Oct. 28, 2016

By Craig Chval Sr.

Flipping through the University of Notre Dame football archives, it would be easy to skip right past the 1986 season. The ’86 Irish finished with a 5-6 record, identical to their 1985 mark. To the casual observer, it would seem that 1986 was “same old same old.”

The reality was far different.

The 1985 Irish closed their 5-6 season with a 58-7 loss to Miami. The 1986 Irish closed their 5-6 season by overcoming a 17-point fourth-quarter deficit to defeat USC.

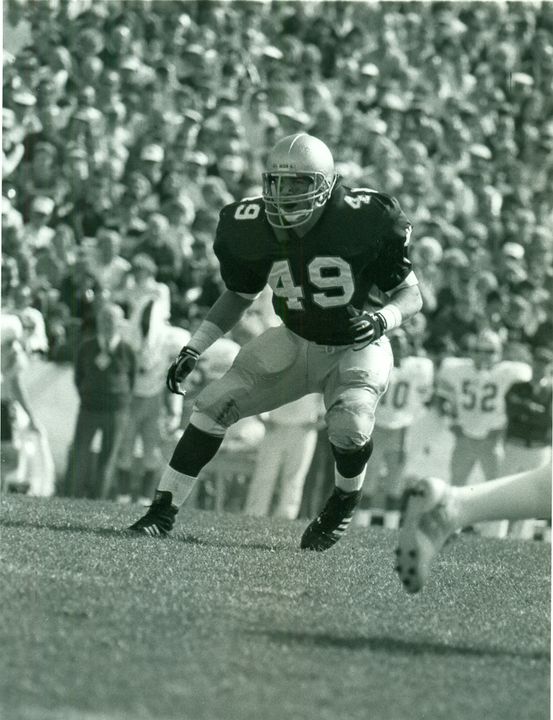

Gerry Faust resigned as Notre Dame head coach just days before he would lead the ’85 Irish against the fourth-ranked Hurricanes in the final game of his five-year tenure. Linebacker Mike Kovaleski, who would captain the 1986 Irish, sets the scene:

“The whole turnaround began the week we played Miami down in the Orange Bowl and got slaughtered,” he says.

“Everybody was kind of running scared. We all knew that we were not as prepared as we needed to be, and we knew that it likely wasn’t going to end well.”

Lou Holtz had been hired to replace Faust, and he was waiting for his new players when they arrived in South Bend.

Wes Pritchett, who would earn second-team All-America honors on Notre Dame’s 1988 national championship team and play for the NFL’s Atlanta Falcons, describes Holtz’s first meeting with his new players.

“He walked in on day one with a plan,” says Pritchett. “He took charge of everybody from the moment he walked into the first team meeting. And he never wavered from what he said.”

Kovaleski vividly recalls that first encounter with Holtz.

“The first thing he said was, ‘If you are interested in what I am interested in, and that’s winning a national championship, I want your eyes on me, your feet on the floor and your undivided attention. Otherwise, there’s the door.'”

Holtz implemented 6 a.m. offseason workouts, which still prompt a sigh of dread from Kovaleski. “Everybody knew they were going to end up throwing up their dinner from the night before.”

“He encouraged us to do stuff together,” Pritchett says. “He really pushed us to get to know each other because he knew that was important to winning.”

Flanker Milt Jackson, a fifth-year senior in ’86, saw the payoff of Holtz’s team-building efforts.

“We were a really close group,” he says. “We all loved each other and there were really no jealousies.”

Jackson credits those bonds among players with helping the ’86 Irish through adversity. But the true test would be on the field. And some questioned whether Holtz had undertaken an impossible task.

Writing in the Washington Post before the 1986 opener against No. 3 Michigan, Michael Wilbon opined, “This is no simple situation of a new coach trying to make things right again for a school’s football team. The magnitude of Lou Holtz’s mission at Notre Dame seems only a bit less significant than Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal.”

Notre Dame’s debut under Holtz provided both adversity and convincing proof that the Irish had the right man.

The Irish opened with a 75-yard touchdown drive and led 14-10 at halftime, before two Michigan touchdowns within six seconds in the third quarter put the Irish in a 24-14 hole.

The Wolverines escaped with a 24-23 victory thanks to a missed extra point, an endzone interception, a potential Notre Dame touchdown pass ruled out of bounds and a missed 45-yard field goal attempt with 13 seconds to play.

More adversity followed as the Irish lost five games by a combined 14 points, including a last-second loss to eventual national champion Penn State. The combined record of those five opponents was 43-15-1.

A 21-19 loss to LSU in Death Valley dropped the Irish to 4-6 and hit Kovaleski like a ton of bricks.

“I just lost it after that game,” he says.

“We had been in every game ââ’¬¦ we were right there ââ’¬¦ and we lost it. It was awful. How could we play this hard and keep losing?

“I took all of that personally, I tried to take it onto my shoulders as captain ââ’¬¦ how can I lead this team better and get us out of that rut?”

The rut only got deeper the next week in Los Angeles. Notre Dame fell behind USC 20-9 at halftime and trailed 30-12 late in the third quarter.

Kovaleski describes the mood on the Notre Dame sideline.

“We’re not done, this is our last game ââ’¬¦ we are NOT going out like this.”

But when USC scored a touchdown to take a 37-20 lead with 12:26 remaining in the game, it looked like that was exactly how the ’86 Irish were going out. Instead, Notre Dame used those final dozen minutes to earn a victory to close out the careers of those seniors, to launch a 1987 Heisman Trophy campaign for Tim Brown and provide a foundation for a 1988 national championship season.

“We were seniors and we didn’t want to go out like that,” says Jackson, who caught four passes for 111 yards against the Trojans. “All of a sudden we had a couple of big plays, and the next thing you know, we had the momentum.”

Jackson and quarterback Steve Beuerlein took just 43 seconds to provide some of that momentum. First, Beuerlein hit Jackson for 27 yards and then the tandem connected on a 42-yard touchdown pass. John Carney’s extra point after a Beuerlein-to-Jackson two-point conversion pass was nullified by penalty made the score 37-27.

A four-year starter for the Irish, Beuerlein enjoyed the best season of his Notre Dame career under Holtz, before becoming a Pro Bowl quarterback and playing 14 seasons in the NFL. But the Southern California native, with more than 200 family and friends watching his Notre Dame finale, nearly didn’t get the chance to rally the Irish.

Holtz had paid a visit to Beuerlein’s hotel room the night before the game, thanking his quarterback for his perseverance and leadership.

“It was a long talk and very emotional for me,” says Beuerlein. “It was one of the most meaningful conversations I ever had.

“And then, as he was leaving my room, he said, ‘As great as it’s been this year, if you throw an interception tomorrow, you’re coming out of the game.’

“I couldn’t believe he was saying that,” says Beuerlein. “I said, ‘You can’t tell me that the night before a game,’ and he said, ‘I just did.'”

Sure enough, after throwing 37 interceptions over his first three seasons, Beuerlein threw just his seventh interception of 1986 in the second quarter. Lou Brock Jr., turned it into a Trojan touchdown and Holtz turned to backup quarterback Terry Andrysiak.

“I thought my Notre Dame career was going to end that way,” says Beuerlein, a hint of disbelief seemingly still present in his voice.

“Then, on the first series of the second half, he came over to me and said, ‘Are you ready to play some football, son?’ and I said, ‘You will not regret this.'”

The Trojans had a chance to ice the game with 6:16 to play, with fourth and inches at the Notre Dame five. But Wally Kleine stuffed quarterback USC quarterback Rodney Peete for no gain, leaving the Trojan lead at 37-27.

A 49-yard Beuerlein-to-Brown pass set up Beuerlein’s fourth touchdown pass of the day, and another two-point conversion brought the Irish to within 37-35 with 4:24 to play (there was no overtime in college football at the time). After Notre Dame stopped the Trojans on three downs, Brown returned the ensuing punt 56 yards to the USC 16. On the game’s final play, Carney kicked a 19-yard field goal to give the Irish a 38-37 victory.

“Perseverance through adversity, that was the theme all year,” says Jackson.

“You find out a lot about yourself and you find out a lot about your teammates when you go through adversity like that,” says Beuerlein, who still holds the Carolina Panthers’ record for highest career completion percentage among quarterbacks with at least 500 attempts.

“We wanted to win so badly, we were so hungry for something to be proud of,” he says. “We all believed that if we just did what (Holtz) told us, eventually we’d be successful. He had this amazing way of making us believe him.

“That’s the legacy we learned and left.”

Kovaleski knew the Irish had finally gotten over the hump.

“We all said, ‘So this is how it feels. So this is what it’s like to play a game like this and win it.'”

“We never gave up because we were so close,” says Jackson.

The lessons weren’t lost on their younger teammates.

“I learned a lot from those guys,” says Pritchett. “They showed me how to work hard and be a leader when my time came.

“Winning becomes a habit, and you have to learn how to do that. We as a team did not understand what it took to win,” Pritchett says of the team’s mindset prior to the USC game.

The lesson took, apparently.

From 1987 through 1993 Holtz and the Irish went 71-11-1, with a national championship and two number-two final rankings. And the launching pad for all of that was when a 4-6 team decided it was going to finish 5-6 rather than 4-7.

Craig Chval is a former student assistant in the Notre Dame sports information department. A 1981 Notre Dame graduate, he now lives in Columbia, Missouri, and works as associate general counsel at Veterans United Home Loans (www.veteransunited.com).