Sept. 26, 2013

By Lou Somogyi, Blue & Gold Illustrated

Notre Dame’s 2012 football season began with a trip across the Atlantic Ocean to Ireland and concluded with an excursion to Miami for a shot at the national title.

In between, a host of other trips included traveling from one coast out in Boston (Boston College) to the other in Los Angeles (USC) just two weeks later. For good measure, there also was a journey to a place somewhat right in between, at Norman, Okla., to play the Oklahoma Sooners.

Other than the trip overseas, the Notre Dame team would leave Friday afternoon, arrive within a few hours, sleep comfortably in hotels with all arrangements made and a full staff of team managers and administrators in tow, play the follow evening and be home in the wee hours of Sunday morning.

Nearly a century earlier, when Notre Dame’s national scheduling took root under athletics director and football/basketball/baseball head coach Jesse Harper, it was a different world.

Up until the 1913 season, the small, Catholic school in the Midwest had never sojourned farther for a football game than the 415 railroad miles to play Pittsburgh.

That all changed in November 1913, when in a span of four weeks the Notre Dame football team logged more than 5,000 railroad miles while traveling to West Point and Penn State out East — in a span of six days — and later to St. Louis before heading to Austin, Texas.

AN OPPORTUNITY OPENED

The 29-year-old Harper’s goal and mandate when he took the Notre Dame job late in 1912 was to make “football pay for itself” while finding teams across the country willing to play it and open up its checkbooks.

At the time, Notre Dame was in the midst of a scheduling crisis. Its upset of Michigan in 1909 made the “Catholics” — the team’s nickname back then — more shunned by the Western Conference (Big Ten) members, a union that formed in 1896. It wouldn’t be until 1917 that Harper’s tact, diplomacy and persistence allowed him to break the Big Ten ice and add the University of Wisconsin to the schedule, followed by Purdue (1918) and eventually Indiana and Northwestern (1920).

Prior to that, though, Harper had no choice during his tenure from 1913-17 but to reach out elsewhere to find games — while at the same time keeping Notre Dame’s accounting ledger books in the black. Among his coups was securing a $6,000 guarantee to play at Nebraska six years in a row from 1915-20 (the Cornhuskers wouldn’t visit Notre Dame until 1921). Home-and- home series’ were not an option financially for Notre Dame back then, but these road shows had to be done to help grow the school’s financial coffers.

In essence, Notre Dame was somewhat like a fledgling program a la Boise State 15 years ago, or just as recent Football Bowl Subdivision additions South Florida or Connecticut — both of whom won at Notre Dame in the last five seasons. They too had to earn a reputation for themselves before joining the big leagues. Only Notre Dame elevated it to a much higher tier starting in 1913.

Other marquee games that Harper secured at this time included trips to Yale and Syracuse in 1914, and continued trips to Army, plus another one to Texas in 1915.

In one of his first major acts as the school’s athletics director, Harper initiated contact with Army’s football manager, Harold Loomis, in a Dec. 18, 1912 letter to schedule a football game, according to Murray Sperber, author of the 1993 book Shake Down The Thunder: The Creation of Notre Dame Football.

At the time, it was akin to the class nerd asking the head cheerleader to the prom. Army was one of the football blue bloods from the East, where the sport was born, and seldom played anyone outside its region. Notre Dame was ambitious in its growth, but lacked a reputation of prowess beyond its regional area.

Fortunately, in this case, the timing was ideal for a meeting. After the 1912 season, superpower Yale, which had annually played Army since 1893, cancelled its 20-year series with the West Point brass because the Cadets were using what they considered unfair eligibility tactics. (It didn’t help that Army also beat Yale in 1910 and 1911.)

Army had been recruiting players who had completed undergraduate playing careers at other schools, and then enlisted them to play four more years for the Cadets while in training, thereby breaking the spirit of the rules pertaining to college eligibility. An example Sperber pointed to was Elmer Oliphant, an All-American at Purdue in 1912 and 1913 who would graduate in 1914 — and then play four more years at Army from 1914-17.

That was just one of the reasons why a Notre Dame-Army game was perceived as a mismatch, or a latter-day version of David and Goliath.

Thus, Army suddenly had a Nov. 1, 1913 date open, and Harper was not fazed about the Cadets’ eligibility practices, even though he was a stickler for following the rules.

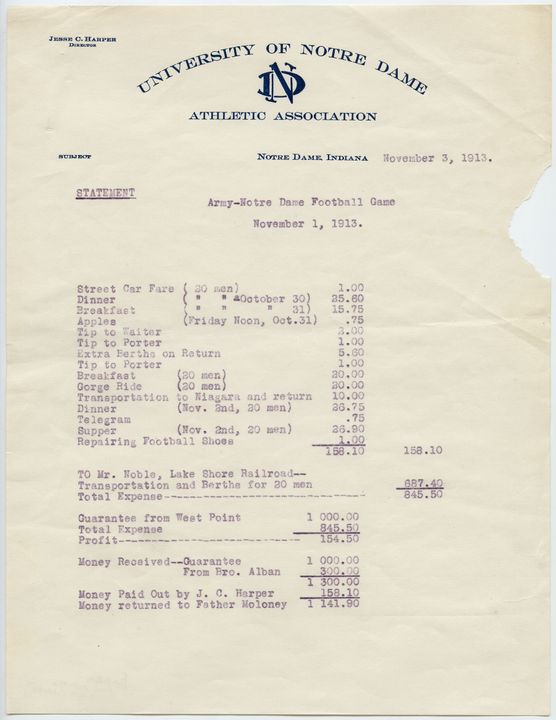

However, there was a caveat. Loomis offered Harper $600 for travel expenses to West Point. However, Harper calculated that even taking frugality to its limit, Notre Dame would need $1,000 to cover expenses.

Initially reluctant to haggle, Loomis eventually agreed to the deal.

`THERE WAS NO PAMPERING IN THOSE DAYS’

On Thursday, October 30, two days before the showdown, Harper and 19 players embarked on their overnight, 24-hour train ride that would cover 875 miles. To save on expenses, the nuns in the school’s dining hall packed sandwiches for the players to take on the trip.

Frugality was even involved with how much equipment the team had. There were only 14 pair of football cleats for the 19 players, meaning it had to be resourceful with substitutions and correct shoe sizes for everyone. Having “dual-purpose” shoes helped.

In the 2007 book Notre Dame And The Game That Changed Football author Frank Maggio in his research discovered a quote about the trip from Notre Dame starting end Fred “Gus” Gushurst, who played the side opposite senior captain Knute Rockne: “We would wear our shoes without cleats, of course, while on the train and then, just before game time, screw the cleats into the soles of the shoes.”

Student managers or porters also need not apply. Each player carried his own gear and equipment.

“We were permitted few luxuries on this trip from Indiana,” recalled Harper years later. “The boys carried their uniforms in satchels — some wearing their jerseys under their coats to conserve space.”

The trip remained with Rockne the rest of his life.

“The morning we left for West Point, the entire student body of the university got up long before breakfast to see us to the day coach that carried the squad to Buffalo — a dreary, all-day trip,” he would note in his future years. “From Buffalo we enjoyed the luxury of sleeping-car accommodations — regulars in lowers, substitutes in uppers. There was no pampering in those days. We wanted none of it.

“Our only extra equipment was a roll of tape, a jug of liniment and a bottle of iodine. To cut expenses, we traveled by coach as far as Buffalo before changing to sleepers.”

Army’s team mascot Willet J. Baird — who later became a high-ranking officer with the military — was the welcoming committee when Notre Dame finally arrived at West Point on Friday, Oct. 31 around 1:30 p.m. He was struck by how extremely light it traveled compared to the eastern powers they had faced, and how the players were more in awe of the sites at the academy.

“I was in the Cadet locker room on a Thursday afternoon following practice when I first heard of the Indiana institution called Notre Dame,” said Baird, quoted in the 1975 book Wake Up The Echoes authored by Ken Rappoport. “The players, as usual, were asking questions about this Indiana team and no one present seemed to know a great deal about it. Everyone, however, was convinced that Saturday would bring a `breather.’ “

For the Notre Dame players, it was like the first day of arriving in the major leagues — “The Show” — after years of toiling in the minors.

“Most of the players visiting the playing field expressed no end of amazement and joy over the fact that the field itself was very smooth, well marked, and resembled the appearance of a well-kept lawn,” Baird said. “This to them was most remarkable.”

Meanwhile, many of the Notre Dame players wondered whether it would be possible to obtain some ankle wraps, knee guards, supporters, shoestrings and even two extra pairs of football pants. Most graciously, Army and a local storekeeper supplied them to the rag-tag group.

“They presented the usual appearance of a small college team which considered itself lucky to have so many players,” Baird said.

They received a special treat when the Cadets entertained and fed the visitors at the academy’s mess hall, prior to Notre Dame engaging in a light workout.

Rockne offered a dime to Baird for a large adhesive roll, but he was given it gratis. Meanwhile, Harper was mortified when he saw the footballs used at Army compared to the ones Notre Dame brought along.

“After playing the game, Jesse could stand it no longer and requested that the Army show him and some of the Notre Dame boys how to lace a football; for as Jesse said, they could not do a good job of this at Notre Dame,” Baird recalled.

Notre Dame might not have known how to properly lace a football, but it provided an education on how to play with it.

It stunned the Cadets with a 35-13 victory and swept the rest of its road contests that month to finish 7-0. The tight 14-13 contest in the first half was blown open in the second half with the passing combination of quarterback Gus Dorais and end Rockne that stunned the Army team, while fullback Ray Eichenlaub, who would also be named an All-American, provided a running complement.

Reportedly, the trip even netted a profit of anywhere from $83 to $154.50, as reported by Maggio, thanks to room and board offered at West Point.

It was a travel party 100 years ago that to this day resonates at the school and in college football.

THE GROWTH OF A MEMORABLE SERIES

For all the pomp and circumstance that surrounds the Nov. 1, 1913 Notre Dame-Army game in its centennial year, there were approximately only 3,000 spectators in attendance at Cullum Hall Field for the game.

Oh, and they all got in free.

A rematch was scheduled the next year, which Army won, 20-7, this time in front of a larger, more enthusiastic crowd of 5,500. Something special was brewing, and the two teams continued to meet — and would annually through 1947.

In a 1957 interview with sportswriter John M. Ross, Notre Dame 1913-17 head coach Jesse Harper recalled the following:

“Because of this ringing success in our Eastern debut, Army immediately became the big game on Notre Dame’s schedule. And the Cadets, thirsting for revenge, awaited each succeeding game eagerly. And so the rivalry blossomed.

“In 1918, when I turned over the coaching reins to Knute Rockne, I told him: `Rock, keep this Army game on your schedule. One day it might be big enough to play in New York City.’ “

By 1923, the game was played in front of a capacity audience of 30,000 at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field.

In 1924, the game shifted to the Polo Grounds, where a capacity crowd of 55,000 saw a 13-7 Notre Dame victory en route to their first consensus national title. It was also the day sportswriter Grantland Rice immortalized Notre Dame’s backfield as “The Four Horsemen.”

By 1925, the game became an annual meeting in hallowed Yankee Stadium, where a full 65,000 attended the first meeting there. The “One For The Gipper” victory over Army (12-6) occurred there in 1928, and in 1929 Notre Dame clinched another national title with a 7-0 victory versus Army in the season finale at Yankee Stadium in front of 79,408.

In the famous 1946 scoreless tie between No. 1 Army and No. 2 Notre Dame — the Irish would again win the national title at the end of the year — tickets were so in demand Notre Dame had to make $500,000 in ticket refunds. A $3.30 end zone seat was easily scalped for $200.

The days of getting in free were long over.

— ND —