the groundwork for his future by earning his juris doctorate from the University of Minnesota in 1978 while still playing for the Vikings. After retiring from the league in 1981, Page worked as a lawyer, eventually joining the staff of Minnesota attorney general Hubert H. Humphrey III. Page soon become assistant attorney general.

Page’s goal was to eventually join the Minnesota Supreme Court, and he was elected an associate justice of the court in 1992, becoming the first African–American in history to hold a state-wide office in Minnesota. He, and his signature bow ties, were re-elected to the court in 1998, receiving the most votes by a political candidate in state history, and then again in 2004 and 2010. Page retired from his Supreme Court seat in 2015 (Minnesota enforces a mandatory retirement for judges at the end of the month they turn 70). If he had his choice, he would still be serving today.

Giving Back–The Page Education Foundation

Perhaps the most fulfilling achievement for Page has been the success of the Page Education Foundation. Throughout his life, Page had passed on the message his mother and father instilled in him at a young age regarding the importance of education. Page has always looked for ways to promote his message of equity and fairness to the next generation.

In 1988 Page learned he was being inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. At that same time, Alan and Diane founded the Page Education Foundation which provides financial and mentor assistance for local students of color to attend public and private universities, colleges and trade schools in Minnesota. What started as a dream of raising $100,000 to give 10 young people postsecondary opportunities, has now garnered over $14 million and sent almost 6,500 students to Minnesota schools and another 40 to Notre Dame (the one exception to the Minnesota rule) over the past 30 years. Not only do the students receive financial assistance, but they also are required to perform at least 50 hours of community service each year, delivering Page’s missive on education. Over the years, Page Scholars have volunteered more than 420,000 hours.

“We are pretty proud of the Page Education Foundation and all of the Page Scholars,” Page says. “Each one, in his or her own way, is changing the world. As Martin Luther King Jr. said, `There is nothing more dangerous than to build a society with a large segment of people in that society who feel that they have no stake in it; who feel that they have nothing to lose. People who have stake in their society protect that society.’ We are creating that hope.”

More Work to Be Done

As Page returns to campus this weekend, he will have in tow his most prized possession–his family–including his wife of 43 years, four children, including daughter Kamie who played soccer at Notre Dame for two years, and four grandchildren. He looks forward to showing them his former dorm rooms in Badin and Fisher Halls, as well as the hallowed grounds of Notre Dame Stadium where he wreaked havoc on opponents for three years.

But once the weekend is complete, there will be no rest for the man who has run 10 marathons in his lifetime and still insists on running “only three miles a day.”

“I have had a lot of good fortune in my life,” Page says. “The football, the law, the Page Foundation is all good, but I continue looking forward and not back. What’s done is done, and what hasn’t been done still needs to be done. I still have a lot of work left to do.”

Lisa Mushett, a former Notre Dame associate sports information director, now serves as director of marketing and communications for the United States Tennis Association Northern in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area. She is a University of Texas graduate and earned a master’s degree from the University of Illinois.